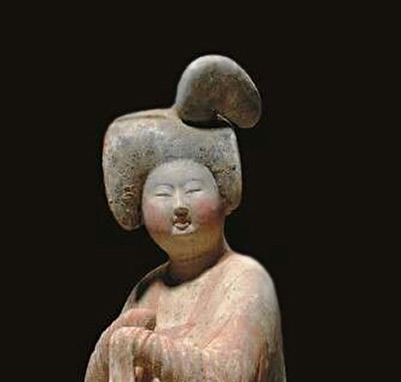

Tang Dynasty Terracotta Female Tomb Figurines, 8th c. (image in public domain)

Tang Dynasty Terracotta Female Tomb Figurines, 8th c. (image in public domain)

By Patrick Hunt –

Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) ceramics are otherwise deservedly famous for the sancai triple glaze, but often overlooked are the terracotta tomb attendant figurines of mingqi (“spirit deities”) who represent court ladies-in-waiting hovering nearby in the tombs to take care of the needs of the deceased from the latter half of the 8th century CE. While Ming and Qing porcelain often dominate modern aesthetic appreciation, the subtleties of the Tang Dynasty painted terracottas deserve far greater attention. This is also a Golden Age of Chinese Poetry – just think of the great poes Li Bai (701-62) and Du Fu (712-70) – after the brutal Sui Dynasty was supplanted by Li Yuan in Chang’an (Xian) and the more benevolent Tang Dynasty that followed. If great poetry flourished, such endearing whimsy of Tang terracottas like these court ladies could also mark a zenith in what is too often ephemeral art. Contemporaneous with the meteoric rise of Islam and the promise of Carolingian Renaissance with Charlemagne further West, Tang Dynasty art also represents the best of early Medieval China when Dark Ages worldwide are followed by more light.

Tang Dynasty mingqi terracotta figurine, late 8th c. (image in public domain)

Tang Dynasty mingqi terracotta figurine, late 8th c. (image in public domain)

Despite the direct gazes of these terracottas – although not as archtypes since each one appears to be mostly unique – even when the eyes are barely visible, a note of whimsy can be found where the greatest detail resides: the unusually rendered faces of these ladies which are not exactly open but mostly hinting at emotions under the surface. Changing fashion allowed for beauty to be expressed in these rather plump faces, much like plus-size models in current fashion modes, as “plumpness” seems to have been not not only acceptable but valued in this phase of Tang aesthetics, especially since visibly having enough food has often been a periodic status symbol since the Paleolithic and especially in China where food scarcity was too often a given with perennial high population. But it is also the emotive range on the faces that cannot be masked. They are sure of themselves, strong-willed, often politely smiling, full of character and even whimsy, somehow avoiding scrutiny and yet not to be crossed. It is also highly likely that many of these terracottas faces are portraits of real people rather than merely fashionable caricatures.

Tang Dynasty Terracotta mingqi tomb attendant, 8th c. (image in public domain)

Other than brighter pigmented colors – although mostly faded because they were often painted with organic material hues – the ladies’ clothing is most often subordinated to the facial verity; here the glory of Chinese aesthetics reflects how important subtlety should be perceived with intellectual reflection as expressing the high value of irony in Tang Dynasty art. Whatever might be conveyed in the whisper of emotions on these faces, what is unsaid is so often of greater significance than what is said. Due to court formalities and ubiquitous social hierarchy, these ladies may not have been allowed to fully express themselves, but they don’t actually need to be effusive. It’s rare in art of any culture where such ambiguities and subtlety are so remarkable, especially when these terracottas are not of the primary tomb residents but merely their attendants. A question worth asking is whether the terracotta artists could possibly be representing themselves and their families for posterity and eternity alongside the elite deceased?

Tang Dynasty mingqi terracotta figurines (image in public domain)

Here a snatch of poetry by the immortal Li Bai is apropos to conclude here, but rather like a conversation that really never finishes, and equally subtle and poignant:

“When first my hair began to cover my forehead,

I picked and played with flowers before the gate.

You came riding on a bamboo horse,

And circled the walkway, playing with green plums.

We lived together, here in Changgan county,

Two children, without the least suspicion.

When I was fourteen, I became your wife,

So shy that still my face remained unopened.”

(excerpted from Chang’an Memories)