By Andrea M. Gáldy –

The Hanoverians on Britain’s Throne 1714-1837. A series of exhibitions at Schloss Herrenhausen and other venues, Hanover and Lower Saxony, 17 May to 5 October 2014, www.royals-aus-hannover.de

Ralf Bormann, “The Art Collection of Count Johann Ludwig von Wallmoden-Gimborn”, in Katja Lembke (ed.), The Hanoverians on Britain’s Throne 1714–1837. Catalogue Lower Saxony State Exhibition at Landesmuseum Hannover and Schloss Herrenhausen from May 17th until October 5th, 2014, Dresden 2014, p. 238-261; Cat. No. H1-H106 ibid., p. 407-435.

Three hundred years ago the House of Hanover succeeded the Stuarts to the British throne by the Act of Settlement. Since Queen Anne had died without surviving issue her Protestant Hanoverian relatives moved to Britain. Four Georges and one William were going to rule over Britain and Hanover during a period that saw two major uprisings against Sassenach kingship in Scotland in 1715 and 1745, the loss of the American colonies in 1783. Universities were founded, for example, Goettingen, as well as the British Museum and Kew Gardens. George Frederick Handel had moved to England in 1710/11; he took British citizenship and was going to write the music for the Hanoverian court. These were the heydays of the European Grand Tour when British as well as Northern European aristocrats travelled for pleasure and education to the countries in the South, in particular to Italy. Using such journeys, which might well take several years, also as an extended shopping trip in search for paintings, antiquities and objets d’art, young, well-heeled men visited the main sights of Florence, Rome, Venice and Naples but also enrolled at Academies in Turin in the company of a tutor. Some of the main collections of antiquities still displayed at English great houses, for example at Holkham Hall (Norfolk), were amassed by grand tourists who also bought books, manuscripts, prints and drawings.

This summer the west wing of Schloss Herrenhausen, set in the midst of large and beautifully kept parks, offers the reconstruction of parts of a collection brought together by count Johann Ludwig von Wallmoden-Gimborn (1736-1811). The natural son of George II was raised at the English court. Well-educated at the University of Goettingen, he experienced the latest trends in collecting and display suitable for an aristocrat and gentleman in his position at first hand.

Funded by his royal father, young Johann Ludwig went abroad on the obligatory grand tour and bought significant numbers of antiquities and paintings. The collection was sold after his death in 1818 and while this led to the dispersal of the paintings, the antiquities were largely kept together and are currently on loan to the Archaeological Institute of the University of Goettingen, founded after all by George II. The current exhibition has brought together a number of highlights to be displayed in an attempt to reconstruct the former collection and its display pre-1818. It shows that Wallmoden’s treasures were more than a mass of valuable objects but the determined effort of the count to present himself as a worthy, if illegitimate member of the House of Hanover and thus to underpin his own dynastic ambitions.

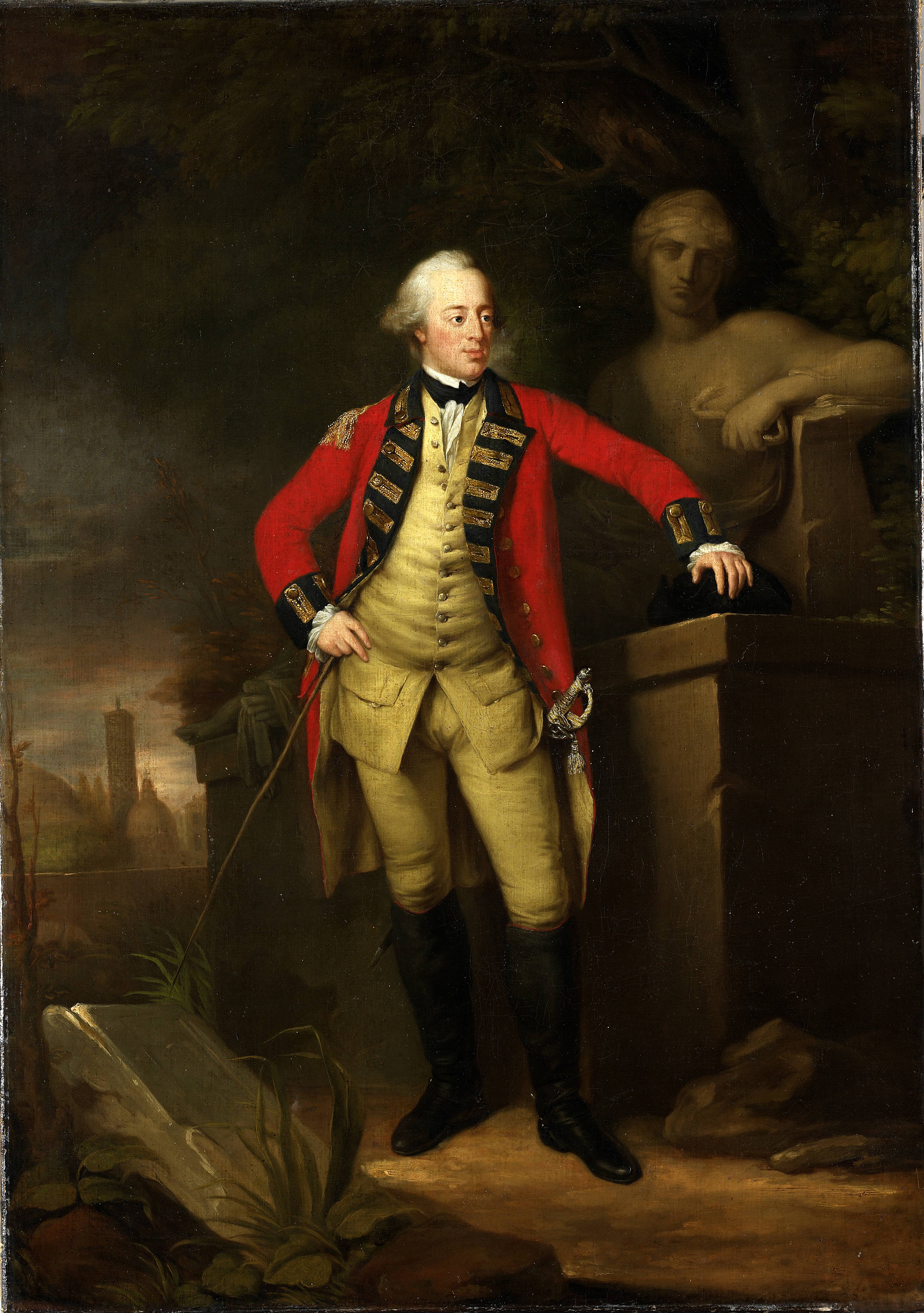

Johann Ludwig Wallmoden may have indulged in the usual pastimes of his fellow tourists, including that of having his portrait painted in front of ancient statuary. Nonetheless, he was travelling on a mission to acquire a collection: he also needed to pick up the most successful ways to present it and through it himself. Like many a collector before and after he was inspired by the Medici collections at the Uffizi and in particular by the Tribuna, an octagonal shaped room off the top-floor corridors of the gallery, flanked by further exhibition rooms. Set up by the end of the sixteenth century after the Medici had been ennobled and raised to the rank of grand dukes of Tuscany, this “temple to the arts” was sumptuously appointed by Bernardo Buontalenti and housed some of the most valuable pieces from the Medici collections. Two centuries later, between 1772 and 1778, Johan Zoffany was commissioned by Queen Charlotte to paint the Uffizi Tribuna (Royal Collections, Windsor Castle); the artist not only crowded further objects, not normally displayed in the Tribuna, into the exhibition space, he also filled it with the portraits of Florentine dignitaries and British expats and art connoisseurs.

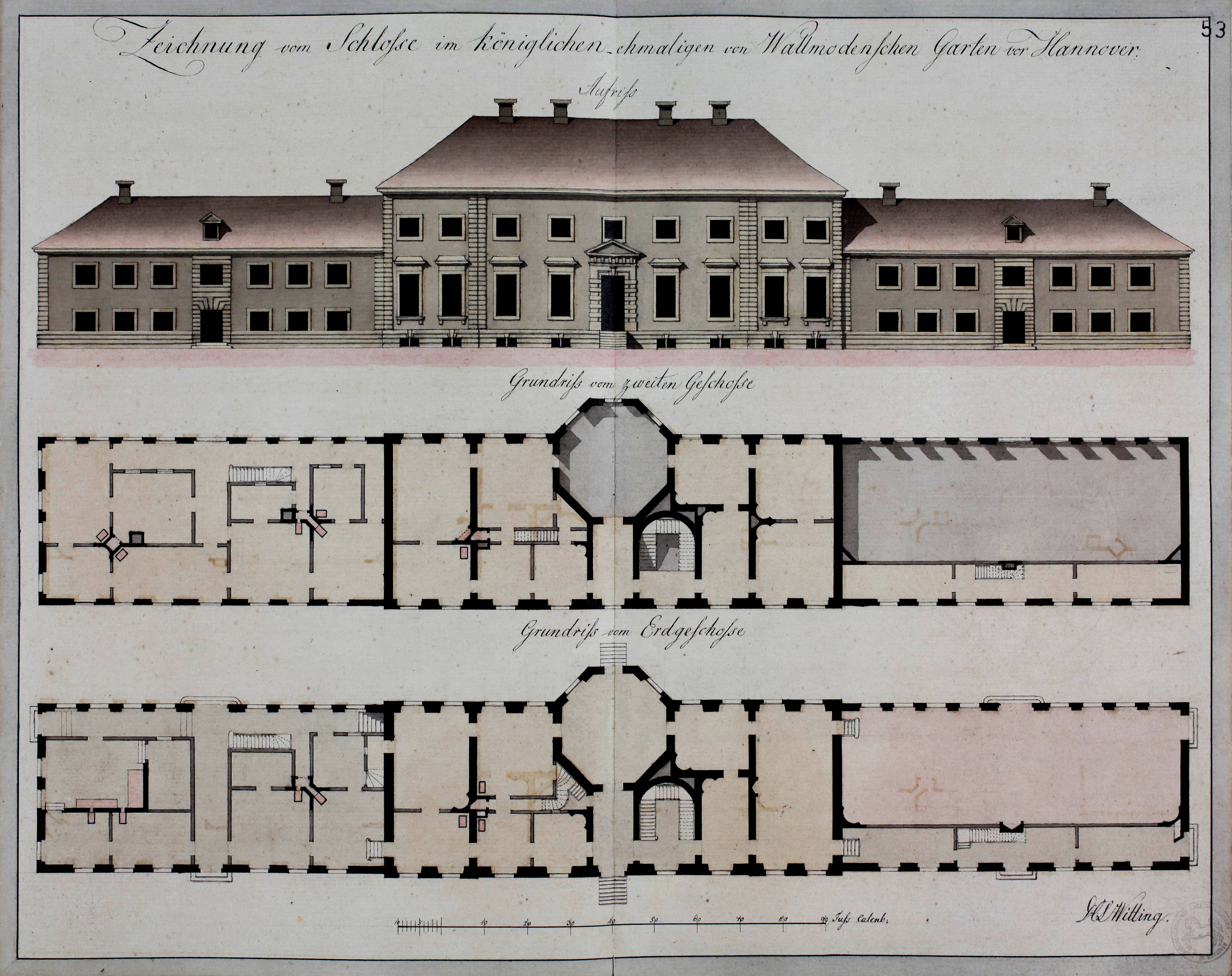

Allegedly, the royal patron was not amused when she first set eyes on Zoffany’s painting. Probably Queen Charlotte had expected an exact depiction of part of the Medici collections rather than a conversation piece featuring quite as many grand tourists of the realm engaged in sales negotiations regarding Raphael’s Niccolini-Cowper Madonna. We know that Wallmoden purchased another Raphael Madonna and we can tell that he was impressed by the Tribuna to the extent that he modelled his own collections after the Florentine display: he set up a gallery next to an octagonal display case in the Wallmoden Palais he had eventually built for himself at Hanover (today Wilhelm Busch Museum).

This may have had more than one reason: aristocratic collectors in Georgian England may have acquired their art and antiquities mostly in Rome but they found inspiration at Florence and in particular at the Uffizi which they visited in great numbers. In Florence, the British consul Horace Mann, depicted as standing between the Venus of Urbino and the right leg of the Medici Venus Pudica, ran a profitable side-line as art dealer. Perhaps more to the point to someone in Wallmoden’s position, the original Medici owners, now extinct in the male line and replaced by the House of Lorraine, had not joined the ranks of nobility until the 1530s while they had used their collections and massive support of the arts to strengthen their dynastic claims.

The display in Hanover was modelled after the Florentine exhibition in the Uffizi Gallery under the Medici. Paintings and antique statuary were shown side by side as had been the custom for centuries. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, the Real Galleria underwent a major overhaul under Giovanni Pelli Bencivenni who disposed of the Medici Armoury and reordered many of the other exhibition categories. It was his task to create space for many more paintings by streamlining the collections – a change of display which was leading in due course to the foundation of up-to-date specialised museums such as the Florentine Archaeological Museum.

Wallmoden’s collection of ca. 550 paintings and nearly 90 antiquities, the latter acquired with expert help provided by Johann Joachim Winckelmann, made quite an impact on visitors of the eighteenth century well able to appreciate the artistic refinement of the works of art as well as the princely ambition of their display. Before the count’s death an illustrated catalogue may well have been planned; as it happened this project was not executed in time but some of the highlights of the collection were copied in a series of drawings by Johann Gerhard Huck by 1798. These drawings were pasted into the Album Kielmansegg in 1814 and, together with the sales catalogue of 1818, provided the curator of the exhibition, Ralf Bormann, with crucial information for the collection’s reconstruction. Thus it has been possible to show that not only were most of the foremost pieces gathered together in the Hanoverian Tribuna – they also corresponded to works of art displayed at the Florentine Tribuna, either thematically and/or in terms of the artist as in the case of Pietro da Cortona’s Expulsion of Hagar (Hanover) and the Return of Hagar (Florence).

While it is a shame that the collection could not be reassembled at the Wallmoden Palais, the current exhibition brings at least parts of Wallmoden’s possessions back to life. It is the merit of painstaking detective work by its curator as well as of the generosity of many a private collector as well as of the archaeological institute of the University of Goettingen. Sadly, by 5 October the collection will be dispersed a second time and one can only hope that at least a virtual/digitised Wallmoden collection will be created in due course.

Image credits:

Figs. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6: © Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover.

Fig. 2 public domain, courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig. 7: © Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv, Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover.

Fig. 8: © HRH Ernst August, Hereditary Prince of Hanover, Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg, Schloss Marienburg / Archäologisches Institut Göttingen / Photography: Stephan Eckardt.