By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

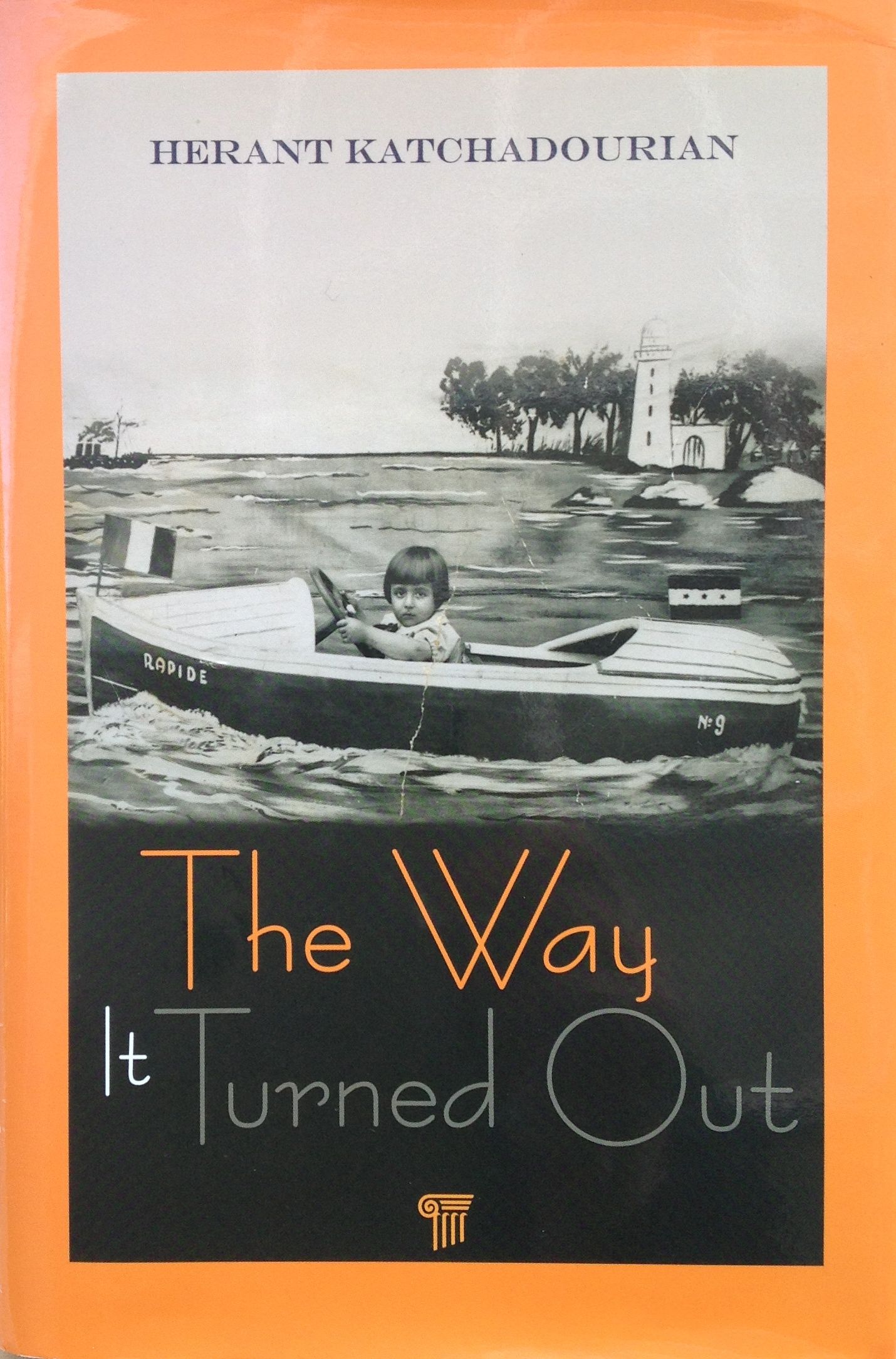

Memoirs are by nature usually suspect; this one truly raises the bar. Here honesty is cherished and myopic self references are at a minimum. Especially when they are filled with rationalizations of bad behavior, railing curses against foes or aimed at generating sympathy for a gargantuan mea culpa, memoirs can make a reader bilious, wondering what has been omitted or embellished and how much to believe. Celebrity tell-alls are also often kangaroo courts against critics. There are mesmerizing exceptions, however, like Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, where the literary merit and brilliant observations outweigh nearly any deficiencies or idiosyncratic selective memory. Herant Katchadourian’s The Way it Turned Out (Pan Stanford. 2012) is in the delightful latter category, much like Proust replete with an amazing facility of sensory detail and customs, some exotic, others amusing but always compelling. This is a literary odyssey from Iskenderun to Beirut to America as the saga of an Armenian savant who provides a tremendous legacy and remembers so much of an age rapidly passing from the fading Ottoman and post-colonial Near East. Personal stories and anecdotes intermingle with family and village history, wars, displacements, migrations and the changing faces of Anatolia and the Levant as countries have struggled with national and ethnic identity and religious conflicts as well as jealousies against the industriousness of people who have worked hard to preserve a legacy for culture and family. Sadly, history is too often written in such a revisionist plan that denial is the only way to describe it. This memoir addresses underlying elements in the complicated nature of culturicide.

Although not a book about any kind of monoculture, one of the most interesting questions in the book is about what it has meant to be Armenian in the diaspora across many landscapes in Turkey, Lebanon and the rest of the world. Armenians are depicted as proudly self-reliant and hardworking in many crafts and profession, but mostly known for their grit and perseverance. Armenia is acknowledged as being one of the very first Christian countries in the world since Late Antiquity and maintaining Armenian religious identity in recent centuries has sometimes resulted in persecution that may be tied to religious intolerance in the Middle East. Two brief warm anecdotes about Armenian identity are worthy of repeating. In the family kitchen at Stanford, California, where Herant Katchadourian spent an academic career at Stanford University (medical school professor, psychiatrist, dean and vice provost), Herant’s aged mother brought from Beirut in her last years ruled the kitchen. “Cut that garden parsley back to the nub when you harvest it. Like Armenians, it flourishes the more you cut it down.” Or another moment was when Kai told his mother that in America her prayers should be in English, not in Armenian. She wryly assented in recalling the suffering of her people across history, saying, “Yes, I’ve wondered if God hears prayers in Armenian.” Armenians are not always given their historic due and few know that the third red phase of the beautiful Iznik tiles – one of the Ottoman splendors of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul – in the 16th century were inspired and pioneered by Armenians from the red clay of their homeland, like the lead article image at top (serendipitous that it is in a world-class collection in Lisbon bequeathed by Gulbenkian, another visionary Armenian who made his sizeable fortune in the fuel industry). Likewise, the peerless Ottoman 16th c. architect Mimar Sinan who built Istanbul’s great Süleymaniye Mosque and the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne was actually Armenian. That Armenian connection notwithstanding, the author appears in the memoir in a modest account believing that citizenship in the world is a grander scheme and a deeper responsibility.

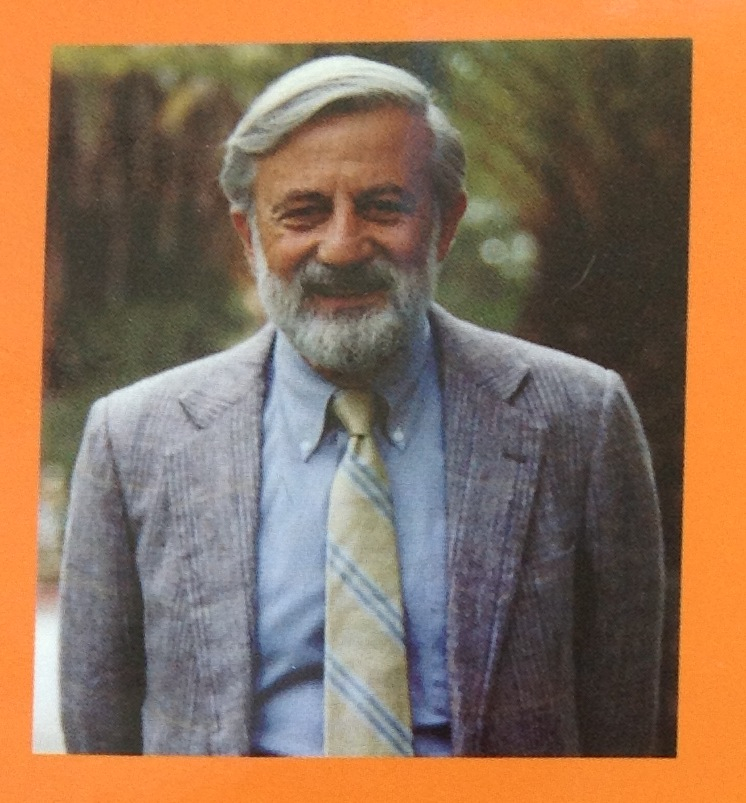

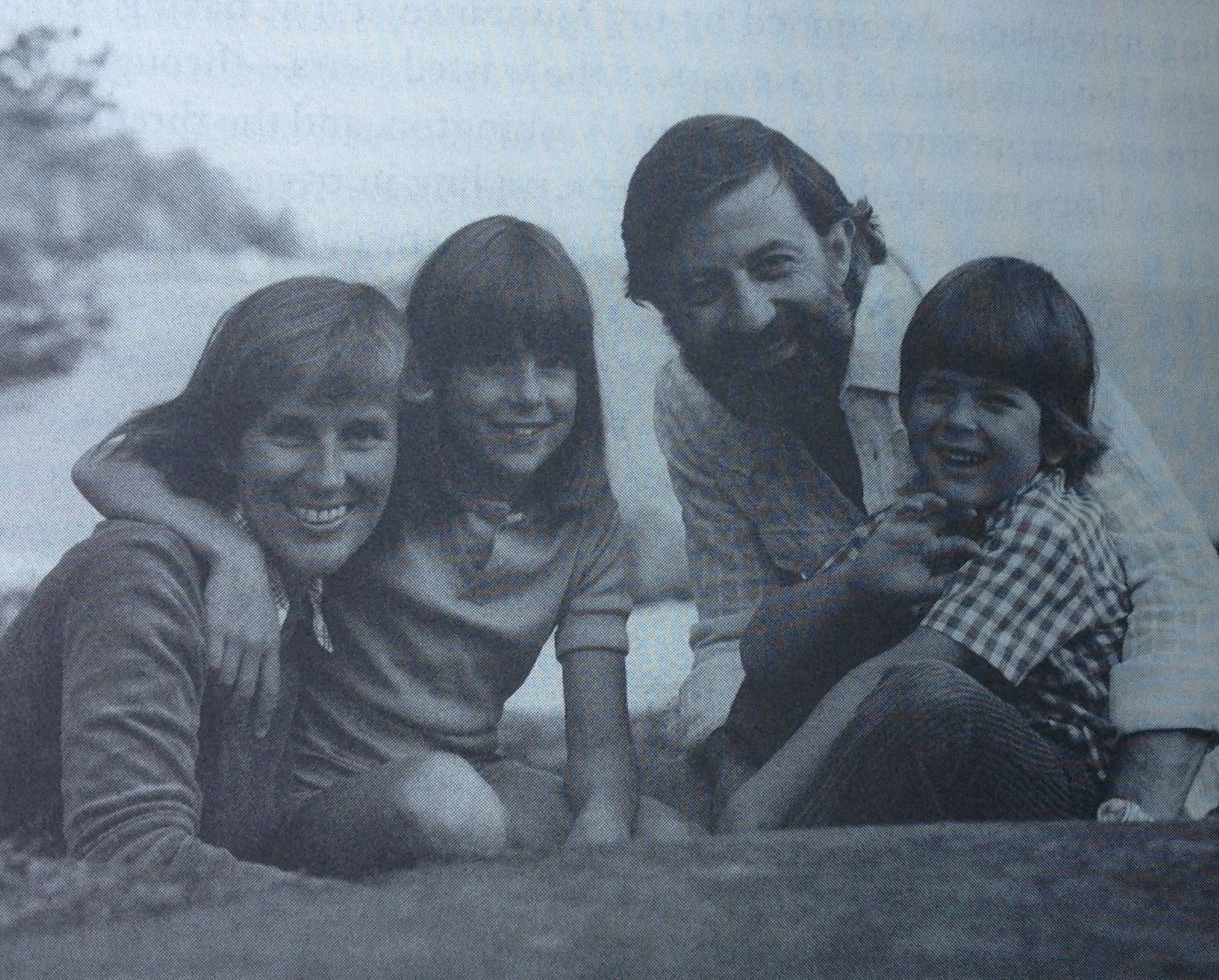

Herant Katchadourian is not only a citizen of the world and fluent in five languages – words in many languages appear in the text with perfectly apropos explanations – but also a man of faith who manages to be intellectually astute and professionally deep with no trace of self-congratulation as his remarkable career unfolds in the memoir. One of the best reflective chapters in the book is near the end (chapter 12) “A Healing Place” where as a scholar and deep thinker Herant muses about solitude and theology on the family island retreat in Finland. In contrast, also one of my favorite passages in the book and full of latent sensuality, was when as an adolescent on the bus in Beirut, he and a budding girlfriend relish their backsides touching in the lurching urban bus, sending tantalizing shivers of delight and fantasy in a world where chaperones kept tight guard over wayward youthful hormones. Later, Katchadourian’s medical training and career, first in Lebanon and Bethlehem, was followed by medical residence in the United States and, after a return to Beirut including teaching at the American University Beirut, he met his wife Stina and had a prestigious tenure at Stanford University where they raised their daughter Nina (now an award-winning artist) and son Kai) until retirement. Herant’s wife Stina is a noted poet, translator and Esperanto expert. At least one of the textbooks Herant wrote became a perennial bestseller across the Anglophone world and his insights into human behavior have gifted several generations through his teaching and writing. His emeritus years have been notably reflective, and his leadership in philanthropy is treated surprisingly humble despite how influential it has been across many arenas and even countries.

Most of us would be satisfied with even a modest sampling of one of Katchadourian’s accomplishments, and while he is aware of his impact in several countries, his modesty and honesty are endearing. This memoir is so worth the read, a page turner, and will reward any reader with its vast personal knowledge about the Middle East, full of intelligence, wit and wryness. Would that every memoir was so thoughtful and believable.