By Patrick Hunt –

One of the features found across Maya sculpture in different media and materials – stone relief, plaster relief, wood and ceramic figures – appears to be a certain amount of heightened caricature and lack of proportionality, in the opinion of this researcher possibly to accentuate imagery seen from a relative distance from the perspective of the viewer, in this case the Maya themselves in their hierarchical courts. It is also likely in this researcher’s opinion that the most important feature in Maya human sculpture is often the actual head and face, which in a majority of reliefs and paintings is in profile. Full three-dimensionality is therefore not as common, which can also be somewhat derivative of the medium used. Some Maya sculptural canons were conservative, as noted at Tikal and the surrounding Central Petén in stela monumental imagery established since the Early Classic (ca. 400 CE) but stylistic innovations were introduced at sites like Palenque and Yaxchilan by the Late Classic (ca. 700 CE). [1]

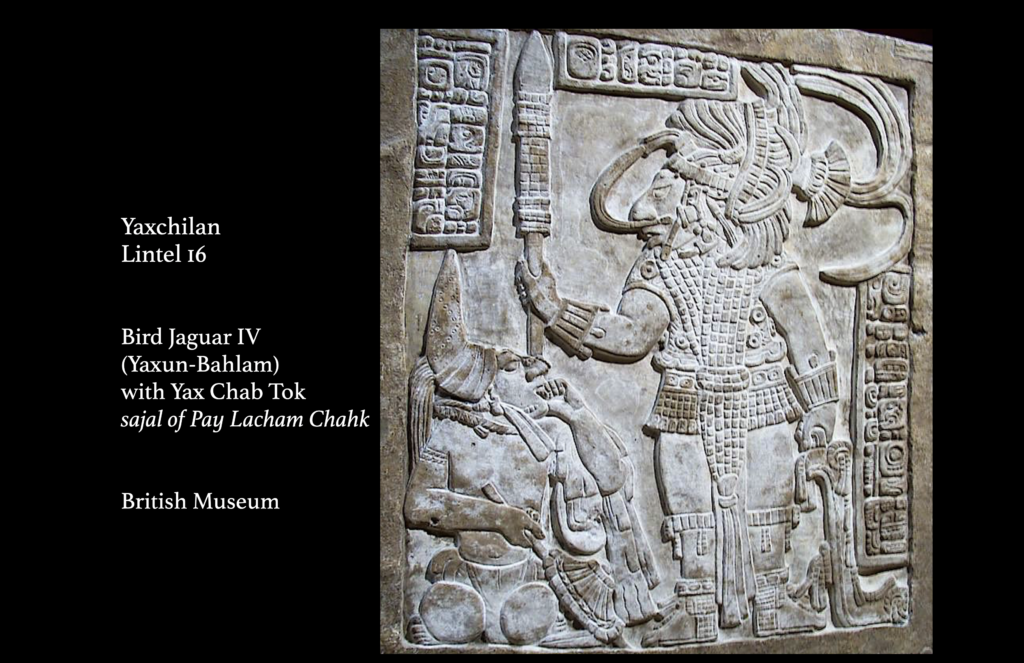

As this researcher has published elsewhere on selection criteria of materials such as stone,[2] the materials also lend themselves to a particular amount of detail or lack thereof, in which latter case, larger than life Maya caricature (depicting oversize heads and disproportional shortened bodies) may not be so much intended as portraiture but rather displaying some idealizing of features and instead manifesting the portrayal of power, for example in the humiliation of captives, and in the dynastic succession of generations of royalty or other rituals. At times, great status and prestige are deliberately highlighted in costume details of royal or elite jade pectorals, necklaces and bracelets as well as quetzal feather headdresses, as seen for example in Yaxchilan lintels, [3] many of which details Ian Graham carefully replicated in his coverage of over 200 sites and 2,000 monuments. [4] The careful and at times over-the-top rendering of Maya status elements in jade jewelry and other costume details may have been an important aesthetic consideration of the elites, as is often typical across hierarchical cultures.

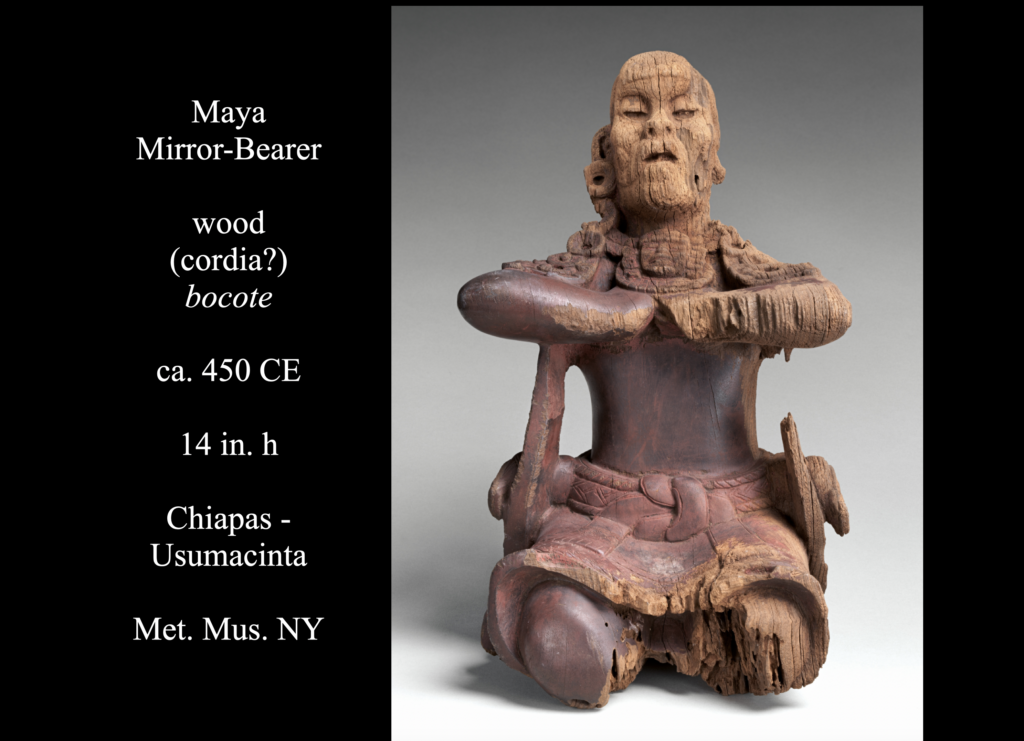

While jade as a stone material was highly valued, its hardness – aiding its durability – did not lend well to sculptural detail, as one of the better examples, the Palenque Royal Jade Plaque (14 cm h) in the British Museum may show. Unfortunately, while some materials like limestone are both highly available in the Maya region and easily workable, limestone is not ideally very durable in the tropical environment and expected deterioration may have even been factored in longterm thinking, so that explicit detail may not have always been as important as the overall dynamic expressed. In fact, as this author has published in prior studies, workability and durability are often in inverse proportion to each other: the more workable, the less durable and vice versa in that the less workable, the more durable. The same durability limitation can be said of wood as even more susceptible to deterioration as organic material, which unlike limestone had to be kept inside or away from the elements where hydrolysis (dissolution by water), thermolysis (dissolution by heat) and photolysis (dissolution by light) destroy the integrity of the sculpture and especially detail, Very few Maya wood sculptures have survived except when found stored longterm in dry caves or similar contexts.

One such very rare wood Maya sculpture example is the Early Classic mirror-bearer of probable cordia (bocote) hardwood seen at the Met Museum NY, and while not especially well-preserved around the head, is nonetheless useful and representative.[5] This heightened organic deterioration is because tropical climates usually have high indices of all three agents of destruction.

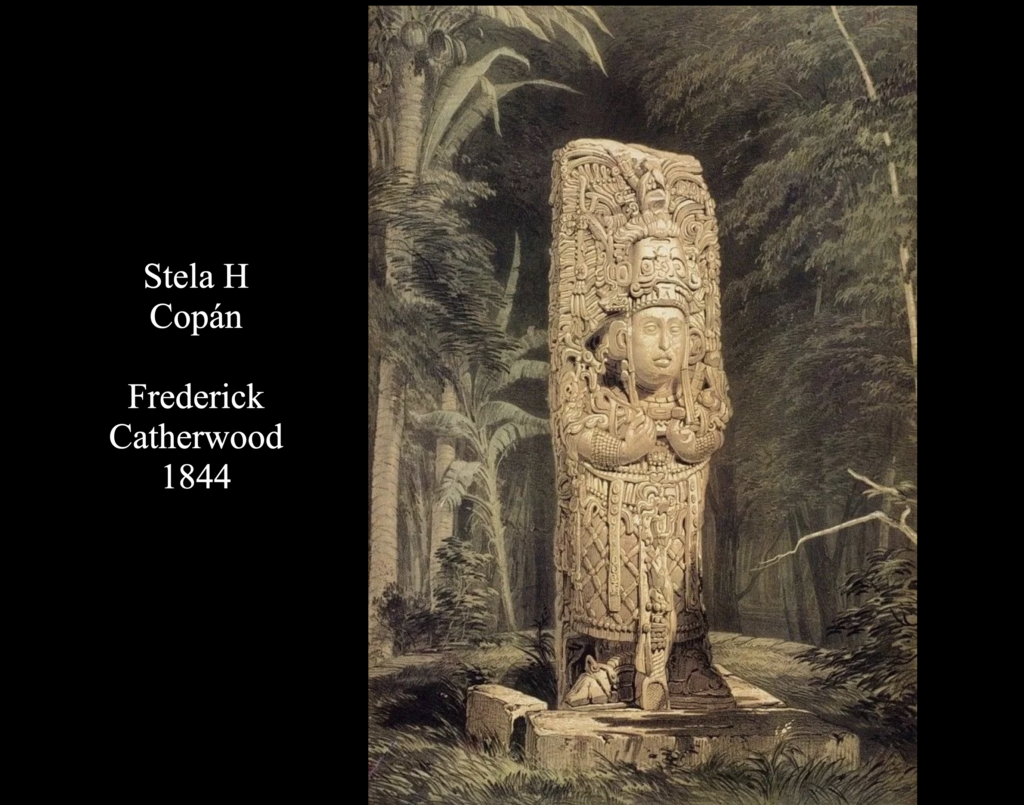

Some examples of Maya sculpture express a few Maya aesthetic ideas as well as environmental constraints better than others. The Quiriguá and Copán often three-dimensional monumental stone figures are deeply carved in high relief, and also very likely to dramatically accentuate light and shadow but also possibly to offset expected deterioration over time. The extant reliefs at Copán like Stela H also show discernible surface loss (e.g., note heavily-eroded skirt and loss of sharp edges)) relative to their state in exceptionally-detailed watercolors Frederick Catherwood made in situ ca. 1844.

Many Maya sculptures are formal and static as state monuments as canons required, others far more expressive. Palenque sculptors chose a fine-grained limestone for much of the relief subjects of the interior wall panels,[6] some of which have survived better than others, especially if outside. Some plaster reliefs at Palenque seem to have been mostly moulded rather than carved and were kept out of external tropical climate elements and thus are better preserved, along with the carved limestone Palace Tablet as seen inside Lord Pacal’s tomb complex inside the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque.

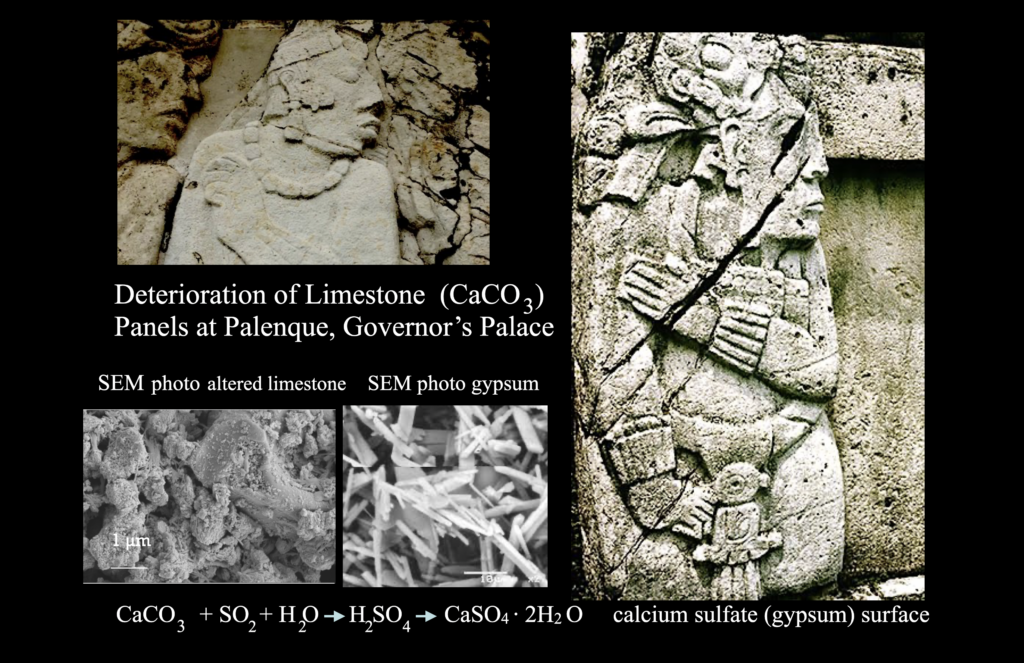

But external limestone reliefs at Palenque – for example, especially the Governors Palace Courtyard – show intense deterioration in the 20th-21st century where exposed to the elements, in some cases losing more than 50% of the surface relief. Yaxchilan limestone relief lintels have survived better than at Palenque while carved to almost the same original depth. One modern culprit in addition to the overall climate at Palenque may be the effects of airborne burning of petroleum by-products like gas venting from the Coatzalcoacos and Villahermosa PEMEX complexes – in the latter case only about a hundred miles away – such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), which converts to sulfuric acid (H2SO4) in combination with airborne or aeolian water vapor and then also converts the surface limestone (calcium carbonate CaCO3) to very soft highly-soluble calcium sulfate (CaSO4-2H2O) in its dihydrate form – essentially gypsum – or similar soluble compounds that may not dry out for months especially during rainy seasons. In the dry season I collected with permission from Merle Greene Robertson and others at Palenque in 1989 some of this recrystallized “gypsum” in the form of byproduct polyps, subsequently analyzed by SEM + EDS at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL, London. and subsequently published in the Proceedings of the Septima Mesa Redonda Palenque 1994 after my paper at that conference in 1989 [7] Thus, being out in the natural but increasingly polluted elements at Palenque exacerbates limestone solubility. No doubt the Maya sculptors had no expectation of such heightened and accelerated deterioration for some of their materials like limestone, especially modern anthropogenic pollution, but they must have been aware of normal tropical deterioration of surface limestone over time and wood in the short term.

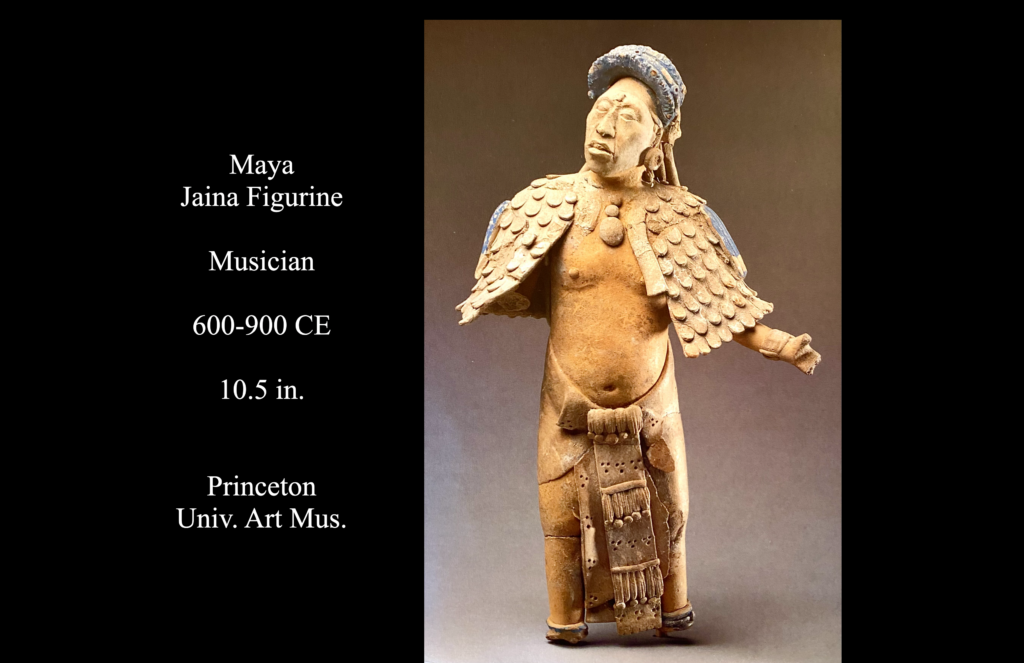

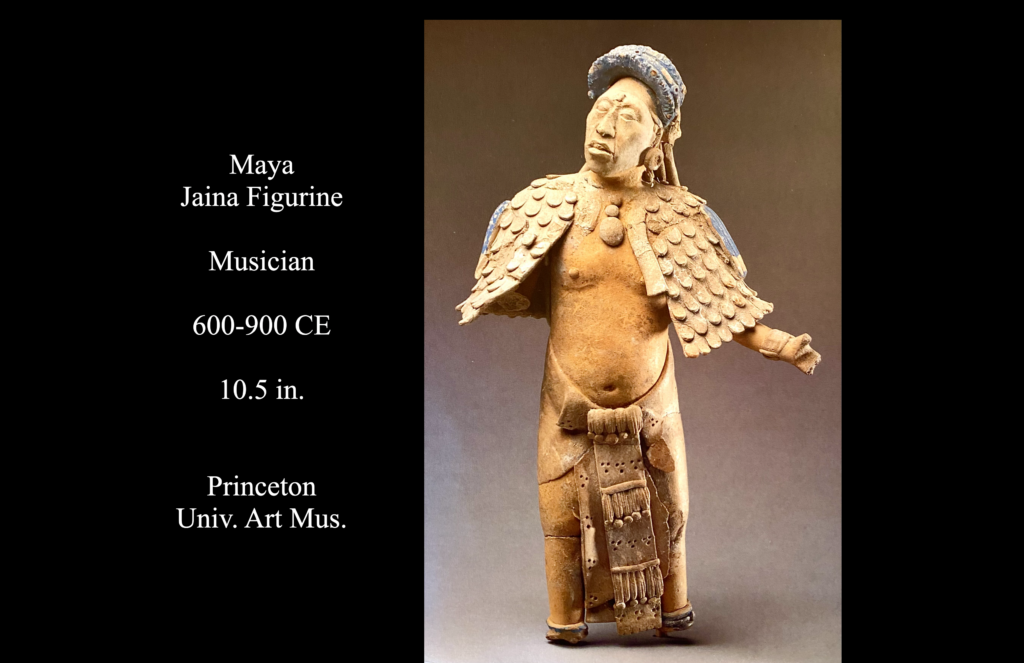

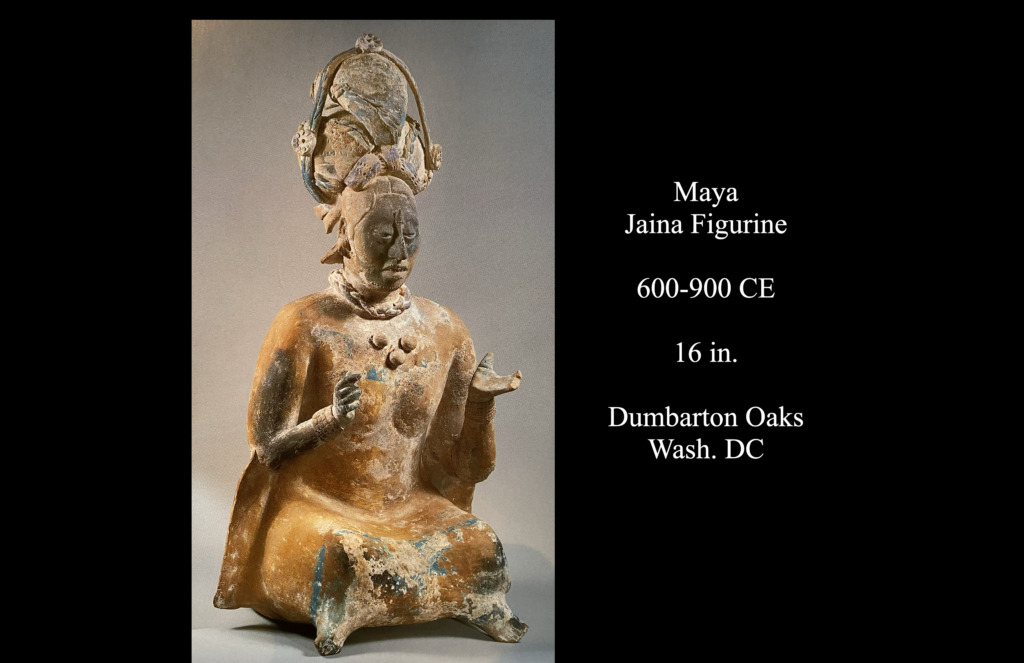

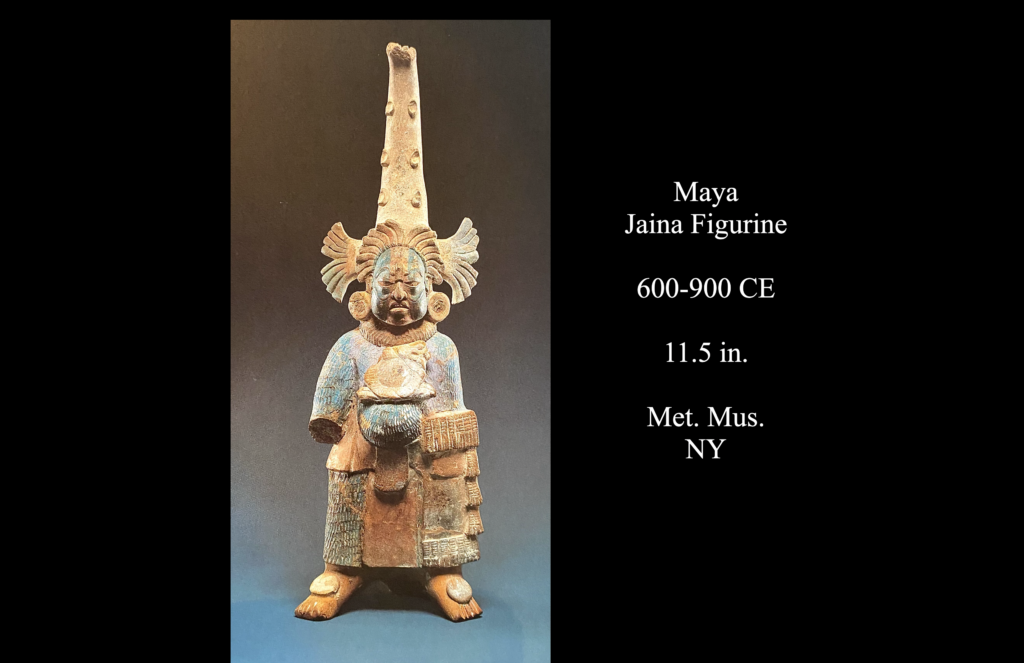

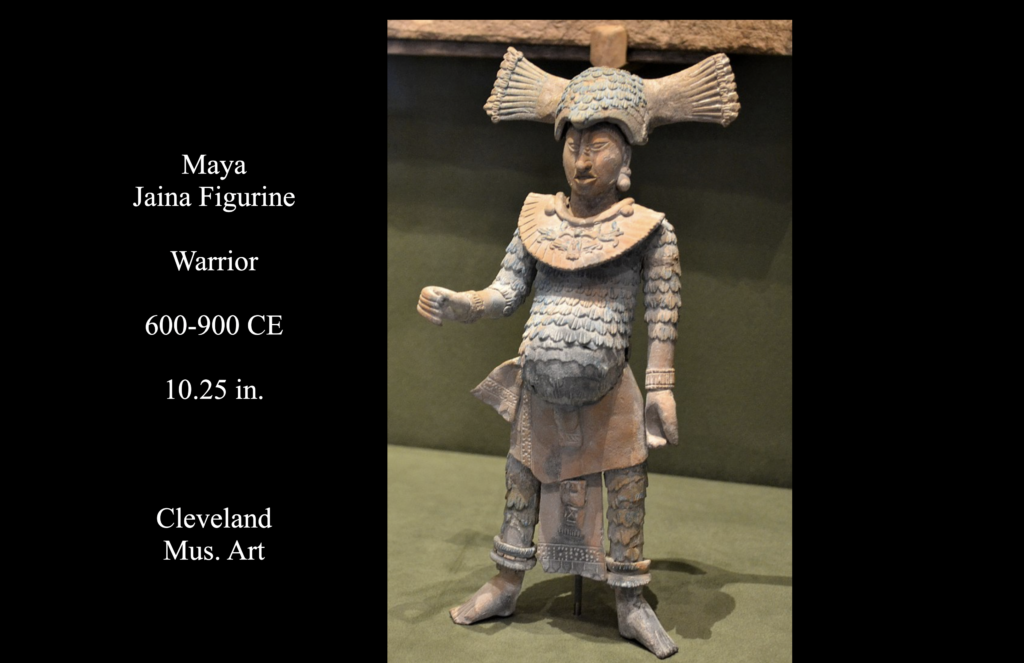

This solubility factor leading to deterioration may make the medium even more important. That is likely why the most resilient of Maya media over time in tropical contexts is fired ceramic highly resistant to deterioration, and a medium which is also important for rendering three dimensionality. A plastic, moldable material like clay may offer the best potential for three dimensionality because it is not the same as a reductive material like stone or even wood, both of which must be carved away as opposed to worked when soft as unfired fine clay, which can include additive surface details. Perhaps the best expressions of Maya sculpture, then, can be seen in the Jaina Island (just off Campeche mainland in the Yucatan) ceramic figurines (ca. 600-900 CE) from mostly Late Classic necropoli there, and although small and generally under 20 inches high, these may have the optimum possibilities for realism, especially facial expressions and possibly intended portraiture. It is also not uncommon for these ceramic Jaina figurines to be enhanced by the “Maya Blue” pigment possibly from attapulgite (polygorskite) including mines and sources near the Rio Azul. [8] These small Jaina ceramic figurines are remarkable for expressing individual personalized details rather than static monumental manifests of power.

Jaina Figurines in all their exquisite detail can be seen in collections at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C., LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), the Metropolitan Museum of New York, Princeton University Art Museum, among other venues. Many of these Jaina ceramic figurines can be viewed or easily photographed, as in the case of the Villa del Balbianello FAI (Fondo Ambiente Italiano foundation) collection in the Lake Como, Italy, where I have visited many times for National Geographic Expeditions and was asked by FAI to study and publish their collection where possible.

The Jaina figures from the necropoli number in the hundreds, show great individuality or originality, and are extremely high quality in representation, with the finest examples moulded by hand, [9] some of which are seen below.

One Jaina ceramic figure (three-dimensional) from the Princeton Collection (10.5 in h) is identified as a musician, with unique headdress and back decorated in Maya Blue. Even while incomplete due to breakage, both the facial expression and physiognomical details as well as costume and posture are highly realistic. Another Jaina ceramic figure (three-dimensional) from Dumbarton Oaks, a seated female on knees tucked under her (16 in h) has an elaborate unique headdress. She is also decorated with Maya Blue and while her facial expression may or may not necessarily be negative about sadness or loss but is somber, her hand gestures communicate either something held which is missing or relate some paralanguage cultural detail. Apropos sophisticated discussions about Maya gestures and paralanguage (e.g., incorporating Piercean semiotic theory and Laban movement analysis) have elsewhere discussed the likely possibilities of reading gestures and postures in dance, a kinetic art form not unique to the Maya but perhaps with valuable cultural Maya hallmarks, and while some seminal studies focus on painted polychrome vessels, these hypotheses are nonetheless applicable here. [10]

Yet another Jaina ceramic figure (three-dimensional) from the Met. Mus. NY collection, again decorated in Maya Blue (11.5 in h) also has a unique costume and headdress with quetzal feathers, large rounded ear flares along with other elements and facial features that are highly individual, including heavy jowls. Finally, the Jaina ceramic figure (three-dimensional) from the Cleveland Museum of Art (10.25 in h), said to be a warrior, slightly potbellied, and greatly decorated in Maya Blue again has a unique individualistic costume, perhaps of rows of quetzal feathers, and individual facial rendering.

He has a uniquely wide open stance and different arm gestures – possibly having held missing weapons – and his helmet even detaches from his head. These remarkable, richly-decorated Jaina ceramic figures likely represent the best Maya examples of sculpture partly because of their private individuality rather than their public monumentality, even if not meant to be seen by many.

These are just a few examples of iconic Maya sculptures – especially the well-preserved Jaina ceramic figures – that demonstrate cultural benchmarks for aesthetics, status, costumery, possible emotive portraiture and at times strong individualism. Maya sculpture is well-represented especially in ceramic rather than soluble stone or other organic material like wood, both of which a tropical climate can too often destroy.

Notes:

[1] Mary Ellen Miller. The Art of Mesoamerica from Olmec to Aztec. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991 repr., 145.

[2] Note the author’s extensive discussions of sculptural stone criteria for other materials including earlier Olmec sculpture “Olmec Stone Sculpture: Selection Criteria for Basalt”, W. J. McGuire et al. eds. The Archaeology of Geological Catastrophes. London: Geological Society of London Special Publication 171 (2000) 345-54, partly excerpted and expanded from the author’s Ph.D. Dissertation, Provenance, Weathering and Technology of Selected Archaeological Basalts and Andesites. Institute of Archaeology UCL (University of London) 1991, esp. ch. 6, 192-98. For other stone selection arguments and associations thereof, also see Christopher Pool, Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, esp. 65, 109-10, 140-1.

[3] Carolyn Tate. Yaxchilan: The Design of a Maya Ceremonial City. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992, esp. chs. 3-4, (…Regalia, Imagery…Scenes of Royal Ritual), 50-84 and 85-110.

[4] Ian Graham. Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard-Peabody Museum, 1975.

[5] James Doyle. “Ancient Maya Sculpture” Essays from Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, 2016

(https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/313256).

[6] Miller, 145-46

[7] Patrick Hunt. “Maya and Olmec Stone Contexts: Limestone and Basalt Weathering Contrasts.” Septima Mesa Redonda de Palenque Proceedings 1989. Merle Greene Robertson and Virginia Fields, eds. Precolombian Art Research Institute. San Francisco: PARI, 1994, 261-67.

[8] Dean Arnold. Maya Blue: Unlocking the Mysteries of an Ancient Pigment. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2024.

[9] Miller, 156-7

[10] Mark Wright and Justine Lemos. “Embodied Signs: Reading Gesture and Posture in Classics Maya Dance.” Latin American Antiquity 29.2 (2018) 368-85.

Note all images are either in public domain our are the author’s photos.