By Jess Taylor –

The physical layout of the Athenian defensive Long Walls always seemed to me historically unique, being long and narrow, and aligned so closely together, raising my curiosity.

In short, the civic center of Athens developed around its famous acropolis located away from the sea. Then, in the 5th Century BCE, Athens adopted a strategy of maintaining a strong navy for primary defensive and economic well-being. The strategy was successful and naturally increased Athen’s reliance on her navy and her principal port at Piraeus, located 7km distant. This spatial separation between the city and her port created the need to insure they were never disconnected. The Long Walls are the result of Athens addressing this military vulnerability over the course of the century.

Thucydides is the earliest source to use the term τὰ μακρὰ τεὶχη or, “the long walls”[2], writing:

ἢρξαντο δὲ κατά τοὺς χρόνους τούτους καὶ τὰ μακρὰ τείχη Ἀθηναῖοι ὲς θάλασσαν οἰκοδομεῖν, τὸ τε Φαληρόνδε καὶ τὸ ἐς Πειραιᾶ.

“About this time the Athenians began to build the long walls to the sea, that toward Phalerum and that toward the Piraeus” [10].

This article has two parts. The first reviews the course of construction of the walls and provides an overview of the historical factors that motivated the construction phases. The second provides an overview of the archeological remains. Maps and photographs are used throughout to provide visual context.

Rebuilding After Salamis

In 480 BCE the Athenians and Greece faced a true existential threat. Following his victory to the north at Thermopylae, the Persian King Xerxes and his superior military forces were advancing toward Athens. The perceived peril was such that the legendary Athenian general Themistocles convinced his fellow Athenians to abandon their homes and sanctuaries and evacuate to the nearby island of Salamis, where he laid his famous trap that resulted in the unlikely yet decisive naval victory over Xerxes at Salamis.

When the Athenians returned home shortly thereafter, they found the Persians had destroyed much of Athens and totally destroyed the Acropolis – thoroughly “razing and burning it” (Herodotus, History 8.53). Themistocles set about to quickly rebuild Athenian defenses against future threats. Beginning in 479 BCE, the Athenians resumed and completed work on the defensive wall surrounding their main port at Piraeus (first initiated by Themistocles in 493 BCE). Around the same time, the city walls of Athens were reconstructed with remarkable haste, a process evident in the current archaeological record.

Long a proponent of naval superiority being key to Athenian protection and prosperity, Themistocles’ military leadership and naval policies laid the groundwork for other Athenians to take a leading role in the formation of the Delian League in 478 BCE. The league united most Aegean poleis to fund, build and maintain a powerful naval fleet for defense and trade – organized and led by Athens.

Thus, within just a few years, these events set the stage for Athenian naval dominance in the Aegean, provided security against a quick Persian return and marked a pivotal moment when Athens began to rely increasingly on naval strategy to secure its future.

Figure 1 shows the Themistocles defensive circuit walls as of 476 BCE for Athens and Piraeus along with the location of the city of Phaleron, the traditional port of Athens prior to Piraeus, and the Strait of Salamis. Xerxes paused at Phaleron while plundering the Athenian countryside before allowing his fleet to be lured into the Strait of Salamis.

The modern routes of the Kephissos and Ilisos rivers are shown crossing the plain between Athens and Piraeus, emptying into the Bay of Phaleron. In ancient times the Ilisos river maintained a westerly path and was a tributary to the Kephissos river [7].

Zooming in, Figure 2 adds the principal roads and city gates connecting the circuit walls. The northern road, named the Hamaxitos, meaning cart-road, is the principal road connecting Athens and Piraeus [8]. Travelers would leave Athens either by the Diplyon gate complex or by the Peiraic gate and arrive to the Asty gate of Piraeus. The southern Phaleron road exited Athens at the Phalirou gate and made its way directly to Phaleron. City walls for Phaleron are not depicted as no traces have yet been found and it’s considered likely they never existed [2].

In the 5th century BCE, the alluvial lands between Athens, Piraeus and Phaleron were occupied by the demes of Xypete and Echelidai and were used for agriculture and pasturage. Additionally, the area was used for horse racing and religious activities, containing many sanctuaries. Many smaller roads and paths must have crisscrossed the land.

Water was available via the rivers and from wells, augmented by cisterns. The area was flat except for the Sikelia Hill. It was marshy and unusable along the Bay of Phaleron and the river delta [1,2]. The clear break in the modern building pattern along the Kephissos river delineates the historical extent of its flood plain.

Prior to the development of the port of Piraeus, Phaleron Bay was the traditional port and naval station of Athens. Evidence from gravesites indicates Phaleron was in use for centuries prior, while Piraeus has little archeologically until approximately the 5th century BCE [5]. Phaleron was a weak port, lacking permanent port facilities and being vulnerable to piratical raids; the development of Piraeus solved this problem.

The Legs

By the 460’s BCE, concern grew regarding vulnerability to a superior army occupying the land between Athens and Piraeus, thereby cutting Athens off from its navy and the sea.

Increasingly Athens had relied on its navy for trade and protection. Emerging hostilities with Sparta heightened Athens’ need for enhanced security measures, and a larger military strategy was forming that emphasized naval resources over army resources.

In response, Athens embarked on an unusual and ambitious project to build defensive walls linking the city to the sea. In the event of a land attack, the new walls would allow Athens to shelter rural populations behind the walls, while maintaining essential connections for communication, troop movements, and supply lines through its ports, which were protected by its powerful navy.

Construction of the Long Walls (τὰ μακρὰ τεὶχη), or the “legs” (τὰ σκὲλη), as they were sometimes referred to, began near 461 BCE under the leadership of Kimon and were likely completed under Pericles by 458/7 BCE (Figure 3). The new Northern or Peiraic Wall, connected Athens to Piraeus. The new Phaleron or Phalera wall linked Athens with Phaleron. Despite the decline of Phaleron as a port, compared to Piraeus, its inclusion in the defensive strategy highlights its ongoing significance.

The coastal gap between Phaleron and Piraeus, remained unprotected, presumably because there was no perceived vulnerability given the difficult terrain provided by the marshy coastline and confidence in the Athenian navy.

Each wall was roughly 6 km long. They were robust and imposing having widths and heights on the order of 5 and 10 meters, respectively, and designed to be resistant to 5th Century siege tactics. They featured stone foundations and socles topped with mudbrick structures, gates, towers, and stair-accessible wall-walks shielded by parapets. Over time, roofs were added to these wall-walks.

The Middle Wall

Dramatic events during 446 BCE resulted in Athens losing control of its land empire in central Greece. Allies Euboea and Megara revolted, Megara successfully. They lost Boeotia in the Battle of Coronea and repelled a Spartan invasion of Attica, all of which led to the negotiation of the Thirty Years’ Peace with Sparta in 445 BCE. The treaty kept Athens in control of the seas, but she gave up her land buffer beyond Attica.

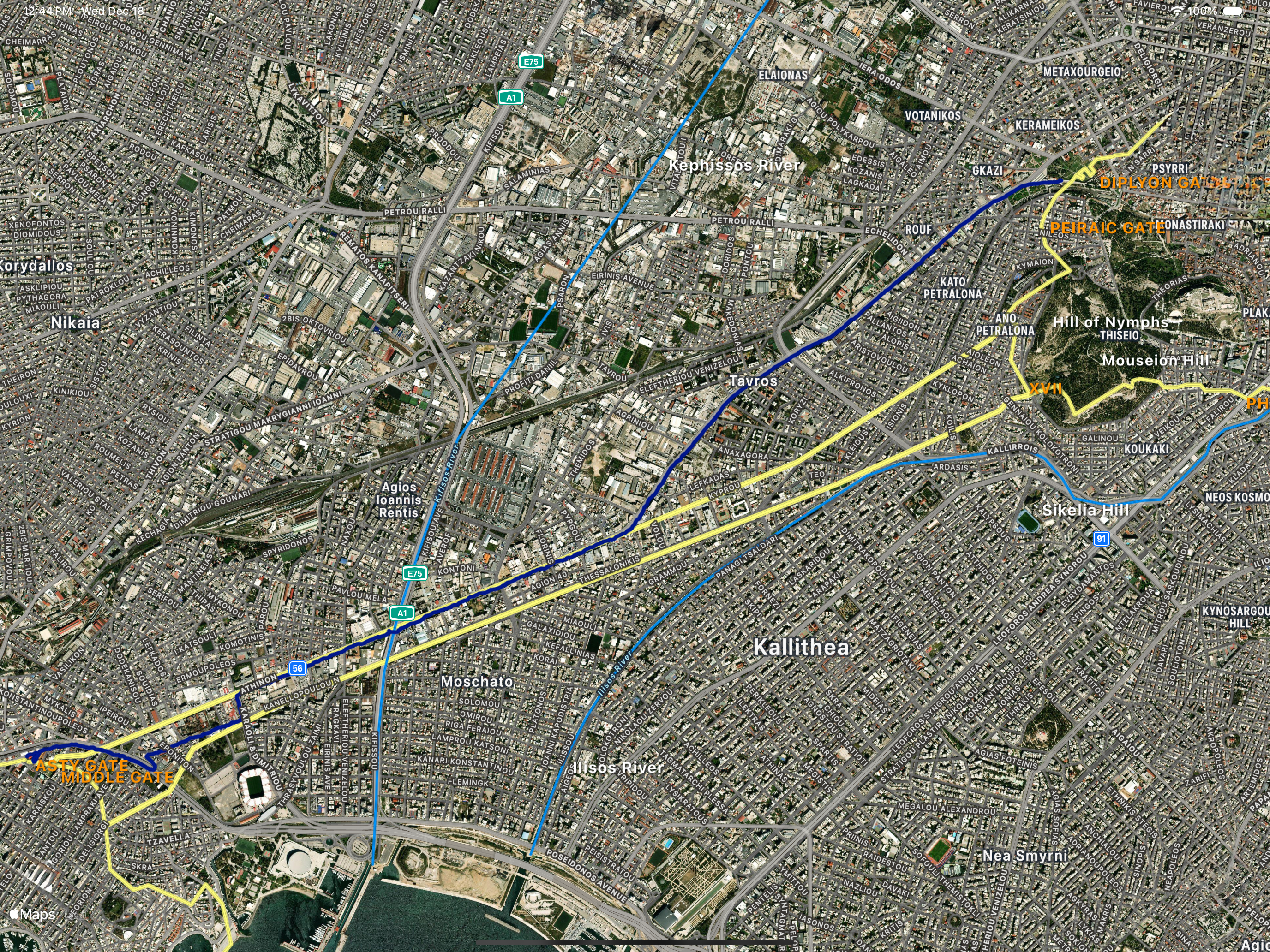

In response, Pericles proposed the construction of a new “Middle” wall. Begun near 443/2 BCE, this wall ran parallel to the Northern wall keeping a consistent separation of 183 meters to the south, except at its endpoints (Figure 4).

With the Phaleron wall already connecting Athens with its harbor at Phaleron, the new Middle wall was initially seen as a backup fortification. It could serve as a fallback if the Phaleron wall was breached or if invaders landed successfully between Phaleron and Piraeus. Due to the narrow separation of the Northern / Middle walls, it required fewer resources and manpower to defend than the Northern / Phaleron wall configuration.

The Koile road, connecting the Koile deme via Gate XVII in Athens to the new Middle gate in Piraeus, ran between the Northern and Middle walls, making it completely protected and therefore the newly critical route between the Athens and Piraeus. As the importance of the port of Phaleron waned in favor of Piraeus, both economically and strategically, this new configuration ensured the necessary link between Athens and its maritime gateway remained intact.

By 430 BCE, or perhaps a few years earlier, the three Athenian Long Walls were in place.

Put To the Test

The Peloponnesian War began in 431 BCE, marking the beginning of a prolonged conflict between Athens and Sparta. Pericles, the famous Athenian leader of the “Golden Age”, formulated the following defensive strategy that capitalized on Athens’ Long Walls:

- Defense:

- Avoid direct land battles with the superior Spartan army, instead rely on the fortified walls to maintain a secure connection between Athens and Piraeus.

- Encourage Athenians to abandon their rural properties and withdraw behind the city’s walls during Spartan invasions, safeguarding maritime trade and alliances.

- Offense:

- Use naval power to conduct operations abroad, sustain the empire, and secure provisions via sea routes.

The walls, first begun in 461 BCE, remained untested from invasion until 431 BCE. Beginning in 431, however, and continuing until 425 BCE the Spartans conducted annual summertime raids (excepting 429 and 426 BCE), each lasting about 40 days, causing a periodic retreat of the rural Athenians behind the walls.

Facing real danger, the walls protected the withdrawn Athenian citizens and proved to be successful deterrents from direct attack. In fact, while certainly closely inspected by the Spartans, there is no evidence any serious attempt was made to breach them [2].

Catastrophically, the plague struck Athens in 430-427 BCE, significantly reducing its population by as much as 25% and claiming the life of Pericles. It was a generational setback. As famously described by Thucydides, many of the sick and dying sequestered within the narrow confines of the Northern and Middle walls.

In 425 BCE, after the Battle of Sphacteria near Pylos, direct Spartan invasions into Attica paused, reducing the walls’ immediate strategic importance. But in 413 BCE, the Spartans returned, establishing a permanent garrison at Deceleia, north of Athens, and prompting the Athenians to consolidate fully behind their walls year-round, relying completely on access to Piraeus for supplies. As before the walls provided protection for the rural population and deterred attack. Not without hardship, the Periclean strategy seemed to work.

Somewhere between 431 and 404 BCE the Phaleron wall was abandoned in favor of the Middle wall. Why or when is not clear, but Thucydides notes the Phaleron wall was still being manned in 431 BCE.

Shifting Military Dynamics

The disastrous Sicilian Expedition in 415-413 BCE severely weakened Athens’ naval capabilities. Although initially afterwards Athens maintained its naval power in the Aegean, the financial backing by Persia allowed Sparta to challenge and eventually dominate the Aegean by 405 BCE.

The decisive Spartan sea victory in 405 BCE at the Battle of Aegospotamoi in the Dardanelles finally crippled the Athenian navy, leading to the successful naval blockade of Piraeus and a subsequent siege of Athens. Ironically, with the Piraeus blockaded, the Long Walls became militarily irrelevant due to Athen’s loss of her supply chain.

By April 404 BCE, Athens, starved and exhausted, capitulated. Sparta’s demands for surrender included the partial dismantling by the Spartans of portions of the Northern and Middle walls near Piraeus, and the entire fortifications around Piraeus. The Athenian circuit wall was left intact.

The Phaleron wall was not discussed in the surrender proceedings, reinforcing the theory of prior abandonment. Hence forward the term “Long Walls” referred only to the Northern and Middle walls, with the Middle wall taking on the name of “Southern” wall.

Epilogue: The 4th Century BCE

Following their surrender to the Spartans, the Athenians gradually repaired their Long Walls and rebuilt their navy during the Corinthian War (395-386 BCE). For a time, the walls were considered crucial once again for the defense of the Athens-Piraeus connection.

Subsequent enhancements in the 330s BCE adapted the walls to counter new and improved siege technologies from Macedonia, shifting from mud brick to more durable stone constructions and perhaps higher heights. Repairs occurred again at the end of the 4th Century, but after 404 BCE the walls were never called upon for defense. Entering the 3rd Century BCE the walls lost their strategic value for good and fell into disrepair.

The Archeological Record – What’s Left?

Comparatively little remains of the Long Walls, but their existence has left a permanent imprint on the landscape that is easily appreciated today. The Long Walls themselves were part of a larger system of gates and roads, as we have seen, so we will review the primary archeological remains from the perspective of the principal roads connecting Athens and Piraeus. Afterall, these were the conduits of daily life that the walls were meant to protect.

Note, after the Phaleron wall was abandoned, the Middle wall became known as the Southern wall. For continuity, however, we’ll continue to use the term Middle wall for the remainder of the article.

The Koile Road (Ὁδὸς διὰ Κοὶης)

Departing Athens

The view provided by the photograph in Figure 5 looks southwest towards Piraeus from Mouseion Hill [4], the high point in Philopappos Park (now commonly known as Philopappos Hill due to the later 2nd Century BCE Philopappos Monument situated upon it). It provides an overview of the plain lying between Athens and Piraeus and where the Northern and Middle walls were laid.

Directly ahead in the distance is the port of Piraeus. The Phaleron Bay is to its left. The Strait of Salamis is to its right. Separating Mouseion Hill from Piraeus is ~7 km of flatland, the corridor the walls were meant to protect, now densely populated by modern Athens.

Note the long, rectangular “greenbelt” in the center right of the photograph, seemingly connecting the hill and the port. Using the greenbelt and this vantage point, we can readily gain a sense of the position of the Northern and Middle long walls. The greenbelt demarks the modern metro line that directly follows the trace of the Middle wall. The Northern wall was positioned ~ 200 meters to its north, running parallel to it before splaying off to the right, towards the Hill of the Nymphs.

Returning to Mouseion Hill, the deme of Koile, the departure point of the Koile road, is situated just to the right and down in the valley below. The Koile road began here and followed a nearly direct path down into the plain to Piraeus, fully protected between the Northern and Middle wall.

You can walk down the hill and visit the remains of the deme of Koile and a 600-meter stretch of the heavily trafficked Koile road, including clearly visible cartwheel tracks cut deeply into the local stone. Figure 6 shows a portion of the road leading downhill through Koile. Piraeus is seen in the background. You’ll note the steep ascent or long decent across rocky terrain, a drawback to this route.

Figure 7 provides an aerial view of Philopappos Park and the Acropolis. The Koile Road began at the Philopappos Hill and traversed the Koile deme located in the valley between the Hill of Nymphs and Mouseion Hill, all of which resided within the Athenian defensive walls as shown.

The traces of the Northern and Middle walls and their connections with the Athenian circuit wall are also shown in Figure 7. There are no remains to directly support this commonly depicted wall configuration, but it’s generally accepted the Northern wall terminated near the Hill of the Nymphs, in the modern Ano Petralona neighborhood, while the Middle wall terminated near and south of the Mouseion Hill [1].

Continuing southwest, the Koile road exited the circuit wall at Gate XVII [2] and continued towards Piraeus nearly directly, hugging the interior of the northern wall, as depicted in Figure 4, and terminating at the Middle gate in Piraeus.

Connecting City to Port

Visually prominent well into the 19th century, almost nothing of the Northern and Middle walls remains above ground today.

Being nearly perfectly straight and possessing gravel embankments and stone foundations the walls were natural building targets, first for Roman aqueducts, and much later, for modern means of transportation (especially considering the marshier areas near Piraeus).

Thus, in 1835 the first motorways linking Athens to Piraeus followed much of the course of the Northern wall along what is now known as Kyprou, Peiraios and Athinon Streets. Later in the 19th century, the railway connecting Athens and Piraeus was established on top of a long section of the Middle wall. By the beginning of the 20th century, little of the walls remained above ground.

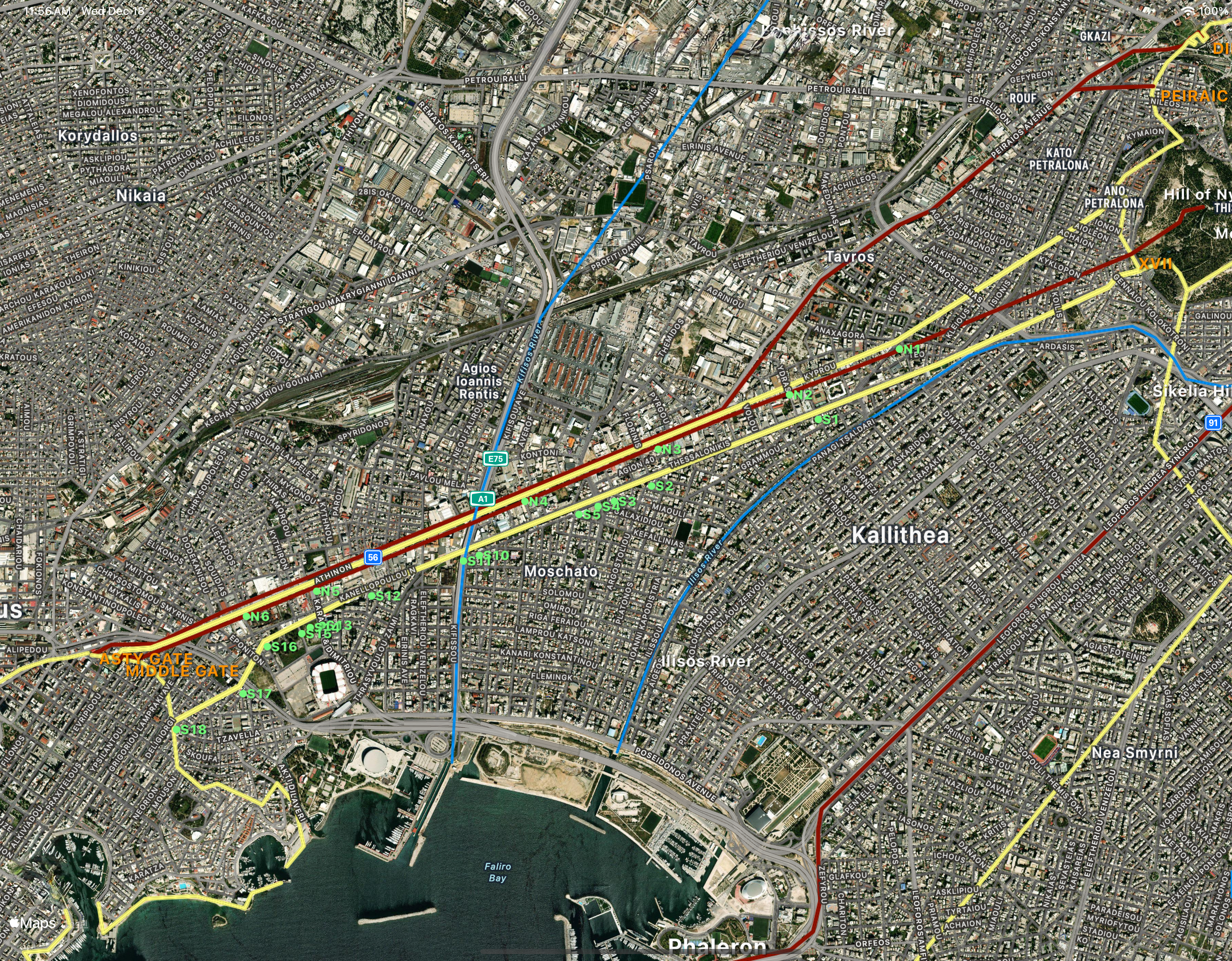

Conwell [1] presents a catalog of known wall remnants along their respective courses. Consisting of mostly foundational stone, Figure 8 locates sites N1 – N7 corresponding to the Northern wall and sites S1 – S18 corresponding to the Middle wall superimposed with the traces of the Northern and Middle walls that follow the modern roads and railways. Their alignment provides a strong correlation between the ruins and the roads.

Arrival to Piraeus

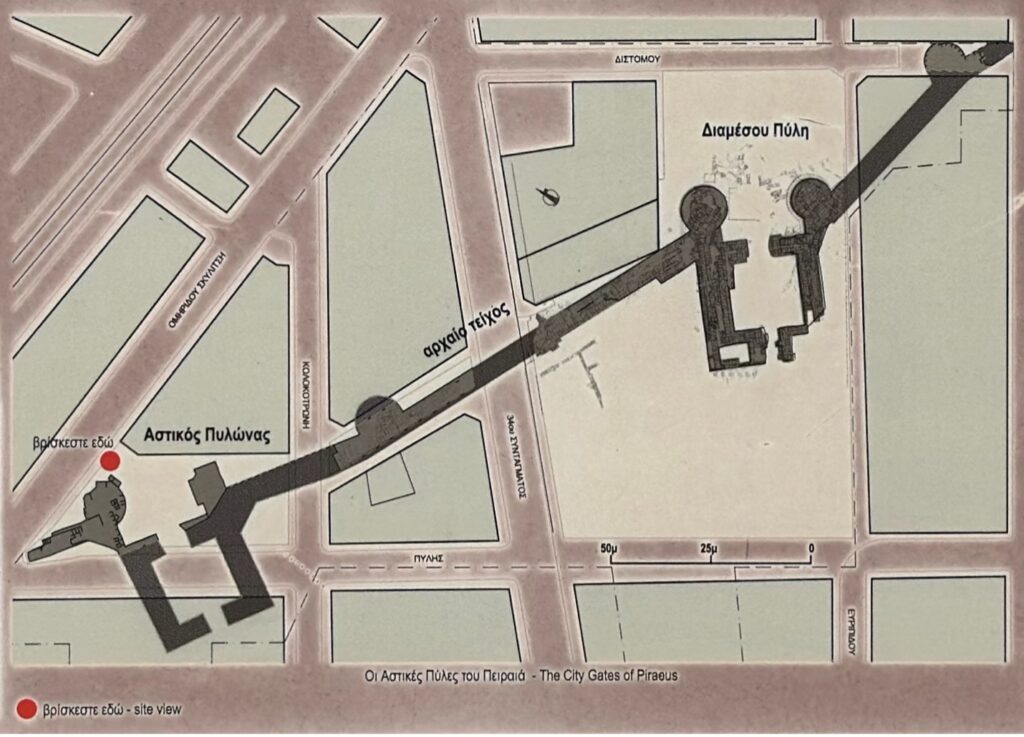

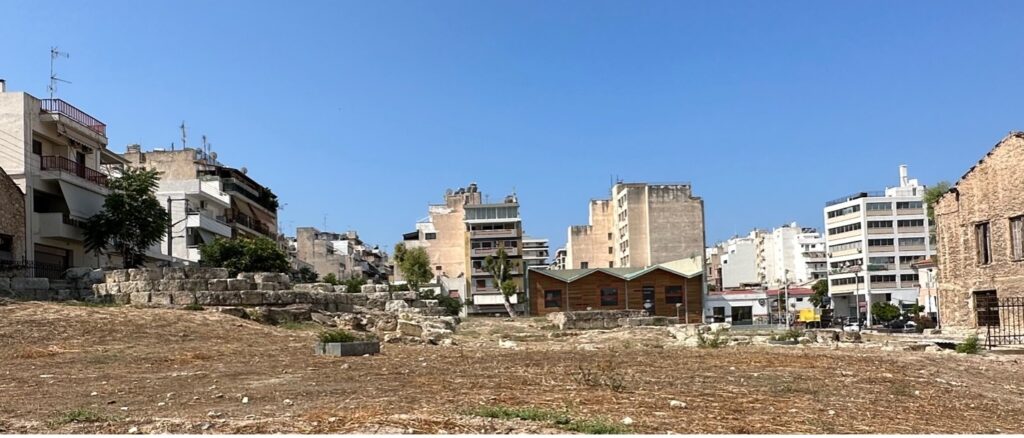

An interesting and compact set of ruins can be found in modern Piraeus. Within two city blocks, one can view remains of the Asty gate, Middle gate, the junction of the Northern wall with the Piraeus circuit wall, and a section of the Piraeus circuit wall running between the gates. This intersection must have been quite the hub!

Figure 9 presents an aerial view of the archeological site which resides about 20 minutes by foot from the Piraeus train station. The Asty gate (left) is located at the corner of Pylis and Omiridou Skilitsi Streets and the Middle gate (right) is located near the corner of Evripidou and Distomou Streets. An exposed section of circuit wall lies between the two gates on Kodrou Street. The Northern wall attached just to the left of the Middle gate [5]. Also depicted is the protected Koile road entering the Middle gate on the inside of the Northern wall and the unprotected Hamaxitos road entering the Asty gate from the outside of the Northern wall

Figure 10 presents a diagram of the Asty and Middle gates taken from the archeological site plaque. Both gates are formed in the shape of a Diplyon, which is comprised of a rectangular courtyard with two opposing entrances. Most of the Asty gate lies beneath the street while the Middle gate is completely exposed. The Northern wall is not depicted in Figure 10 but intersected near to the left of the Middle gate, separating the two gates.

Focusing on the Middle gate and the terminus of the Koile road, Figure 11 looks south into the Middle gate as if you were approaching it on the Koile road from between Middle and Northern walls. The foundations of one of the round towers can be seen of the left. The Northern wall would have entered the picture on the right.

Figure 12, looking east, shows a portion of the Piraeus circuit wall connecting the Asty gate (behind the photo) and the Middle gate. The Middle gate complex can be seen in the background across the street.

The terminus of the Middle wall with the Piraeus circuit wall is located farther east on Pylis Street as shown in Figure 13. No longer visible, it is known from a topographic survey conducted in 1870s. Located on the south side of Dheliyiorghi Street, midway between Pylis and Evangelistrias Streets, the location corresponds to Conwell’s site S18.

The Phaleron Road

As there are no convincing traces left of the Phaleron wall or road [1,2], this review will be brief. Conwell [1] presents a review of the literature that shows different proposed paths for the wall, including differing terminuses with the Athenian circuit wall and the sea near Phaleron. This article presents the configuration adopted by Conwell [1,2].

The Phalirou gate at Athens is known to exist under the intersection of the Phalirou and Donta Streets [6], near to the Acropolis Museum, but remains unexcavated (Figure 14).

Archaeological finds along this route, particularly near the ancient city walls of Athens, include tombs and remains of funeral pyres. These discoveries support the idea that the ancient and modern routes are aligned and that Phaleron was an essential port area.

According to Conwell, the port and walls of Phaleron have seen various stages of recognition and archaeological interest. Historically, the road connecting Athens to Phaleron was a significant artery, likely heavily trafficked due to its connection to the port. Given the lack of remains, the exact nature and status of fortifications directly at Phaleron remain unclear.

The Hamaxitos Road (Ὁδὸς ἁμξιτὸς)

We conclude with the Hamaxitos road, first introduced in Figure 3. It is considered to have been the “central artery” linking Athens and Piraeus.

Plato’s Republic begins with Socrates saying, “I went down to Piraeus yesterday with Glaukon …”. Bakewell [8] makes the strong case the road Socrates and Glaukon took was the Hamaxitos.

Departing from Athens most significant intersection, the Diplyon / Sacred Gate complex, located in the Kerameikos, the Hamaxitos circled the outside of the city walls towards Piraeus roughly paralleling modern Peiraios Street (Figure 15).

Alternatively, it could be joined by a short stretch of road emanating from the nearby Peiraic gate, located at 50 Irakleidon Street (Figure 15). According to [6], if the bar is open on the ground floor of the apartment block, you can ask to visit a portion of the gate ruins.

Figure 16 north looks across the Kerameikos. In the back, running perpendicular to the view is the Diplyon road which led to Plato’s academy and beyond. Forward towards the camera, also running perpendicular is the Sacred Way, that led to ancient Eleusis. Their respective gates are located off to the right (Figure 15). Directly in front is a well-known portion of the Themistocles circuit wall. The Hamaxitos began roughly here running parallel outside of the circuit wall.

Continuing, the Hamaxitos converged with the outside of the Northern wall near the modern intersection of Kyprou and Peiraios. From there it closely paralleled the outside of the Northern wall, following the modern Peiraios and Athinon Streets, until entering Piraeus at the Asty gate (Figure 3).

Although unprotected from land invasion, the Hamaxitos was the more approachable route to Piraeus, being flatter than the Koile road, which ascended or descended sharply while traversing the Koile deme. It was also perhaps the more scenic, not being hemmed in between two tall walls situated <200 meters apart and more importantly offered morning summer shade along the length that hugged the Northern wall [8].

Walking to Piraeus

Inspired by Bakewell [8], and Socrates, we decided to walk a modern version of the Hamaxitos road in the summer of 2024. The trace of our walk is shown in Figure 17. The journey was just under 8 km long and took 2 hours.

Leaving the Kerameikos and joining the very busy Peiraios Street, we arrived at the Northern wall at the intersection of Kyrou Street. We then followed the Northern wall trace directly along Peiraios Street, which, after crossing the modern course of the Kephissos river, changes to Athinon Street.

In the gallery of photos above we have, (left) walking south along the trace of the Northern wall on busy Peiraios Street. Who is to say the ancient cart-road was any less busy than its modern equivalent? (center) the Kephissos river at Peiraios Street, now confined within modern concrete banks and (right) the corner of Karaoli & Dimitrou Street and Andrea Mourati Street, turning in between the walls and traversing the virtual Koile road (Photos by Rachel Dinno).

Our reconnaissance told us we could no longer walk a direct line to the Asty gate due to non-pedestrian highways and railways, so we cut into the now residential region between the Northern and Middle walls at Karaoli & Dimitrou Street, crossing the virtual Koile road, and then followed Andrea Mourati Street, which led to a convenient steel pedestrian crossing of the railway tracks (Figure 18). This was much more pleasant walking than the heavily trafficked Peiraios / Athinon Streets.

Once across the tracks, we followed Omiridou Skilitsi Avenue around the hill along its very narrow sidewalk.

Along the way we passed the Middle gate, crossing the virtual Koile road again, then across the Northern wall trace, returning to its outside, and arrived directly to our destination at the Asty gate (Figure 19)!

Figure 20 shows the Asty gate approached southward from the outside of the Northern wall and the Piraeus circuit wall. The tower walls to the right and left (by the trees) demark the ancient entrance with its Diplyon courtyard covered by the building behind (refer to Figure 10).

After visiting the Asty and Middle gates, we hailed a cab and traversed the Piraeus boulevards designed in ~470 BCE by the ancient urban planner Hippodamus and enjoyed a delicious fish meal in the heart of Piraeus, inspiring us to walk the full Koile Road next year!

References

- David H. Conwell, The Athenian Long Walls: Chronology, Topology and Remains, University of Pennsylvania, Ph.D. Dissertation, 1992

- ___________________, Connecting a City to the Sea: The History of the Athenian Long Walls, Brill Academic Pub, 2008 (ISBN-13 9789004162327)

- Anna Maria Theocharaki, The Ancient Circuit Wall of Athens: Its Changing Course and Phases of Construction, Hesperia, The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume 80, Number 1, January-March 2011, pp. 71-156

- John Travlos, Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens, Thames and Hudson, London, 1971

- Robert Garland, The Piraeus: From the Fifth to the First Century B.C., Cornell University Press, 1987

- Walk the Wall of Athens, Dipylon Society for the Study of Ancient Topography, 2023

- Richard Talbert, Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, Princeton University Press, 2000

- Geoffrey Bakewell, “I Went Down to Piraeus Yesterday”: Routes, Roads, and Plato’s Republic, Hesperia, The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume 89, Number 4, October-December 2020

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Translated by Rex Warner, Penguin Books, 1972

- Original Greek: Thucydides: The Peloponnesian War, 1.107, Translation: Thucydides. The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War (p. 144). Free Press. Kindle Edition.

The article’s feature image, the three dimensional (3D) depiction of the long walls of Athens, is provided with permission by © Dimitris Tsalkanis of Ancient Athens 3D for the use of this publication only.

All maps were produced by J. Taylor using his proprietary Odyssey Map software developed on Apple’s iOS SDK (Software Development Kit) and includes satellite base map images from © Apple Maps. All additional, historical mapped data was derived from the references and incorporated into the mapping software.

For further details on the Athenian circuit wall refer to [3 and 6] and for the Piraeus circuit wall refer to [5].