Salvator Rosa, Philosophy, ca. 1645, image courtesy National Gallery London

By Natalie Vander Pol –

One of the most moving pieces to me personally in the National Gallery is undoubtedly Philosophy by Salvator Rosa (ca. 1645), which symbolizes both a love story and a bond between human thought and art.

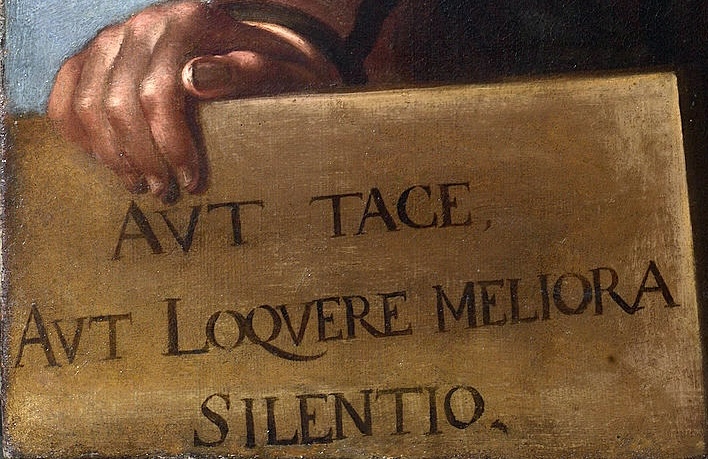

At first glance, Philosophy (45.8 x 37 in.) is a relatively straightforward painting. Rosa, perhaps to his own chagrin, was best known in his time for his landscaping paintings. He was among the first to pioneer the Baroque style, forming sublime or unsettling landscapes in his work and known for a life which was at times flamboyant in contrast to this painting. Complex mythological and allegorical subjects were also frequently his focus and pride. However, Philosophy is a direct display. In the self-portrait, Rosa depicts himself with a tilted head, a scholar’s cap, and a stern face with a downturned mouth while holding a sign or inscription. The inscription reads, “Keep silent, unless your speech is better than silence” in Latin (Aut tace, aut loquere meliora silentio). Note tace in Latin is the source of our word “tacit” as something more subtly implied than stated, as well as the word “taciturn.” Rosa’s tight-lipped mouth looks rather taciturn. The background also looks partly cloudy or stormy, especially near the top of the painting, perhaps suggesting psychological turbulence of some kind.

Latin Inscription in Philosophy

The personal intrigue over Philosophy is that it was not a lone work. Philosophy has a partner painting, Poetry. This painting shows a woman turning her head towards the viewer, with a quill in one hand and a book in the other. She wears a blue headpiece adorned with a laurel wreath with gold-lined leaves. She bears a similar serious expression to Rosa in Philosophy. The woman appears to be a portrait of Lucrezia Paolini, Salvator Rosa’s longtime partner and eventual wife.

The two paintings are made almost as perfect reflections of one another. The woman of Poetry tilts her head towards the left, while the man of Philosophy tilts his head to the right. The man’s right hand is the most forward as it moves to hold the Latin inscription. Meanwhile, the woman’s left hand is most prominent as she uses it to grasp the book. Though the paintings complement each other, there is also a noticeable contrast between the two. Lucrezia’s face appears almost entirely in light, while a shadow engulfs one side of Salvator’s face. Lucrezia is portrayed in blue, yellow, gold, white, and orange-brown apparel, making her arguably the more colorful of the two paintings. In opposition, Salvator is wearing almost only brown and black, with the exception of a thin white collar.

One perhaps endearing aspect of these paintings comes from understanding the character of Salvator and his and Lucrezia’s love story. Salvator lived a strenuous and slightly unusual life. Though he was undoubtedly recognized for his talent during his prime, his fame does not explain his circumstances. Salvator’s father died when he was merely seventeen, leaving him to become the head of the family. He began to rapidly create and sell his work in order to provide for his family, which was then in a difficult financial situation. Despite his hardships, he remained incredibly dedicated to his work. He was, by all means, quite a bit rebellious for the time. He often refused commissions and rejected patrons while pursuing his own subjects and ideas. His work was rather bizarre for his lifetime; it wholly strayed from the standard depictions of religious symbolism or scenes that were central at the time. Instead, he favored allegorical work, which very often featured scenes of witches or other noir subjects. Helen Langdon, noted Renaissance art historian and Salvator Rosa scholar, states, “The originality of his art was complemented by his creation of a bizarre and often outrageous persona, one that was provocative and arrogant, a dark outsider…” (Langdon, 2022, p. 3). His strongly independent character and incredibly distinct work might create a compelling connection for anyone who feels stubbornly out of place.

Similarly, Lucrezia began with an unfortunate story. Her previous husband had left the city of Florence and never returned to her. She met Salvator in 1640 and quickly became his muse and life-long partner. They lived together and had up to six known children but remained unmarried. During their relationship, the church grew less and less tolerant of unmarried couples forming families or living together, which often incurred issues for Rosa, a well-known figure at one point. Rosa faced pressure from the church and the community of Florence, specifically from Pope Alexander VII, to rectify or hide the situation. In response, Rosa arranged for his family to move to Naples in 1656 while he remained between Rome and Florence. This choice is the turning point of Rosa and Lucrezia’s love story. Rosa usually put up an unbeatable, unalterable front. He seemed to do whatever he pleased and however he wanted to behave. However, Salvator altered his usually stubborn attitudes for the safety and security of his lover and children. For the supposed better, he appears to surrender his pride and comfort.

The results, however, are not for the better. While in Naples, a plague epidemic flocks across the city. The remaining Rosa family, originally from Naples, are all taken by the sickness. Rosa’s in-laws, brother, sister, and children all passed; Lucrezia was the lone survivor. They had one more son the following year. Seventeen years later, Salvator and Lucrezia finally married on March 4, 1673. On March 17, Rosa dies, leaving behind very little wealth or possessions. Nonetheless, portraits of Lucrezia still lined his home, such as the Portrait of Lucrezia Paolini (Langdon, 2010).

Viewing Philosophy was more complex than looking at a self-portrait, as Philosophy was never meant to stand alone. Rosa accompanied the work with his muse, Lucrezia, as the form of poetry. Lucrezia in Poetry stands in the light, surrounded by lighter color, and Philosophy now stands alone. In the National Gallery, Philosophy is a lone painting. Across the Atlantic, in the Wadsworth Athenaeum of Connecticut, sits Poetry. To look at Philosophy is to look at Poetry and feel the separation from a world away. Salvator Rosa was a revolutionary artist, a poet, and a philosopher, but he is rarely credited for being romantic.

Salvator Rosa, Poetry, ca. 1640-41, image courtesy of Wadsworth Athenaeum

Rosa himself wrote, “Art does not depict only what is visible but necessarily sometimes alludes to everything that is incorporeal and possible.” The artworks of Philosophy and Poetry accomplish this exactly, whether Rosa meant it to or not. There is forever tension in either painting, knowing the completely complementary yet separated nature. The darkness and silence of Philosophy can only be countered by the brightness of Poetry, which is representative of Rosa and Lucrezia’s own story. Even more so, it presents an all-encompassing human problem — art and thought are not meant to be separated.

Notes:

“Salvator Rosa,” (2024). National Gallery, The National Gallery, Salvator Rosa | Philosophy | NG4680 | National Gallery, London

Langdon, Helen. Salvator Rosa: Paint and Performance (Renaissance Lives). Reaktion Books, 2022. 224 pp. ISBN-13 978-1789145731

Langdon, Helen (with Xavier F. Salomon and Caterina Volpi). Salvator Rosa. Dulwich. Picture Gallery and Kimbell Art Museum in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, London, 2010. 240 pp. ISBN 978-1-907372-01-8