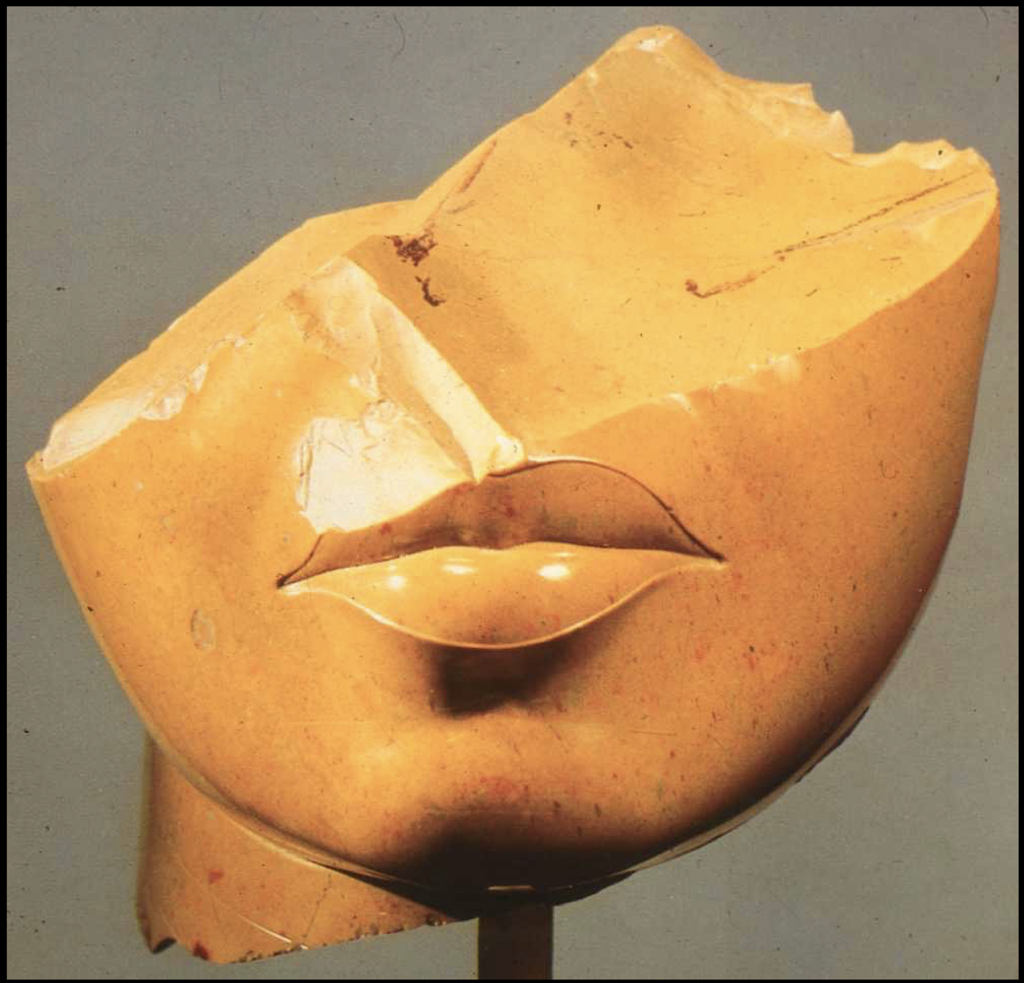

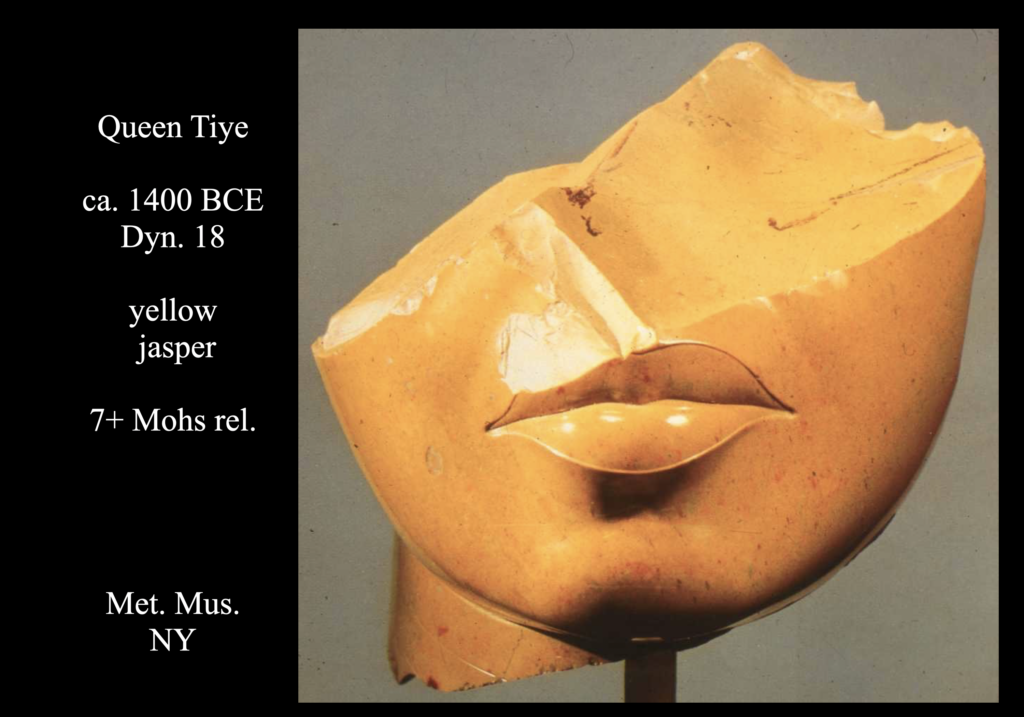

Small fragment (13 cm h) of Queen Tiye bust, yellow jasper, ca. 14th c BCE / Dynasty 18, Metropolitan Museum New York (image courtesy of MMNY)

By Patrick Hunt –

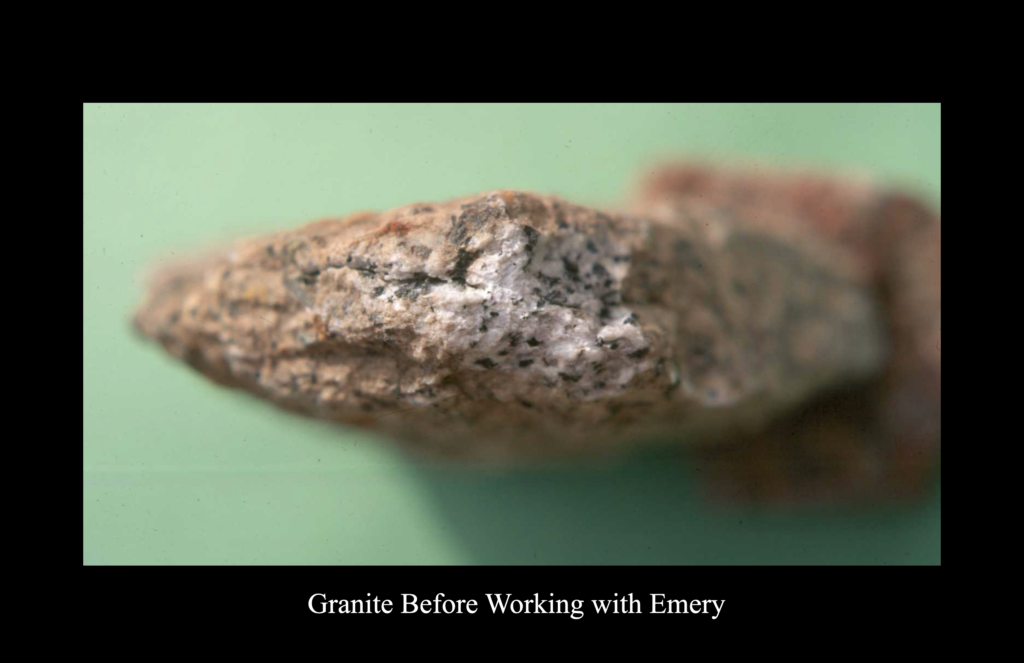

Did the Ancient Egyptians know and use emery? I reprised this old question in 1991 in an invited paper at the British Museum in a November conference “Archaeological Stone: Scientific and Technical Studies” as well as subsequently at an invited seminar lecture for American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) at University of California, Berkeley in January 2000, but a lot of water has passed under the bridge before and after and continuing research has added nuances. It has been a fascinating but contentious debate in Egyptian technology for well over a century around possible Ancient Egyptian use of the very hard stone emery. Emery is also recognized as the geological mineral form of corundite in a non-crystalline form of corundum (basically Al2O3 with a relative Mohs hardness of 9) and sometimes appears with added magnetite (Fe3O4) on Naxos. One of the more slippery items here is trying to understand and estimate hardness in Mohs terms as a relative Mohs number since this is a scratch hardness test for individual minerals that doesn’t easily transfer into heterogeneous rock hardness. Essentially, emery is almost always more heterogeneous than crystalline corundum. Emery from the Aegean island of Naxos – the most prolific source in the Bronze Age – can contain crystalline corundum in the form of sapphire. Emery has been used for millennia as an agent for grinding and polishing hard stone (e.g. granite and quartzite) objects, sculpture in particular; recognized in Rome by Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXXVII, 32: ” …other [precious] stones have to be smoothed with Naxian stone…[emery].”

Many scholars of Egyptology and geologists or geoarchaeologists who work in Egypt or on Egyptian materials have weighed in on the arguments for or against use of emery in Ancient Egypt, [1] and the debate would be without argument if sufficient fragments of emery – any of note – had been found in stone working contexts like quarries primarily or sculpture workshops secondarily where finishing touches were added. But the near complete dearth of extant emery in such contexts for decades has been the loudest argument against much Egyptian use of emery. Despite its advocates, the near complete absence of emery even in remnant stocks of abrasive material has been noticeably remarked, and any argument from silence has not been compelling despite the old borrowed saw that “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence” as we archaeologists and others before us are prone to utter.[2]

Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (45 cm h) (image courtesy of Nelson Atkins Museum of Art)

Emery is notably absent in literature on ancient Egypt: not mentioned in Somers Clarke and R. Englebach, Ancient Egyptian Masonry: The Building Craft, Oxford University Press, 1930, subsequently published as Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture, New York: Dover Press, 1990 although there are copious references to quarrying and hard rocks like granite and quartzite working and dolerite balls in ch. 3 (Quarrying: Hard Rocks), 22-33. Emery is also absent in Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, London: British Museum / New York: Abrams, 1995 although there is an excellent brief discussion on stone and quarrying going back to at least to Pre-Dynastic Egypt with these keen observations: “The carving of stone vessels, often from very hard stones, for funerary use virtually reached the level of mass production in the Early Dynastic Period (3100-2686 BC). By the mid-third millennium BC there were hundreds of quarries scattered across…the deserts…often in extremely remote areas, since the us elf stone was was an essential component of the Pharaonic economy…The amount of quarrying that took place…can be employed as a kind of measure of political centralization and stability. ” [3] Again, emery is absent in Stephen Quirke and Jeffrey Spencer, The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1997 ed., although ch. 7 on Technology gives considerable space to stone-quarrying and related technology. [4] Furthermore, other significant Egyptian stone technology studies also do not mention emery as an abrasive on Egyptian hard stone quarrying or usages including Klemm and Klemm, Malek, Gardiner and others – although they do mention granite and quartzite stone quarrying and use and Gardiner states red quartzite is the “hardest and one of the most beautiful kinds of stone with which the Egyptians ever successfully dealt”.[5]

(Photo P. Hunt, 2022)

Arnold mentions stone tools like dolerite and at least mentions some of the debate about emery, quoting other studies including Shaw but suggests that quantity and sufficient availability does not favor emery. Yet Arnold is skeptical of crushed quartz and sand because the volume of concentric abrasion lines are missing with sand and crushed quartz in experimental use. Shaw also mentions hard stones like basalt and dolerite [6]

(Photos P. Hunt, 2019)

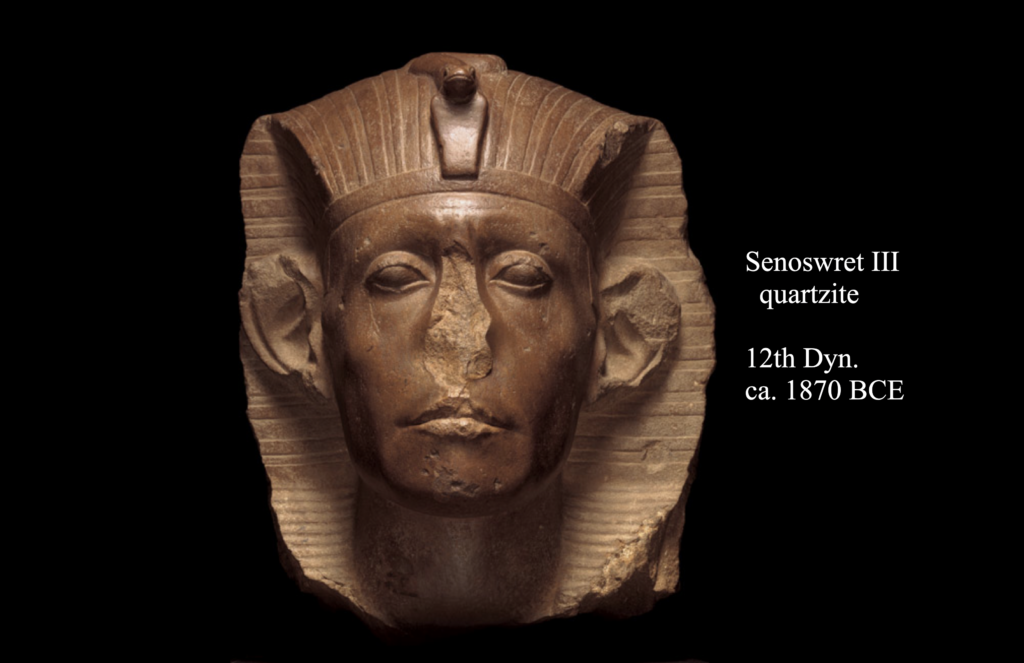

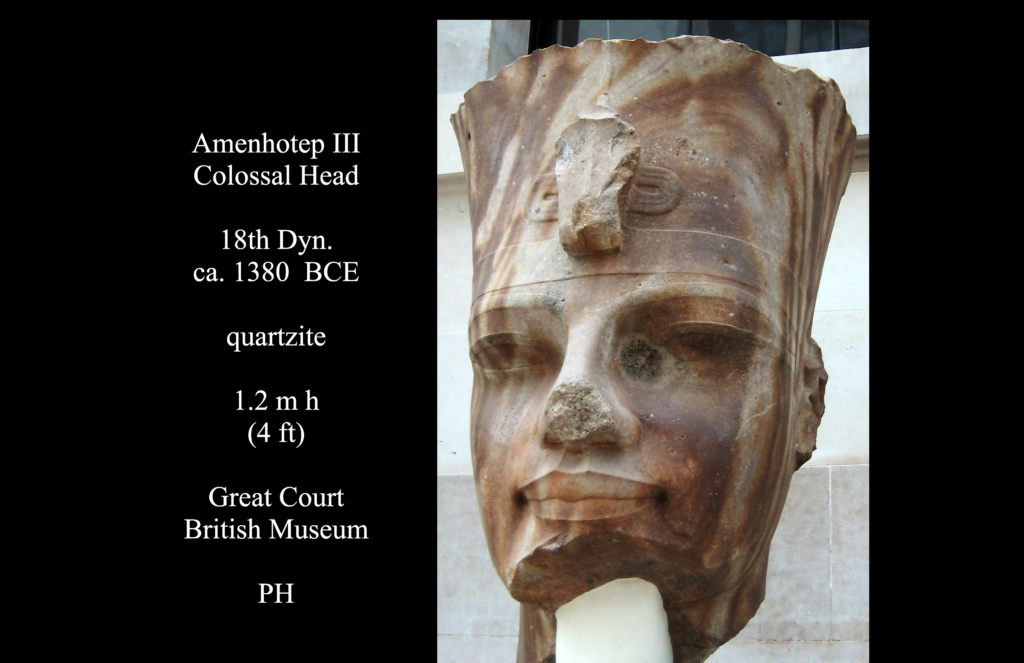

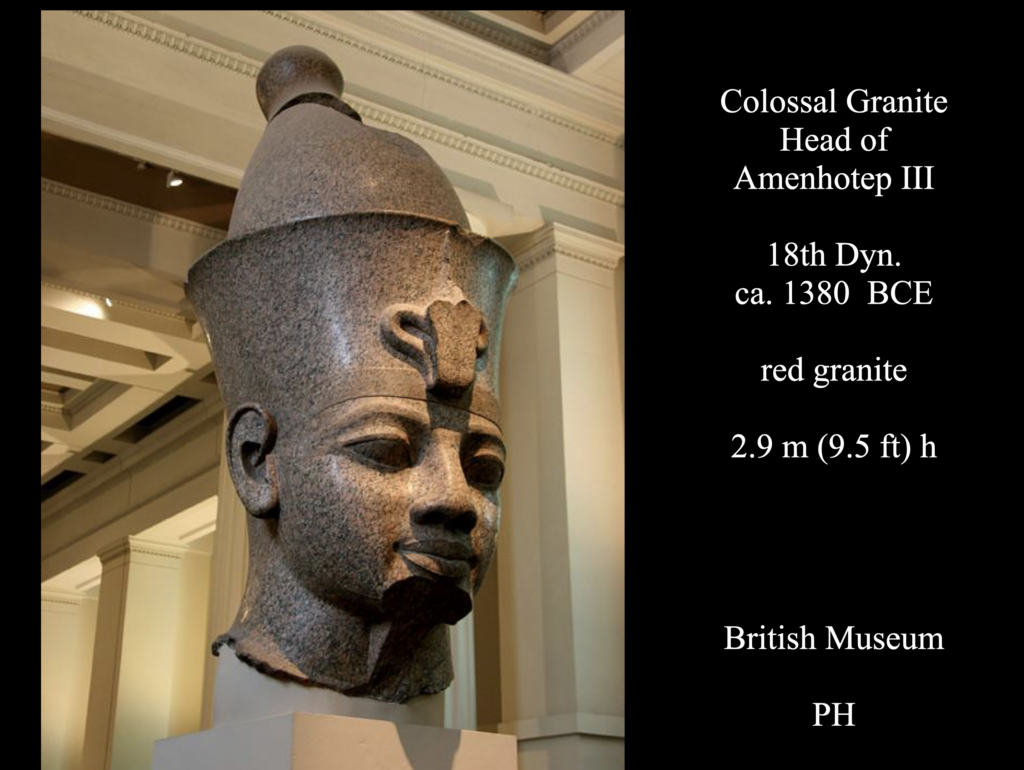

Without mentioning emery as a polishing agent on hard stone in Egypt, Russmann annotates the varied high polish with “glittering smoothness” on the quartzite colossal head of Amenhotep III in the Great Court of the British Museum, a masterpiece of sculpture, like others on Gallery 25 including the pink granite colossal head and polished arm also of Amenhotep III. Such a high polish might also be achieved with quartz sand in a slurry, but emery would be so much easier if used. Given the hardness of quartzite – at least 7 on a relative Mohs scale and harder than granite, the quartz sand as an abrasive would be about as hard as the carved stone whereas emery is significantly harder at around 9 on a relative Mohs scale. [7]

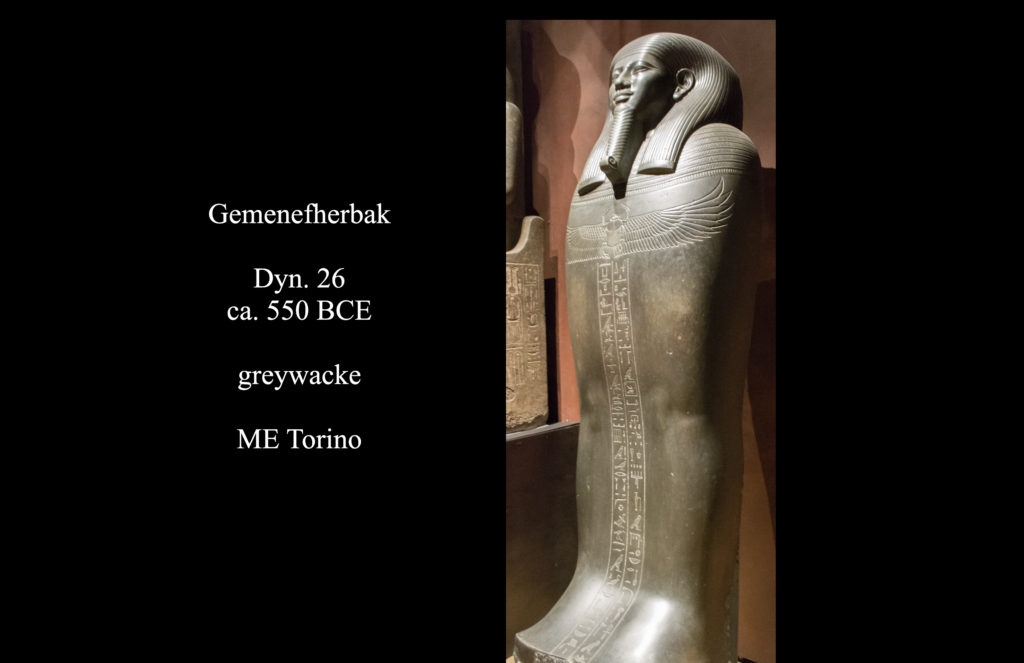

(Museo Egizio Torino, photo P. Hunt, 2023)

Alan Gardiner’s earlier Egyptian Grammar, 3rd ed. Oxford: Griffiths Institute, 1988 reprint, mentions many words for hard stone, including red granite for syenite (m3t), quartzite (rwdt), greywacke (bḫnw) or siltstone, felspar as a hard green (w3ḏ) stone, flint (ds), millstone (bnwt) usually basalt, and other words as an ideogram for hard stone drill in ḥmt and quarryman or hewer of stone (ı͗ky) as well as precious hard stones like carnelian (ḥrst), jasper (mḫnt), turquoise (mfk3t or mfkt), amethyst (ḥsmm), malachite (šsmt) and even lapis lazuli (ḫsbd). These extant Egyptian words by the Middle Egyptian period for various stones and stone industry, evidence of a nascent empirical recognition of geological differences, but emery is not mentioned in Gardiner’s Egyptian glossary.[8]

(Image courtesy of Boston Museum of Fine Arts)

Yet Flinders Petrie states in the 1910 edition of his The Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt: “As far back as prehistoric times, blocks of emery were used for grinding beads, and even a plummet and a vase were cut out of emery rock (now in University College [London]). There can be no doubt, therefore, of emery being known and used.” p. 72. Not many have agreed with Flinders Petrie, and having been many times in the Petrie Museum at University College London, I can attest the above emery artifact he mentions is not easy to find among 80,000 objects both on display and not on display.[9] Has more modern study superseded Flinders Petrie?

Lukas clearly disagreed with Petrie, and “rejected the use of emery, an impure variety of corundum, as there is no evidence of its occurrence in Egypt.” [10] Stocks adds “the lack of emery in Egypt…”, [vis-a-vis] “…the existence of desert sand in vast quantities…the finding of sand powders… and experimental evidence…that sand will grind very hard stones” compound the problem of over-stating emery’s use.[11]

Gorelick and Gwinnett resolve some of the abrasive argument between Petrie and Lukas, finding that emery could have been used but with more detail than Petrie and Lukas provide. [12]

Other early 20th century Egyptologist advocates for emery used in Egypt have included Ludwig Borchardt – finder of the controversial but famous Nefertiti bust at Amarna now in the Neues Museum Berlin- in Baugeschichte des Amontempels von Karnak. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1905, as well as George Reisner in Mycerinus, the Temples of the Third Pyramid at Giza. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931, among others. More recently, Aston, Harrell and Shaw in Cambridge’s Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology 2009 (see note 1) state “both the drills and wires achieved their effect by combination with quartz sand and emery abrasives,” acknowledging the abundant use of sand but adding emery as an abrasive as well. [13] Since Harrell is a geologist by training, where most others noted are not, this lends significant credibility to the emery use argument. Harrell is also the pioneering geologist who has conducted the definitive study of the Turin Papyrus, [14] combined with a geological survey of the Eastern Desert and Wadi Hammamat. The Turin Papyrus is the oldest geological map in existence (ca. 12th c. BCE) especially on the auriferous Wadi Hammamat with identified bekhen (or bḫnw) greywacke-siltstone stone and quartz in a tour-de-force of nascent Egyptian geology at the Museo Egizio in Torino. I have seen and studied this map many times in Torino, most recently several times (2021, 2023) with Cedric Gobeil, Curator and Conservator at Museo Egizio and Director of the French archaeological mission of Deir el-Medina (IFAO) and former Director of the Egyptian Exploration Society (2016-19). [15]

Because my own doctoral work was in archaeological science and focused on volcanic stone provenance, weathering and technology at the Institute of Archaeology UCL University College London (Ph.D. 1991), I had considered the use of emery as a stone working material for years prior to and pursuant to my graduate work. In process, after a minor in physical science taking multiple geology courses among other sciences, I had two internships at the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California in Igneous and Geothermal Processes conducting petrography as well as interning at the USGS Radiocarbon Lab. At UCL I also further studied petrography and spent considerable time at the nearby British Museum, where I became acquainted with Carol Andrews in the Department of Egyptian Antiquities, who asked me to examine many of the stone Egyptian amulets. I frequently noted the high polish on Egyptian sculpture of granite and syenite and knew the logical arguments for abundant quartz sand as an abrasive. Carol Andrews and I had conversations about emery which I usually brought up and she confirmed its Greek word etymology as smúris (σμύρις) or alternatively smíris (σμίρις) [16] but said it would be difficult to evidence in Ancient Egypt before the Hellenistic Ptolemaic presence. Indeed its etymology exists into the Later Roman Patristic Era as smyrítes (σμυρίτης) in Patristic Greek. [17]

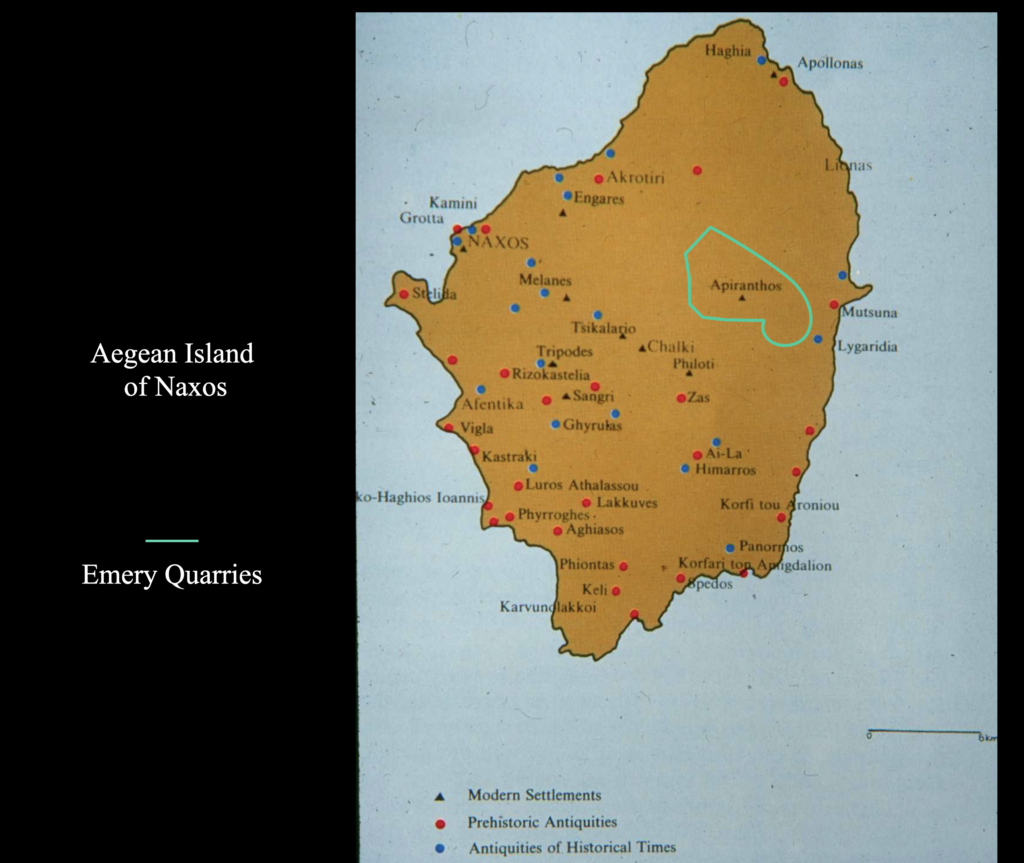

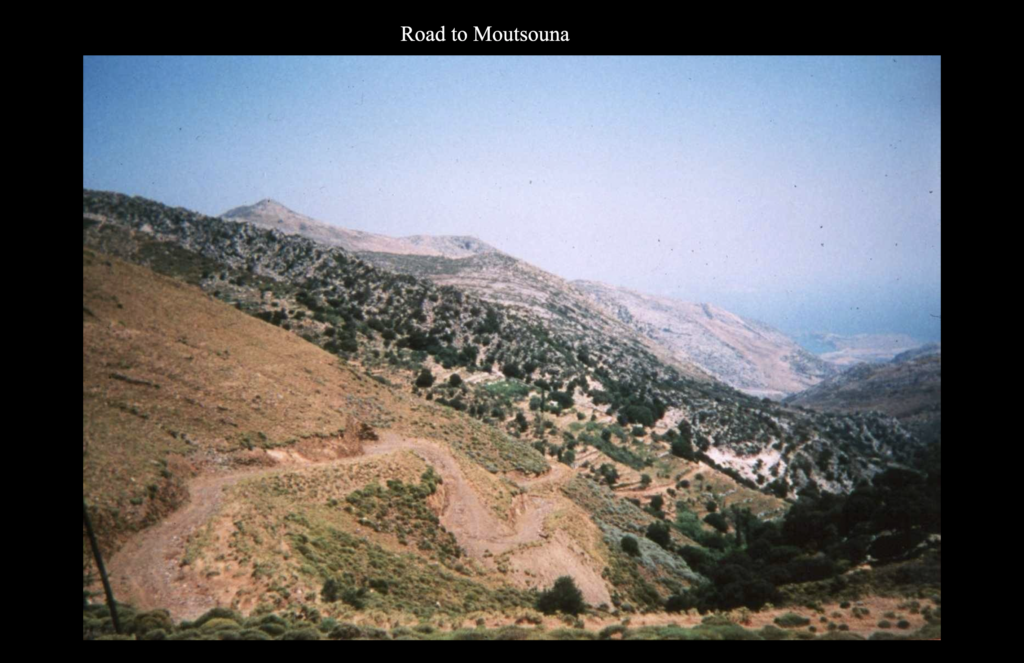

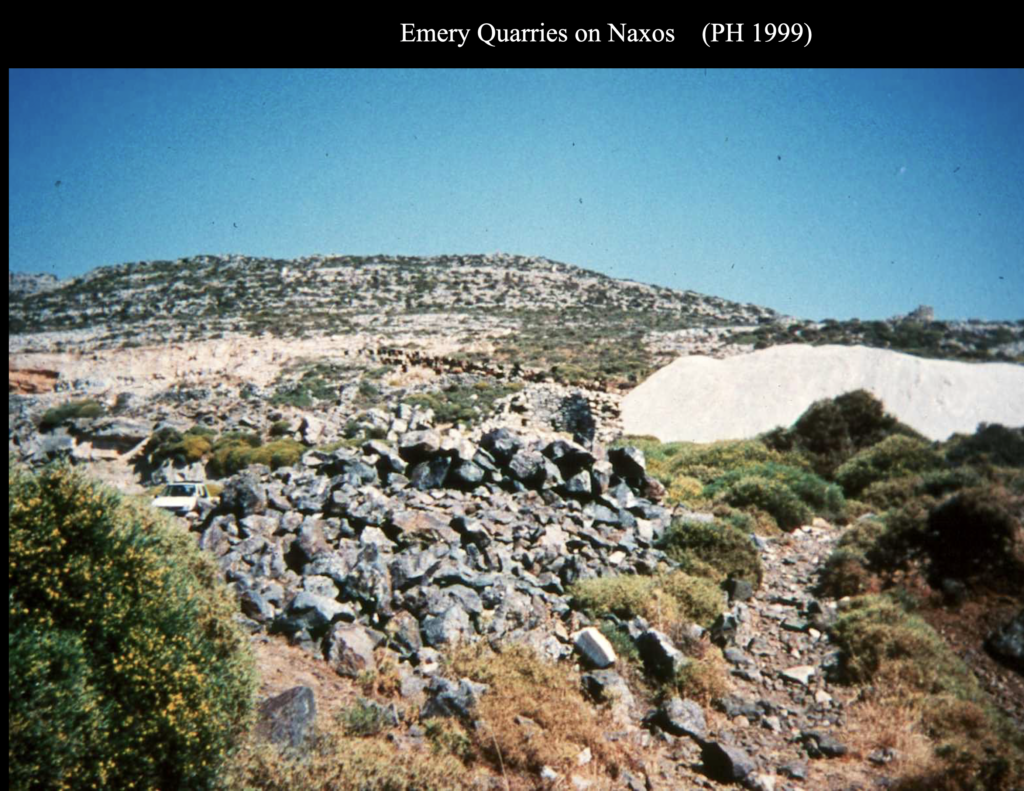

So when Vassilis Lambrinoudakis (then Professor of Classical Archaeology at University of Athens) invited me to the island of Naxos in the mid 1990’s, I was able to see Naxos in a detailed survey especially of its emery mining region around Apiranthos and visited several emery quarries, both ancient and modern, as well as drove the ancient road down the eastern slope to above the ancient harbor of Mutsuna, active there since the Bronze Age and still used to day for modern emery export. With permission I was able to acquire emery samples around the quarries for petrographic and experimental technology research. About the same time I had also been invited by Christos Doumas, Excavator of Akrotiri / Director of Antiquities on Thera / Santorini to stay at ancient Akrotiri, where I noted large basalt vessels in the storage depots from the Late Bronze Age, and seriously considered the use of local emery from nearby Naxos as a shaping and polishing agent. When I was a postdoctoral research fellow (1992-94) in Near Eastern Studies at University of California, Berkeley, I had good conversions on emery with Wolfgang Heimpel there, whose team had already found and published on Armenian emery as an abrasive and sometimes known as šammu (shammu) in Bronze Age Mesopotamia.[18]

Naxos emery quarries and Eastern road to Mutsuna (Moutsouna), Photos P. Hunt 1999

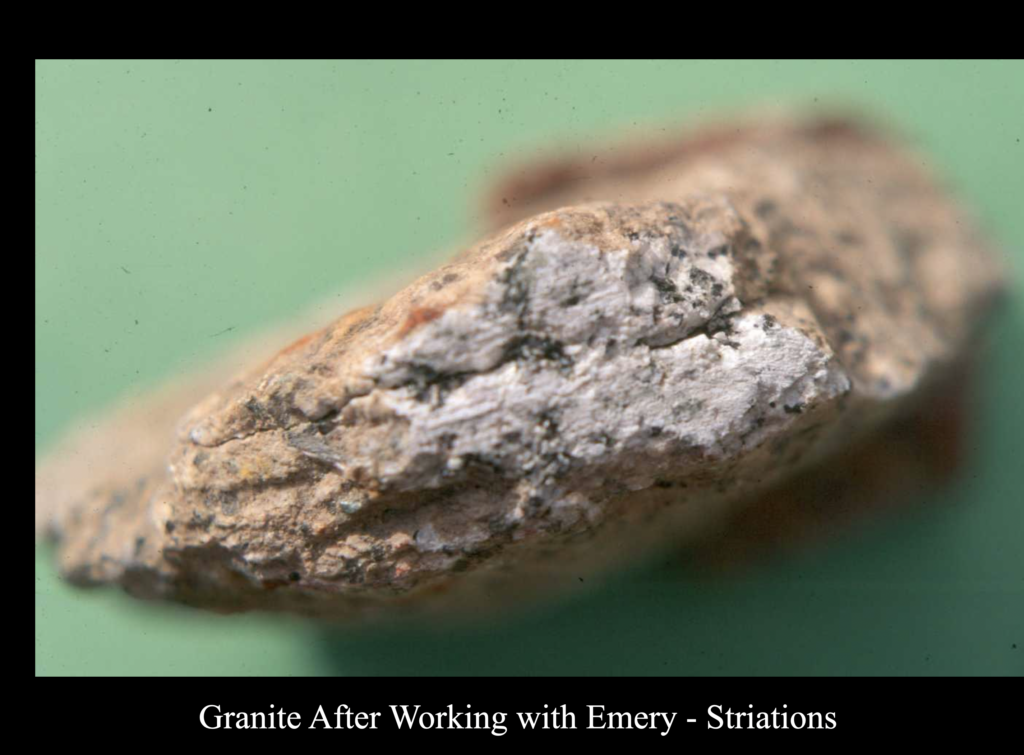

I found that my Naxian emery samples easily worked different granites, removing considerable material into a pulverized powder when dry or as a slurry with water even with little effort on my part in grinding granite with my emery samples; easier when wet but nearly as effective even when dry. I was easily able to remove 1 gram or more of granite every 30 seconds with emery samples. My initial weight and mass tests also showed that with a near equal volume of ~60 mm in length, ~35 mm in depth and ~50 mm in width for both muscovite granite and red granite and about the same for emery, the mass / weight difference was substantial: the Naxian emery was much denser than the granites and weighed more at 249.476 grams than both granite samples together at 235.301 grams. I also tried abrading this Naxian emery on the side of a steel file, which easily removed the rounded side ridges into a squared edge by grinding off at least ~1mm with minimal effort. To date I haven’t published any of these experimental studies which require more substantial scientific verification in a more controlled context environment.

(Emery and Abrasion Studies, photos P. Hunt 2002)

A newer development came in 2003 while perusing Thutmose III’s Annals. There his import lists from various campaigns over decades ca.1458 -1438 BCE are recorded on the Karnak Temple of Amun. In his Annals I came across a word that appeared to be spelled ysmerii for an imported stone and immediately wondered if it could be emery. This was earlier noted in line 15 of the fragment Lepsius published in Denkmaeler Abteilungen aus Aegypten und Aethiopien III. Bl. 30a that Samuel Birch published when Asst. Keeper of the Dept. of Egyptian Antiquity of the British Museum in his Thutmose Annals commentary. [19] There was no question that Thutmose had dealings and trade relationships with the Aegean cultures, e.g., note the travertine (alabaster) amphora with a Thutmose cartouche found at Katsambas, Crete, published by Karetsou.[20] It is also well-known that it was a two-way trade because Minoans are also shown on Egyptian tomb paintings, e.g. Tomb of Rekhmire (TT100) ca. 1479-1400 BCE (about the same time as Thutmose III), bringing trade and other objects when Egypt knew Crete as Kftjw or Keftiu. Egypt also knew “Keftiu and the [Aegean] Islands” as kftjw jww ḥrj-jb nw in the middle of the “Great Green Sea” (w3ḏ wr). [21] Since ancient Akrotiri on Thera had a port – now buried under ash from the massive volcanic eruption ca. 1620 BCE – that plied the Cycladic Island waters assumably with Naxos, since the Bronze Age harbor of Mutsuna is the export center on the Naxos island’s northeastern side (and was present even in prehistoric times), it wasn’t so speculative that trade with earlier Minoans and later cultures could have easily provided emery for stoneworking, including to Egypt. I published this ysmerii listing in 2007 in a chapter on Thera and its contributions as a major Cycladic island hub for Minoan trade.[22] What is moot, however, is possible earlier trade between Egypt and the Aegean going back into Predynastic periods. The question of how early could emery have been imported into Egypt is beyond the scope of this paper, but is nonetheless a valid enquiry given the abundance of highly-polished Nagada II-III diorite vessels as early as mid-4th millennium. One incredible artifact, the shattered yet beautiful small (13 cm high) yellow jasper bust of Dynasty XVIII’s Queen Tiye – wife of Amenhotep III – at the Metropolitan Museum New York (featured lead image above) illustrates such a high reflective polish that suggests to me the possible use of emery abrasive as a polishing agent.

(Image courtesy of MMNY)

Anna Serotta has also published one of the best, most relevant papers on Egyptian stone working tools, in some cases summarizing prior work but also synthesizing some of her own experimental processes and she does include a silicified sandstone (quartzite) grinding stone from Dynasty 19 (Ramesside) at the Metropolitan Museum New York.[23] In general, softer stones could be carved and inscribed with harder stones, as we also found with extant quartzite hammer stones at the andesite quarries of Rumiqolqa, Peru when I worked there in 1988 with with Jean-Pierre Protzen was this was one of the very questions we were addressing there.[24] But I remain unsatisfied as to what exact tools were used in Egypt, for example, to carve hieroglyph inscriptions in very hard stone. Serotta also states the necessity of hard percussive stone tools including flint, essentially hard silica. Despite never having been found even as detritus or in debitage fragments, I remain curious as to whether small emery chisels or emery flakes could have also been used to carve inscriptions in very hard stone, but this is unfortunately another argument from silence.

For me personally, the emery abrasive clincher came in 2015 when the above-mentioned Anna Serotta at the Metropolitan Museum New York published her analytical report finding abundant emery (corundum) powder residue in an indurated limestone fragment (from Amarna, Late Dynasty 18, mid-14th c. BCE) with a broken tubular drill core using SEM+EDS with X-ray spectroscopy, as shown in her multiple images. Serotta also summarizes the long debate about Egyptian use of emery with clarity and accuracy as expected of a scientist.[25] Even though this might appear to be only a one-off and not normative, the emery abrasive dam has broken after much contentious debate.

Reading Serotta’s report, I felt vindicated after decades of being challenged by quite a few otherwise reasonable scholars about possible Egyptian use of emery, even though the abundant use of quartz sand may have been in much greater volume as a normative abrasive. I suspect Naxian emery has possibly been imported and used in Egypt since Predynastic Nagada I-III periods for over five millennia on diorite vessels even given the dearth of extant Egyptian tools and other abrasive finds in Egypt. In multiple postgraduate courses at Stanford on Egypt, I have pointed out the possibility of very early emery use; now some of my postgrad students are asking the same questions on their own without being led there. I also wonder if the long but elusive use of abrasives for obvious high polish on so many very hard stone Egyptian artifacts – especially gneiss, granite, greywacke and quartzite – and sculptures has perhaps silently argued better than I can about imported emery in Ancient Egypt.

(Image courtesy of Field Museum Chicago)

Notes:

[1] W. M. Flinders Petrie, The Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt. Edinburgh: Thomas Noble Foulis, 1910 ed., 72, 73, 81, esp. 72; A. Lukas, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. 4th rev. ed. London: E. Arnold and Mineola (Dover Books, 1962) 66-67; L. Gorelick and A. J. Gwinnett, “Ancient Egyptian Stone Drilling:” Expedition [Magazine] 25.3 (1983) (U. Penn), 40-47; Barbara Aston, James Harrell, Ian Shaw, “Stone” ch. 2 in Paul Nicholson and Ian Shaw, eds., Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009, 65; Denys Stocks. Experiments in Egyptian Archaeology: Stoneworking Technology in Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge (2015) 109 & ff. These sources are elaborated in following notes.

[2] While cosmologists Martin Rees and Carl Sagan popularized this idea in the 20th century, it can be likely traced back to at least the end of the 19th century in Hittitology (1887) by W. Wright “The Empire of the Hittites” at the London Victoria Institute (Philosophical Society of Great Britain vol. 21) and in geology (1895) by W. J. Sollas in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London vol. 51 on glaciology.

[3] Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, London: British Museum / New York: Abrams, 1995, 279-70.

[4] Stephen Quirke and Jeffrey Spencer, The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1997 ed., ch. 7 “Technology”, 164-66 & ff.

[5] Rosemarie and Dietrich Klemm, Stone and Quarries in Ancient Egypt, London: British Museum press, 2009, 236, 321, etc. yet mention dolerite hand stones; Jaromir Malek, In the Shadow of the Pyramids: Egypt During the Old Kingdom, London: Orbis / Little, Brown / Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1986, 58-9; Alan Gardiner. The Egyptians. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961, 37-8;

[6] Dieter Arnold. Building in Egypt: Pharaonic Stone Masonry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, dolerite 37, 40, 48 and ch. 6 Tools and Their Application” also including dolerite 260, 263 and emery 265; Ian Shaw, “Pharaonic Quarrying and Mining Settlement and Procurement in Egypt’s Marginal Regions.” Antiquity 68.258 (1994) 108-19, esp. basalt and dolerite (116). Elsewhere Shaw mentions precious stone (amethyst) mining in Ian Shaw and R. Jameson .“Amethyst mining in the Eastern Desert: A Preliminary Survey at Wadi el-Hudi.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79 (1993) 81-97.

[7] E. R. Russmann, ed. Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum. Berkeley: University of California Press / with American Federation of Arts, 2001, 132.

[8] Alan Gardiner. Egyptian Grammar, 3rd. ed. Oxford: Griffiths Institute, 1988 repr., 518, 555, 560, 564, 567, 568, 577, 582, 585, 586, 595, 603.

[9] Alice Stevenson. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections. London: UCL Press, 2015.

[10] Denys Stocks. Experiments in Egyptian Archaeology: Stoneworking Technology in Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge (2015) 109 & ff..

[11] Stocks, 111.

[12] (mentioned in note [1]), Leonard Gorelick and A. John Gwinnett, “Ancient Egyptian Stone Drilling:” Expedition [Magazine] 25.3 (1983) (U. Penn), 40-47, esp. 45& ff. comparing the effects of these abrasives under SEM micrographs.

[13] Alan Millard. “Cartography in the ancient Near East.” The History of Cartography. Volume 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. J. B. Harley and D. Woodward, eds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. 107-116.

[14] Harrell, J. A. and V. M. Brown. “The oldest surviving topographical map from ancient Egypt (Turin Papyri 1879, 1899 and 1969).” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 29 (1992) 81-105; also James Harrell, “Turin Papyrus Map from Ancient Egypt” (http://www.eeescience.utoledo.edu/faculty/harrell/egypt/turin papyrus/harrell_papyrus_map_text.htm); also James A. Harrell and V. Max Brown, “The World’s Oldest Surviving Geological Map: The 1150 B.C. Turin Papyrus from Egypt.” Journal of Geology 100.1 (1992) 3-18.

[15] Patrick Hunt. “Turin’s Egyptian Museum.” Electrum Magazine, August 2012 (https://www.electrummagazine.com/2012/08/turins-egyptian-museum/).

[16] H. G. Liddell and R. Scott. Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996 ed., 1620.

[17] G. W. E. Lampe. A Patristic Greek Lexicon, Fascicle 5. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968,1244.

[18] W. Heimpel, L. Gorelick and A. John Gwinnett. “Philological and Archaeological Evidence for the Use of Emery in the Bronze Age Near East.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 40.2 (1988) 195-210.

[19] Samuel Birch. The Annals of Thothmes the Third as Derived from the Hieroglyphical Inscriptions. London: J. B. Nichols and Sons, 1853, 22 note a.; also p. 49 and fig. 100.

[20] Alexandra Karetsou, ed. Kρήτη-Αίγυπτος: Πολιτισμικοί Δεσμοί Τριών Χιλιετιών, Κατάλογος (Crete-Egypt: Cultural Ties of Three Millennia: Catalog/Directory) Athens: Kapon Editions, 2000, cat #219.

[21] J. D. S. Pendlebury. “Egypt and the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 16.1/2 (1930) 75-92; R. S. Merrillees, “Aegean Bronze Age Relations with Egypt.” American Journal of Archaeology 76.3 (1972) 281-94; Keith Branigan. “Minoan Colonialism” Annual of the British School at Athens 76 (1981) 23-33; H. Matthäus. “Representations of Keftiu in Egyptian Tombs and the Absolute Chronology of the Aegean Late Bronze Age.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 40 (1995) 177-94; Carl Knappett, Irene Nikolapoulou. “Colonialism without Colonies: A Bronze Age Case Study from Akrotiri, Thera.” Hesperia 77 (2008) 1-42; Uroš Matić. “Memories into Images: Aegean and Aegean-like Objects in New Kingdom Egyptian Theban Tombs.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 29.4 (2019) 653-69.

[22] Patrick Hunt. Ten Discoveries That Rewrote History. New York: Penguin Group, 2007, ch. 8, 178-80.

[23] Anna Serotta. “Reading Tool Marks on Egyptian Stone Sculpture.” Revista del Museo Egizio December 2023 (https://rivista.museoegizio.it/article/reading-tool-marks-on-egyptian-stone-sculpture/).

[24] Patrick Hunt. Provenance, Weathering and Technology of Selected Archaeological Basalts and Andesites. Ph.D. Dissertation, 1991, Institute of Archaeology London, UCL. Ch. is on Inca and Andean stone procurement, technology,weathering and related topics. Also see P. Hunt, “Inca Volcanic Stone Provenance in the Cuzco Province, Peru.” Papers of the Institute of Archaeology 1.1 (1990) 24-36.

[25] Anna Serotta with Federico Carò. “Hidden Secrets of Ancient Egyptian Technology.” Metropolitan Museum New York, May 22, 2015, online article (https://www.metmuseum.org/articles/ancient-egyptian-technology#4); also in Horizon 14, the Amarna Project and Amarna Trust Newsletter, Spring 2015. but unavailable.