By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

A day at the National Prado Museum in Madrid is never enough, but there are always my landmark works of art to see when there. More Titians than one can easily count, and the Velazquez portraits are a Spanish Baroque force majeur, and the Goya Gallery is mesmerizing, but perhaps above all the Bruegel and Bosch Gallery is always astonishing. Following here are a few of my individual favorites. When we lived in London, I worked for Phillips Auctioneers on New Bond Street but we loved short hops over to the Continent to visit national museums.

First, although Titian’s portraits of the Habsburgs are both intimate and powerful, it is his mythological paintings that intrigue me most, especially the ones for Alfonso d’Este’s renowned Ferrara Camerino showcase room. His The Worship of Venus (ca. 1518) has a whole hyperactive crowd of playful putti and even more frenetic is the bacchanal of The Andrians (ca. 1524), which is over the top with much wine flowing in contrast to supine gods in front of a dramatic landscape.

In The Worship of Venus, the fluffy blue or brown wings of the putti under the statue of Venus are hardly big enough for flight, but the marble statue of Venus is the only persona who can bring calm to this divine nursery.

Then there is Titian’s wonderful Danaë and the Shower of Gold (ca. 1562), where the nude Danaë imprisoned by her father in a sealed room was desired by Zeus, who found a way inside the chamber (and also inside her) coming as a shower of golden light through a narrow overhead slot – often portrayed as a shower of golden coins as here gathered up by her old nurse in the one possible tunic she’s not wearing. This myth retold by Ovid also later inspired both Rembrandt and apparently Klimt who followed Titian’s rendition in different ways.

Second, speaking of Habsburgs, Diego Velázquez lived in the palace of Philip IV for decades, taking a lot of time to paint the royal family, so no wonder his 1653 portrait of this famous king with the “Habsburg chin” is one of his best: a chiaroscuro gem of realism with its nearly black-brown background behind the pale king dressed in black. Philip’s huge waxed pointy mustache curving half way up his face seem to want to touch his tired but luminous eyes framed by his golden curls; his lace collar sets the white-on-black contrast so well that his penetrating eyes are clearly the most lively element of this famous portrait.

Third, who can ever tire of Francisco de Goya’s revolutionary and tragic Third of May 1808 or his macabre Saturn Devouring His Son ca. 1821. Goya’s Third of May 1808 has to be one of the most dramatic paintings in the world with its – again – chiaroscuro night sky and the lantern between the lineup of men about to die and the faceless gray firing squad lights up the aghast man in the middle with his white shirt and arms extended like Christ waiting for the imminent bullets that are about to shred his body. We cannot help but weep with the other revolutionaries in this incredible picture of abject pathos against Napoleonic violence, especially with the church tower on the dim skyline – is it suggesting national complicity or merely institutional contradiction?

Of Saturn, all we can conclude is that his future is as irrational as his present crazy-eyed mindlessness and his horrific awkwardly-flailing body is in contrast to the immobile symmetry of the body of the son being devoured – actually swallowed whole in the Classical myth but Goya’s sensational hyperbole accentuates the defiling ungodliness of Saturn here.

Last but not least, the mind-boggling art in the incredible Bruegel and Bosch Gallery will hardly let you walk away in less than an hour because of the astonishing originality and relevance of these unique artists whose world views bordered on that ambiguous place where allegory and irony mingle. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ca. 1562 Triumph of Death is a startling reminder how plague and global pandemic – never really very far from us – looked in the late Medieval and early Renaissance world with rampant death invading every possible nook and cranny of life. The marching army of Death appears unstoppable and far outnumbering the living. In the painting anyone ignoring death must be naive and foolish because death reaches a skeletal hand unto their shrinking space even if not yet their consciousness. None are safe: a king in the bottom left corner, serenading lovers in the bottom right corner all face a bleak landscape where life grows hopeless whether they know it or not. This painting may be too close to home for many still reeling from our own pandemic, especially those who have lost friends and loved ones.

Likewise, Bruegel’s ca. 1567 The Wine of St. Martin’s Day – not viewed here – is a study in chaos bright about by a moral conundrum of gluttony and how hedonism can take pleasure too far, and also how wine both elevates in moderation and stupefies in immoderation.

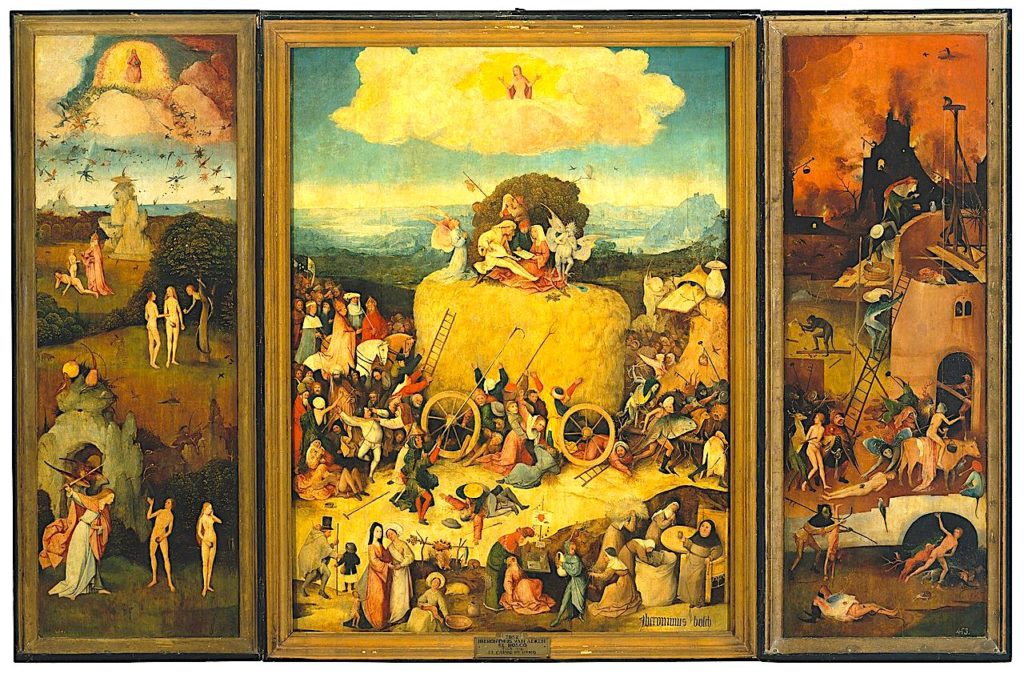

Slightly earlier, Hieronymus Bosch’s clever landscapes like The Haywain of 1515 animate Flemish proverbs such as “The world is like a hay cart and everyone takes what he can…” Actually a triptych with Creation and the Garden of Eden on the left and Hell on the right, above the central panel Christ views the results of unchecked desire leading to sin by showing the wounds of his Passion, a much-needed balancing act between heaven and earth.

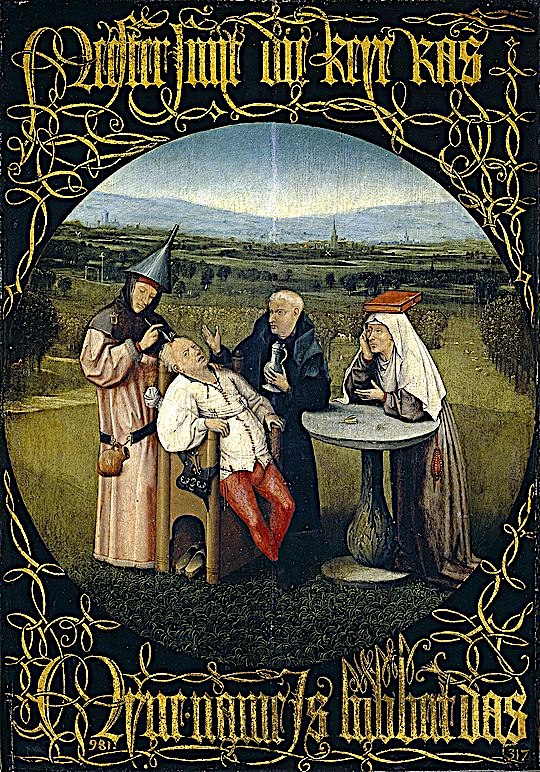

Satire reigns as well in Bosch’s ca. 1500 Extraction of the Stone of Madness where medical quacks and fraudulent priests exploit stupidity with misinformation and science and books are either ignored or not even consulted, again eerily relevant to our own time. Not viewed here, Bosch’s famous ca. 1502 Garden of Earthly Delights requires patience both with the curious crowds and all the mysteries of its strange imagined scenes and its intellectual cornucopia of imaginary possibilities from the Fall of Man to Paradise however allegorized.

But my favorite is Bosch’s timeless and elegant 1494 Adoration of the Magi where the richly-dressed Magi showcase the wide world in general from their different continents and their three ages of humanity as they bring wondrous gifts before the Holy Family that deserve our full scrutiny as well: even the details of their garments, especially the silvered middle Magi’s tunic bears a story within a story – who knows what allegories are still hidden in this painting? – of historic narrative and likewise nearly every other detail beggars the imagination in this quiet masterpiece of extended Nativity.

This triptych with patrons (Peeter Scheyfve and Agnes de Gramme, identified by their heraldry on their adjacent panels on the left and right) with their namesake saints (St. Peter and St. Agnes) has unusual personal and topographical details that cannot always be easily identified with certainty, but the painting otherwise follows the formulaic necessities of this vignette combining biblical legendary narratives. Following these wise Magi of Bosch, at least a day’s visit to the Prado with the museum’s The Prado Guide (Museo del Prado 200 Años) should always be your wise gift to yourself when in Madrid.

The Prado Guide. Museo Nacional del Prado, 2022 ed.