By Patrick Hunt –

Olaf Tryggvason

Olaf I Tryggvason (ca. 960-1000 CE) was the Viking king who forcibly began to Christianize the people of Norway at the end of the 10th century, a change suggested at times by his detractors as conversion forced at swordpoint. If depicted as a bloody enforcer against Norse paganism rather than a gentle persuader, he was ultimately killed in fierce battle with other Vikings who resisted conversion. Some later sagas claim he was the great-grandson of Harald Fairhair (ca. 850-932 CE), the first king of Norway, as well as the founder of the city of Trondheim in 997 CE close to where the Nid River eventually rounded the peninsula on which the Viking city grew and where the later cathedral stood. Olaf I Tryggvason was defeated in the Viking naval Battle of Svolder but seemingly jumped off his ship onto the sea and was seemingly never seen again after a suicide drowning, although legends say he might have surfaced elsewhere around the Baltic.

St. Olaf Haraldsson

Olaf I Tryggvason’s Christian successor after a generation of briefly-reigning kings like Seven Forkbeard was Olaf II Haraldsson (995-1030 CE) who reigned from ca. 1015 to his battlefield death. Some Icelandic sagas attest that Olaf II was a great-great grandson of Harald Fairhair, thus also related to Olaf I Tryggvason by another lineage. Olaf II was formally credited with formalizing the glimmers of Christianity begun by his possibly namesake predecessor Olaf I into a systematic Norwegian religion. His death defending the new religion was followed by purported miracles after the Battle of Stiklestad, and he was canonized as St. Olaf by the Roman Catholic Church in Norway and elsewhere where his hagiography spread after his legendary internment. One such miracle around his tomb but lacking credible documentation was that a blind man’s sight was returned after time spent where Olaf was temporarily interred at the Battle of Stiklestad or possibly in Trondheim in the older Church of St. Clement before the cathedral was erected, but early sources do not agree on details. Another legend is that when reinterred in Nidaros, his hair and fingernails had kept growing – actually not uncommon in a corpse – but for a considerably long time. Other observation tales weave incorruptibility of his body into a saintly hagiography. Pope Alexander III later confirmed Olaf’s canonization in 1164. Olaf II Haraldson has been named Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae, “eternal king of Norway” since the 1200’s. The 12th century text Passio a miracule beati Olaui (Passion and Miracles of the Blessed Olafr) is the source of many legends about Olaf.

Eventually the remains of Olaf II’s body were brought back from Stiklestad to Trondheim for burial around 1030, possibly first claimed in the older Church of St. Clement and then reinterred in what would ultimately become the site of the northernmost Gothic expression in Nidaros Cathedral. His exact burial spot, however, is debated and cannot yet be confirmed in the various crypts somewhere under or near the cathedral altar.

To date Trondheim archaeologists in Nidaros Cathedral have searched many sarcophagi and skeletal remains but nothing definitive has yet been found to match his known body measurements and relatively short stature, although he was also said to be stout for his short size. It is likely that any memory of Olaf’s exact grave was lost since the Reformation around 1536 with the establishment of the Lutheran church, exile of the Catholic Archbishop and multiple burnings and collapse of much of the original Romanesque cathedral, as it remained in ruins for about three subsequent centuries until Norway’s independence.

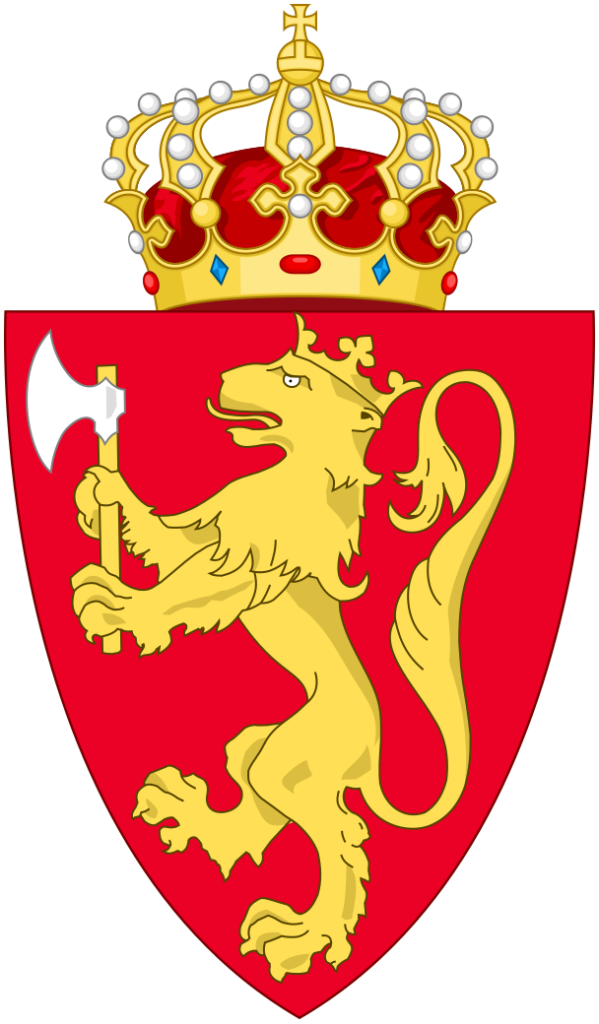

King St. Olaf Heraldry with His Axe

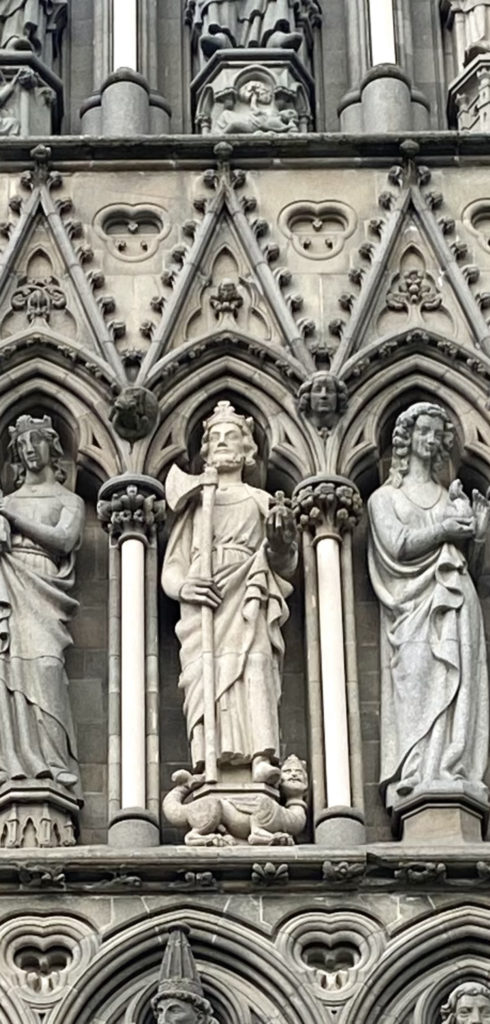

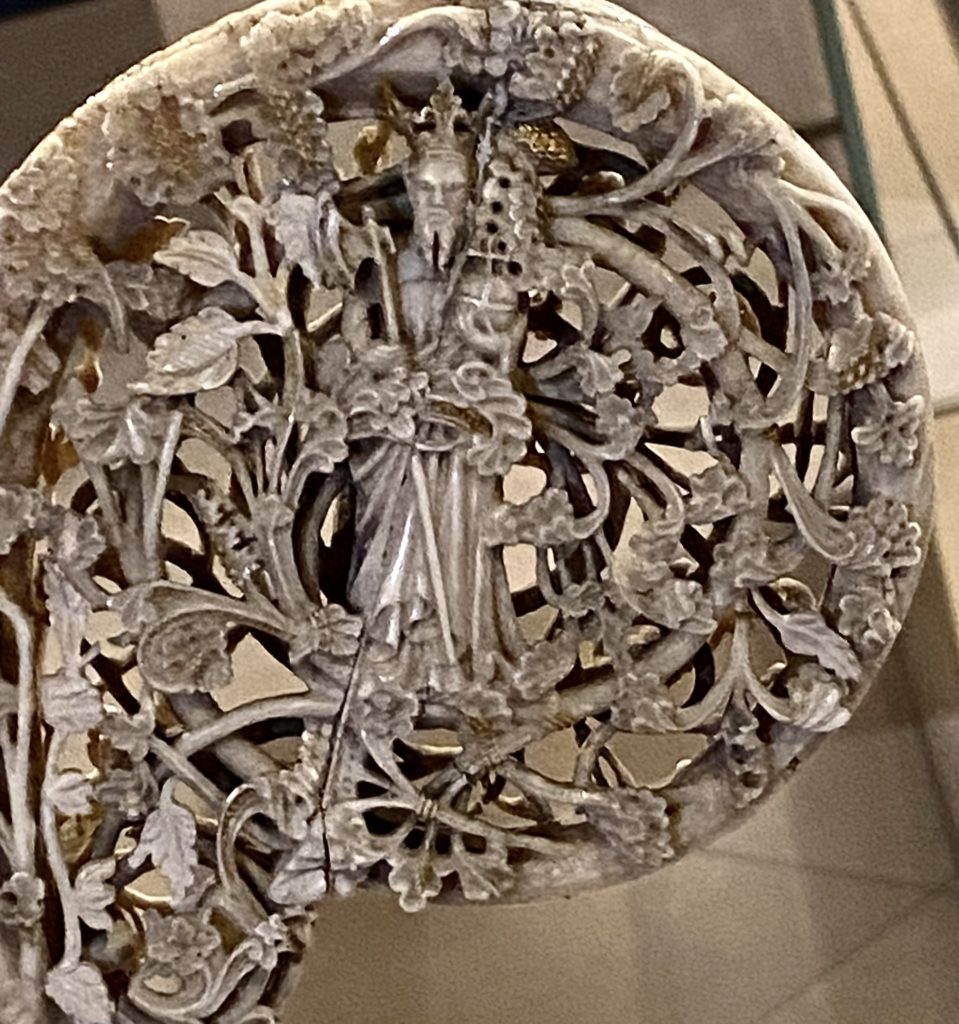

Olaf II’s heraldic iconology is universally associated with a Viking-style axe – even the royal pennant of Norway and the Royal Coat of Arms with a golden lion on a red field (gules, a lion rampant or) holds this silver axe – and this is seen in nearly every formal depiction, including in his statue on the facade of Trondheim Nidaros Cathedral.

A 14th c. ivory bishop’s foliated crozier at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (above, as lead image) also depicts Olaf with his axe. The axe is understood as both his Viking war king attribute as well as his crusading symbol against Norse paganism.

Undredal Stave Church and Its Graffito: Olaf?

Medieval depictions of Olaf are sparse, so it is intriguing to look for extant representations, but his axe ought to be seen in any such renderings since it is his most important iconographic attribute. Thus, it may be important if Olaf appears in any 12th c. stave churches. One of the most altered stave churches and possibly the smallest is at Undredal in the Aurlandsfjord ca. 1147. At waist level on the south pine wood wall of the original nave, ostensibly original, restoration by removing later paint has revealed a carved or inscribed crude graffito – about hand-size in its dimensions – of a man holding a Viking-style axe. Of course, it does not have to be Olaf unless there is definitive evidence. Perhaps another corroborating line of evidence for the graffito axe-wielding man as Olaf is that there is also a dragon carving in the same Undredal wood wall not far from the axe-wielding man, and a dragon is also seen around Olaf depictions where his feet sometimes stand over a vanquished dragon, likely representing paganism as on the detail image of Nidaros Trondheim Cathedral facade above. Thus, while it remains to be proven that it is indeed St. Olaf holding the axe, this Undredal graffito depiction with such iconic features on the wall of one of Norway’s earliest churches is deservedly appropriate as a “holy” image of the saint king, which it may well represent.

Notes:

Oddr Snorrason. The Saga of Olaf Tryggvarsen. Cornell University Press, 2003.

David Farmer. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press, 2011, 5th ed., 272.

F. Metcalfe, ed. Passio et miracula beati Olaui. 12th century ms., Corpus Christi College Library, Oxford. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1881.