By Chelsea Glickman –

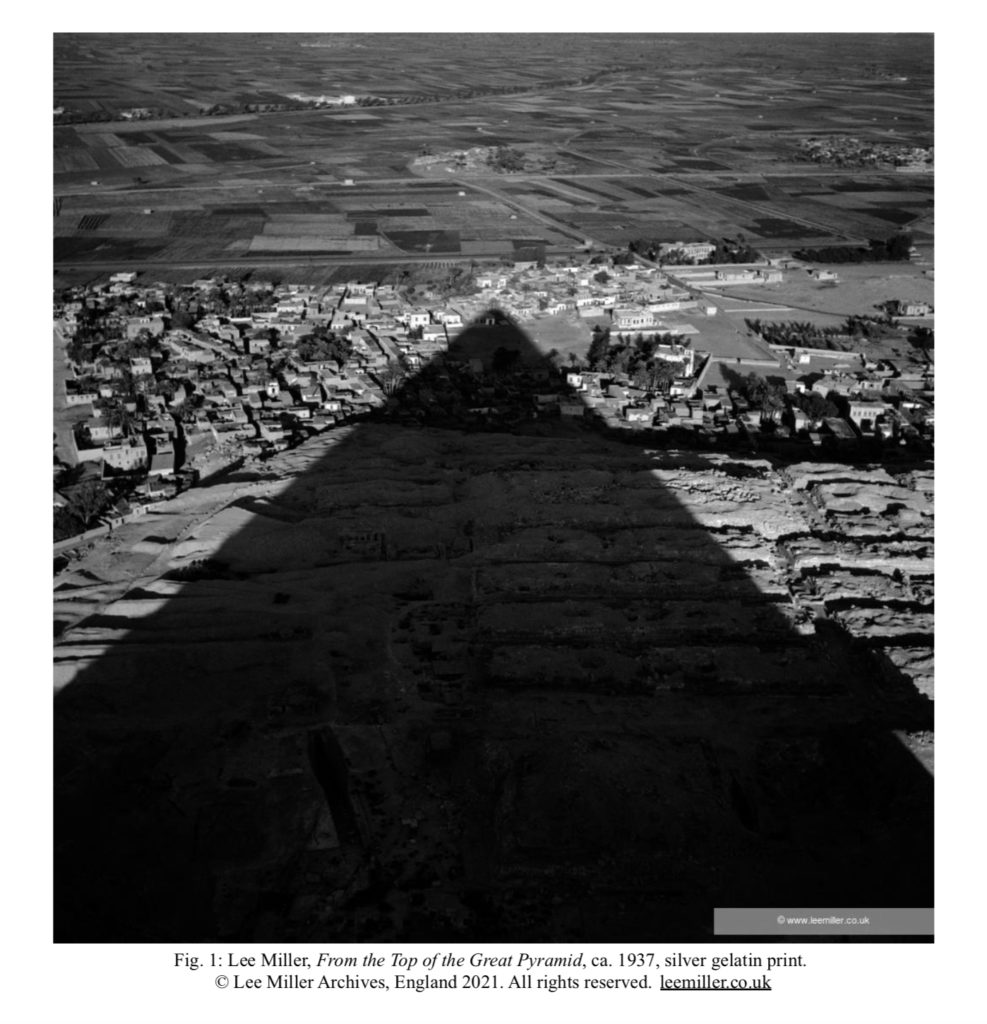

The rise of nationalism in Egypt is often associated with the political agenda espoused by President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the fifties and sixties, yet it may also be possible to view the politically-charged artistic practices that transpired in Cairo in the preceding decades as attempting to foretell the development of prominent nationalist ideals. Take for instance what might appear as a menacing triangular shadow that looms over a rugged landscape (Fig. 1). The object that casts this shadow is intentionally excluded from the photographic frame, but its iconic shape and massive scale indicate that it is none other than one of the Great Pyramids at Giza. Extending from the two corners at the bottom of the image, the shadow expands across three distinct registers, casting the darkest and widest shadow over the craggy limestone necropolis beneath it. As the pyramid begins to narrow into the distance, it penetrates a topographically demarcated residential area. It is here that the pyramid culminates into a point that directs the viewer’s eye to what lies beyond: a desolate landscape, illuminated and untouched by the monument’s shadow, that continues infinitely into the horizon. Without having to explicitly capture the pyramid itself, the artist behind the image has situated her viewer in an undeniably Egyptian landscape, appropriating its national symbology and rendering its absence in ways that might impose new meaning upon the site. This telling image was shot in 1937 by the American surrealist photographer Lee Miller. Primarily known for her apprenticeship with Man Ray and work as a photojournalist for British Vogue, Lee Miller’s From the Top of the Great Pyramid stands out in her oeuvre as bespeaking an exploration of landscape undertaken by Cairo-based surrealists in the thirties and forties in response to growing political and national tensions.

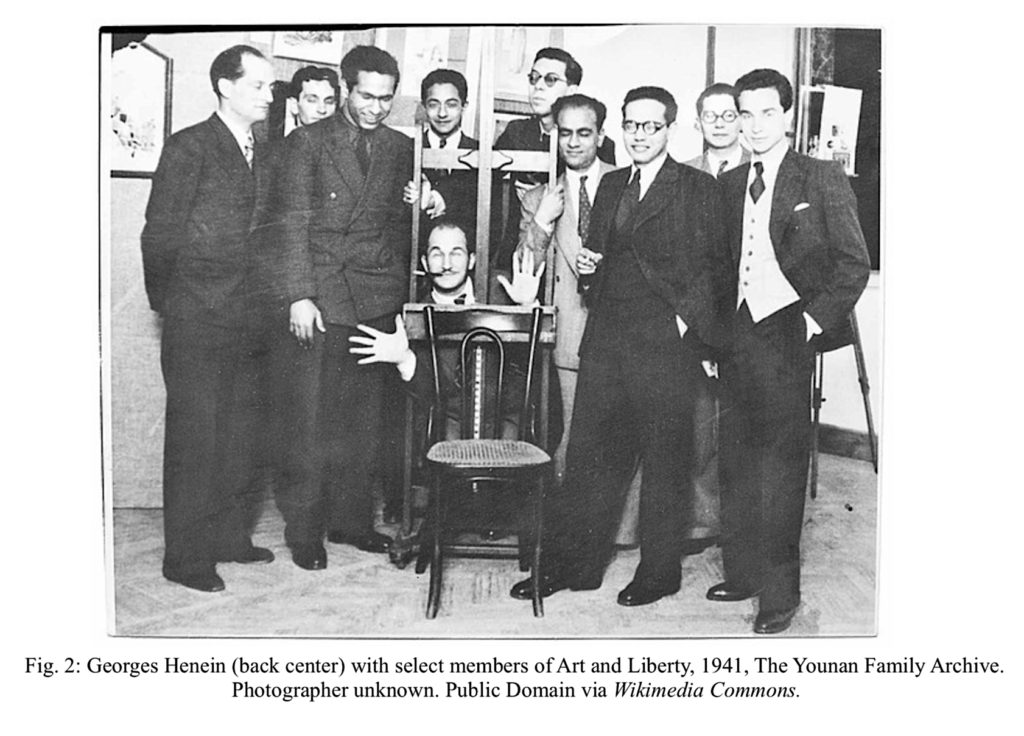

This relationship between landscape and national power is central to a thorough understanding of Miller’s From the Top of the Great Pyramid. Of particular interest is Miller’s engagement in a series of experimental and surrealist approaches to landscape produced and exhibited in Egypt under the auspices of Art and Liberty: a leftist group of artists and writers operating during the Second World War. While surrealist ideas had reached Egypt by a number of pathways, the poet Georges Henein was its primary conduit. In 1938, Henein established Art and Liberty as a faction of Fédération Internationale de l’art Révolutionnaire Indépendant (FIARI), which was initially spurred by the advent of André Breton and Leon Trotsky’s manifesto “For an Independent Revolutionary Art” that same year. Like Breton and Trotsky’s manifesto, the intellectuals who comprised Art and Liberty condemned fascism and political restrictions on artistic production. (Fig. 2) The group officially declared themselves with the signing and adoption of their own manifesto which sought to mock Hitler’s Entartete Kunst exhibition with its title “Long Live Degenerate Art”. (1)

Holding five exhibitions from 1940-1945, (2) Art and Liberty’s practice was not only stimulated by oppressive political regimes abroad, but the rise of growing nationalist sentiments and British imperial forces locally following the signing of the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty. (3) The group’s concern for emerging fascist sympathies led them to engage in artistic practices that aimed to dismantle conservative nationalism at home. For some, this involved creating surreal landscapes that challenged systems of national power. This was often accomplished by appropriating ancient monuments and forms that frequently infiltrate our vision of Egypt’s history and national image to assign them new meaning. It is thus possible to dub these landscapes “anti-national” in their intent.

Miller arrived in Cairo in 1934 (4) with established connections to Europe’s elite group of surrealists, ultimately providing Art and Liberty’s members international channels through which to disseminate their works globally. (5) Miller’s position as a kind of liaison who facilitated intellectual and artistic exchanges between Europe and Egypt’s most brilliant artists has commonly sat at the forefront of historiography tracking her years in Egypt. As influential as Miller’s networks proved to be, it is important to situate her work in conversation with Art and Liberty’s overall mission. Though her photograph From the Top of the Great Pyramid predates Art and Liberty’s establishment by just one year, her work clearly engages ideas of national and political tension. Like other members of Art and Liberty, Miller appropriated Egypt’s ancient monuments to challenge the nationalist ideals they tended to embody.

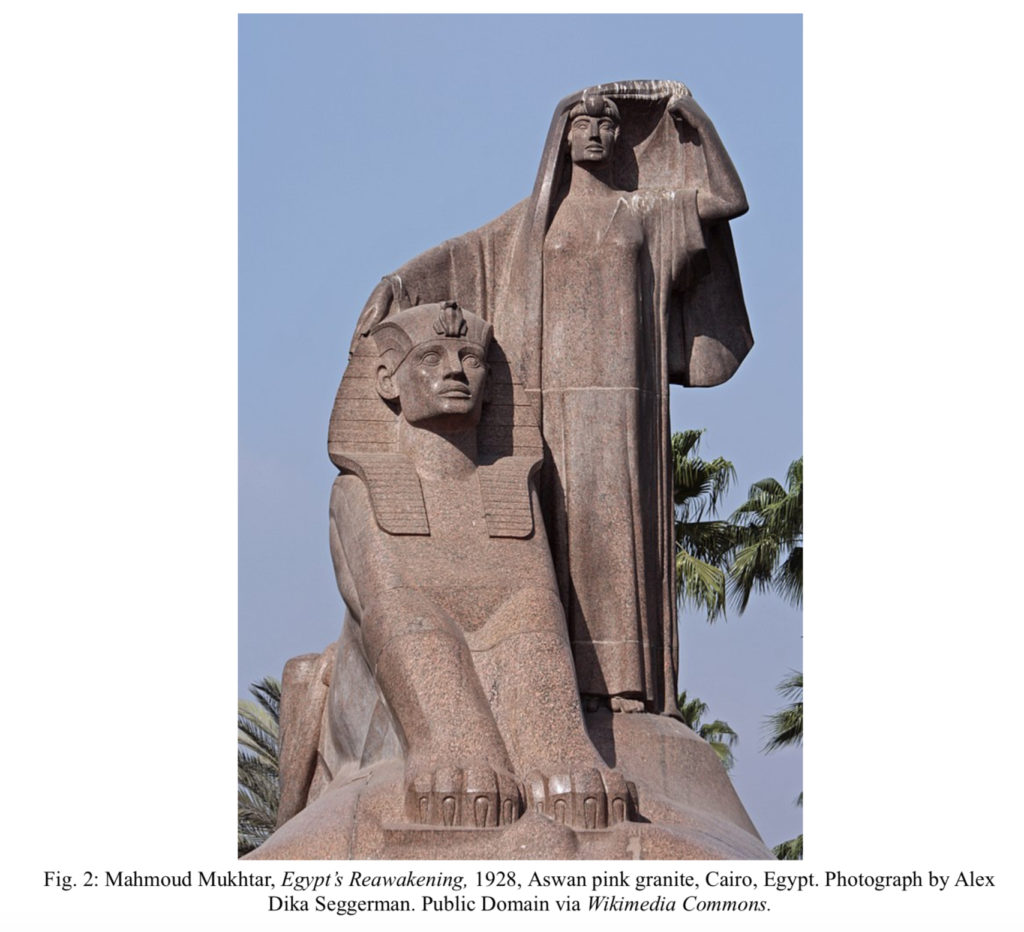

In fact, it may be possible to understand Miller’s photography as attempting to counteract more conservative works such as those produced by Egyptian sculptor Mahmoud Mukhtar [b. 1891- d. 1934] who, in the interwar years, developed a visual language that revived pharaonic imagery to represent the Egyptian nation. Mukhtar attended the Egyptian School of Fine Arts- a governmentally sanctioned art program established by Prince Youssef Kamal in 1908- and fused his training and interest in French neoclassicism with Egyptian symbology. Upon graduating art school, Mukhtar was equipped “to serve the nation” by sculpting national monuments. (6) His most famous work, Egypt’s Reawakening (ca. 1928), set the standard for a modern Egyptian art that promoted nationalist ideas (Fig. 2). The massive sculpture of a peasant woman unveiling herself as her right arm rests on the head of a sphinx celebrates the modern Egyptian nation while recalling its ancient pharaonic forms. The idea of Egyptian history is further evoked by Mukhtar’s cautious decision to sculpt with Aswan pink granite excavated from the local landscape as his ancient predecessors had once done. (7)

If we return to Miller’s 1937 photograph From the Top of the Great Pyramid, it’s apparent she related to ideas of the “national” quite differently than the heritage objects produced by Mahmoud Mukhtar in the preceding moment. Instead, Miller renders the Egyptian monument absent. By emphasizing the shadow cast onto the desert landscape, rather than the pyramid itself, Miller denies the monument its powerful presence and undermines its national significance. She seems to suggest that the national symbology embodied by the monument, and perhaps conservative politics more broadly, cast a looming and menacing shadow that consumes the Egyptian nation. This anti-nationalist sentiment is further evoked by the pyramid as it begins to narrow into the distance. Here, Miller draws her viewer’s eye to the illuminated desert beyond, evoking consideration for an alternate, or rather sur reality where triumphalist conservative and nationalist politics can no longer cast their shadow.

Sources

Bardaouil, Sam. “The Art and Liberty Group: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948).” In Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948), 18-32. Paris: Éditions Skira Paris, 2016.

Golia, Maria. Photography and Egypt. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2010.

Haworth-Booth, Mark. The Art of Lee Miller. London: V&A Publications, 2007.

LaCoss, Don. “Egyptian Surrealism and ‘Degenerate Art’ in 1939.” Arab Studies Journal 18, no.1 (Spring 2010): 80-84.

Seggerman, Alex Dika. “Mahmoud Mukhtar’s Pharaonic Classicism and Pedagogical Nationalism.” In Modernism on the Nile: Art in Egypt Between the Islamic and the Contemporary, 68-90. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Notes:

(1) Don LaCoss, “Egyptian Surrealism and ‘Degenerate Art’ in 1939,” Arab Studies Journal 18, no.1 (Spring 2010): 80-84.

(2) Sam Bardaouil, “The Art and Liberty Group: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948),” in Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948), (Paris: Éditions Skira Paris, 2016), 18.

(3) ibid., 28-32.

(4) Maria Golia, Photography and Egypt (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2010), 145.

(5) Mark Haworth-Booth, The Art of Lee Miller (London: V&A Publications, 2007), 132-133.

(6) Alex Dika Seggerman, “Mahmoud Mukhtar’s Pharaonic Classicism and Pedagogical Nationalism,” in Modernism on the Nile: Art in Egypt Between the Islamic and the Contemporary, (North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 68-72.

(7) ibid., 88-90.