By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Until recently, many of us were used to considerable mobility. Weekends away, summer holidays, conferences: all of those were part of our lives; we were modern and cosmopolitan.

When we think of the past, however, “mobility” is not really the keyword coming to our minds most readily. Without trains, planes or cars travelling was difficult and without such things as summer holidays there was little reason to go anywhere. Could we have been wrong?

Indeed, there were many reasons: Soldiers had to travel as long back as there were humans fighting wars against each other. The radius may have changed, the activity and need to travel did not. Much earlier, the Romans even built a network of excellent roads all over Europe and the Mediterranean – at least 50,000 miles – ostensibly to move troops around quickly and efficiently. Some people moved to new cities in the provinces and visited their relatives back home.

With the rise of court culture from the Medieval period onward, court artists started to follow the sovereign on progress to pick up commissions. Princes sometimes also lent their favourite artist to a peer. Artists occasionally followed their own work of art to a foreign country to assemble the parts or apply finishing touches.

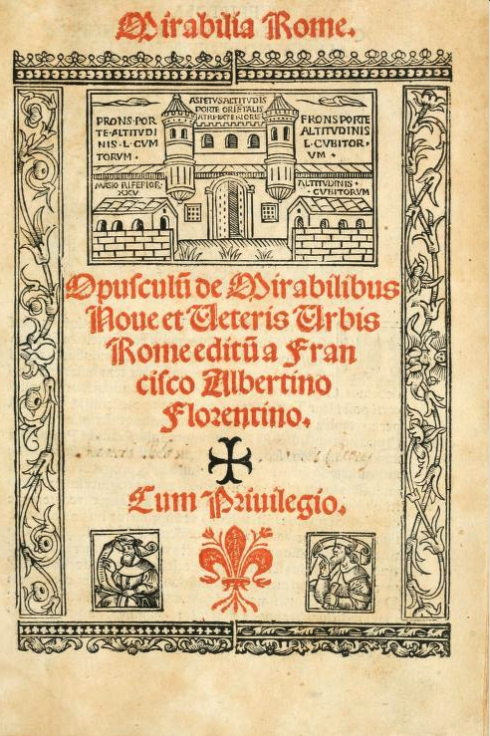

If we consider the above excellent reasons for going abroad, how about the fear of hellfire? Pilgrims had made up a large group within the travelling community since late antiquity. Rome, Constantinople and Jerusalem were major if far-away and difficult-to-reach destinations. Often the journey to a pilgrimage site was well organised with pilgrims’ hospitals and sight-seeing scheduled along the route. In fact, pilgrimages were not unlike cultural tourism and visited ancient monuments as well as the main churches. Guidebooks existed to provide the necessary information, for example the mediaeval mirabilia urbis Romae. Other cities followed the Roman example and, in 1510, Francesco Albertini composed a city guide to Florence. The early-modern guides often took the form of a short Memorial and combined descriptions of the main works of art with a general laudatio.

As Eliana Carrara and Monica Visoli show in their recent book on city guides from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, descriptions of cities, regions and particular sights were composed in early-modern Italy. The approach was not always one of a city guide trying to attract (foreign) tourists but one of pointing out the highlights (and importance) of the author’s hometown. Guide books eventually constituted a literary genre used for the debate between cities in their efforts for cultural supremacy.

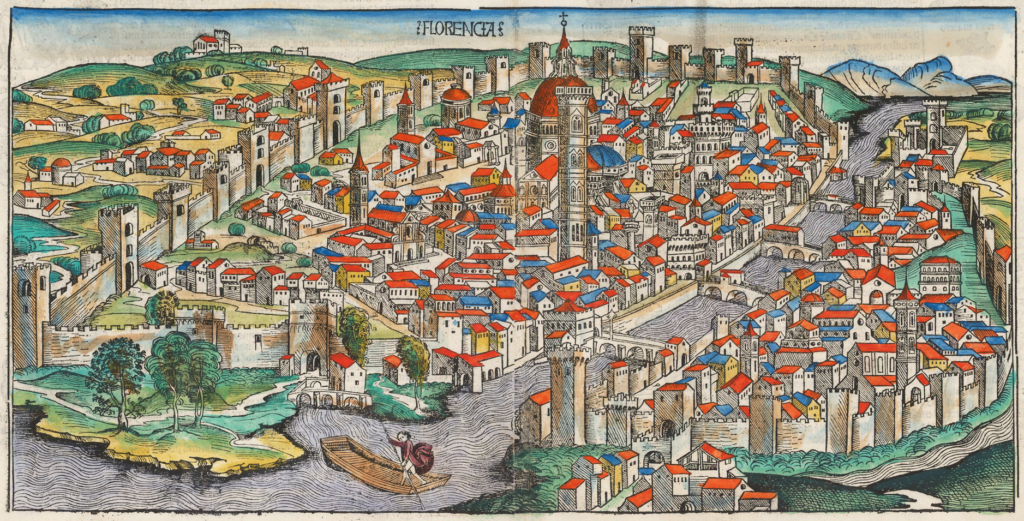

“Firenze città nobilissima” was advertised in a number of guide books composed by the above-mentioned Albertini, as well as by Francesco Bocchi and by his contemporary Paolo Mini. Although their works constitute three individual books, their aims were similar: they attempted to point out the beauty and nobility of their hometown. Bocchi gave a detailed account of famous buildings and works of art as part of touristic itineraries starting at the six city gates, he also discussed the reasons why these “beauties” needed to be admired and appreciated. Literary descriptions were matched by the visual presentations, for example by Stefano Buonsignori’s plan of 1584.

Obviously, Florence was not the only city to present its touristic highlights to potential visitors. It was part of a city’s identity to ensure that the outside world would understand its claims to nobility and fame. In the case of Bologna, Carlo Cesare Malvasia’s Le Pitture di Bologna (1686) remained the only guide book for over a century. Nonetheless, his work continued to be in use all the way to the advent of the Grand Tour and fulfilled Malvasia’ original offer of an inventory of Bologna’s cultural and artistic treasures. Venice projected its self-image as “teatro del mondo” and “città nobilissima et singolare” in Francesco Sansovino’s work of 1581. It was a privilege to write about Venetian art and history and permission was not easily granted. Sansovino however managed to publish Tutte le cose notabili e belle che sono in Venetia (1556), followed by his Venetia, città nobilissima, et singolare, Descritta in XIIII libri (1581). He was helped by the Venetian authorities who wished to create a strong image of their city. The chapters in Carrara and Visioli’s edited volume also include travel literature on Genoa, Milan and other Lombard cities or Pozzuoli.

It is clear that travel guides in Italy and other parts of Europe were not entirely what we would expect from a modern city guide, since they often mixed panegyric aspects with city politics but often left aside practical information for travellers. They were mostly concerned with examining their own (perceived) cultural importance and histories of their foundation myths. Nevertheless, much of the information included in these books could appeal to visitors by giving an account of the must-sees. If one looked for practical tips, for example on transport, accommodation or banking, pilgrims’ guides attempted to escort the courageous traveller through all kinds of pitfalls and dangers and still provided lists of “tourist destinations”.

City guides and city identities have the potential of being important and rather exciting topics of research. Certainly, they attest to a long-lasting history of mobility and an interest in travelling that may not be immediately apparent to us when we think of the past.

Eliana Carrara and Monica Visioli, eds. Le guide di città tra il XV e il XVIII secolo: arte letteratura, topografia(Seminari di Letteratura Artistica). Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, 2020. 255 pages, 64 figs. in b/w and colour. ISBN: 978-88-3613-034-4

Debra J. Birch. Pilgrimage to Rome in the Middle Ages. Continuity and Change. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1998.