By P. F. Sommerfefdt –

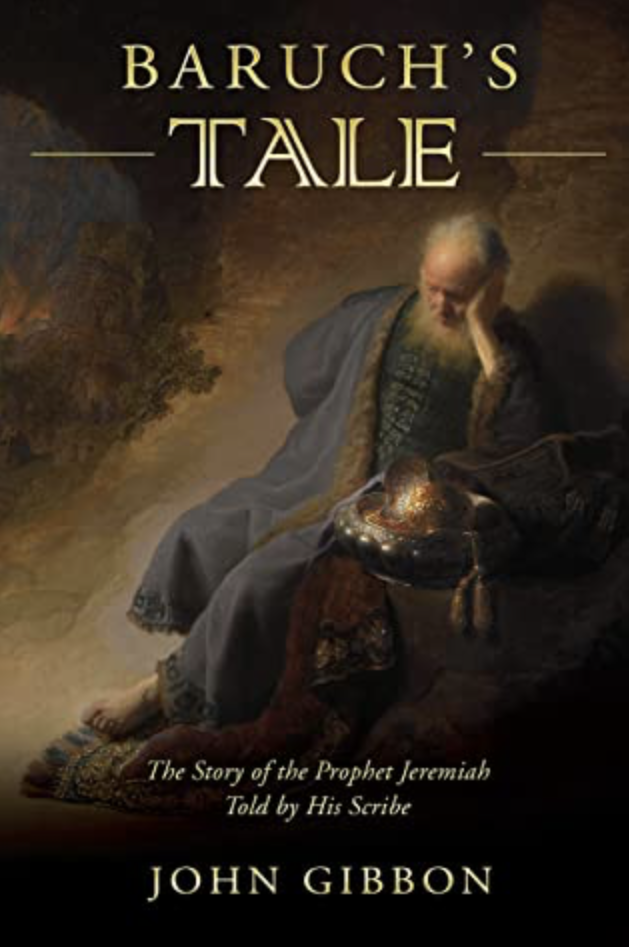

Rembrandt’s 1630 painting of the prophet Jeremiah weeping over Jerusalem is an apt image for condensing this historical novel to a singular time and place in history. Historical fiction often falls into one of two pitfalls or both – either too historical and dry in its detail or too fictional and errant on history. This novel (Baruch’s Tale, Stone Tower Press, 2020) about the role of Jeremiah’s scribe Baruch by John Gibbon is well-balanced between those contrasting requisites of fiction and history. After beginning in Babylon during the Exile, the pace gradually increases dramatically to a climax in the return to Jerusalem to rebuild and the challenges facing the Jews. It leads to a satisfying conclusion however daunting it must have been to have been born in Babylon and never having before seen the land of one’s forebears as was the case for most of the Jews as returnees after half a century or more in exile. If a Talmudic scholar had narrated these chapters as bonafide history, its commentary seemingly wouldn’t have been much different – a credit to Gibbon for assimilating so much Babylonian background and biblical exegesis. The Author’s Preface, Historical Time-Line and Glossary are also helpful front and back matters, although probably not necessary for those familiar with the historical context of the Neo-Babylonian Empire or the biblical prophetic texts.

While old Baruch is the main narrator along with Nebuzaradan – a high Babylonian military official now also in his old age – with many biblical quotations interspersed in their dialogues, the protagonist of the novel is the orphan Boaz, a bright young scribe in his teens who grows up and eventually learns military matters in Babylon for his return to Jerusalem under the reign of Cyrus, a coming-of-age bildungsroman passage that takes decades from 550 BCE to around 525 BCE. While Daniel doesn’t make a cameo appearance, his benign presence undergirds much of the narrative behind the scenes – he would surely be too old to return to Jerusalem across half of the Ancient Near East and its vast plains.

One of my favorite passages is right at the beginning where young orphan Boaz warily treads the dense streets of Babylon with its range of humanity from downtrodden slaves to proud nobles and its almost overwhelming sights, sounds and smells from the Euphrates to its towering temples and rich markets. Another favorite passage is near the end when a much older Boaz solemnly surveys the weedy ruins of Jerusalem – experiencing both elation at finally being in his unknown parents’ homeland and a somewhat heavy heart for what tragedies of human error had transpired.

John Gibbon has really done his homework for this tale, so his factual accuracy is without much quibble and his quotations from Jeremiah and other prophetic books are always relevant to the development of the story. But his descriptive writing is also vivid without being overly colorful. Babylon comes alive in all its teeming cityscapes, idolatry, slavery, conquests and checkered past, especially in the sensory language Gibbon employs in his descriptions.

By the end of the novel, one easily comes to respect Boaz whose life turned out so different from his own scribal expectations. Nearly every character in the book can be found in the biblical texts – even if for only a brief mention or two – and this ekphrastic novel will remain in one’s memory for a long time. I’ll likely never be able to read the prophetic books of Jeremiah or Lamentations again without this well-crafted book’s rich imagery pictured in my mind.