By Patrick Hunt –

High above Palermo near Monte Caputo is one of Christendom’s jewels: Monreale Cathedral. It has been called the “Golden Temple” for centuries, at least since the poet Bartoldo Sirilli published these lines in 1596:

“Like a crown on the distant mount on marble base a golden temple lies…”

As a wonderfully hybrid work of eclectic art, Monreale has a Norman context with Latin architecture, Byzantine Greek internal decoration, and Islamic exterior decoration. Yet Monreale is now mostly unprepossessing in its reworked exterior viewed from the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele.

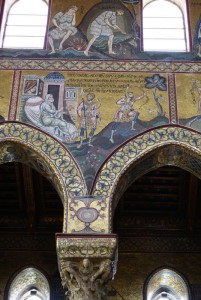

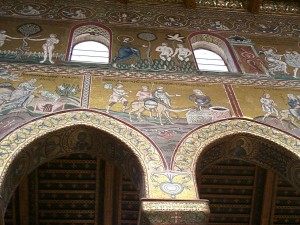

Where it hasn’t been reworked later, its strongest Arabian influence is now mostly seen in its exterior decorated triple apse, itself filled with intricate geometric traceries of black volcanic stone and beige limestone intarsia. Some call this hybrid style “Arab-Norman” and others “Sicilian Norman.” But it is the interior that dazzles most with its many thousands of gold tesserae narrating the stories of the Bible.

If visitors to Palermo only see the jewel of the Palatine Chapel in the Norman Palace, they do catch a concentrated vision of mosaic glory, but when compared to the open basilica grandeur of the much vaster space of Monreale, the cathedral is all the more inspiring in both much greater size covered in a high volume of glass mosaics (6500 square meters) as well as the scope of the illustrated biblical texts depicted.

William II, “The Good” King of Sicily, (1155-89) conceived of a magnificent church that would eclipse the earlier coastal royal church at Cefalù built by his grandfather Roger II (1095-1154), and also enhance his own personal majesty. The bulk of Monreale was constructed from around 1173-76 shortly after the beginning of William’s reign and it was dedicated in 1182 when finished. Built adjacent to the earlier royal hunting lodge transformed into a palace, from the terrace east of the exterior apse one can still see the curved coastline far below, the Concha d’Oro (“Golden Shell”) where the distant city meets the blue sea. The valley between the mountains and the sea was once filled with fragrant royal citrus groves.

Monreale Cathedral’s size is 102 meters in length from narthex portico to nave to apse and its width around 40 meters; its adjacent cloister is 2200 square meters in size. The cloister is one of the most beautiful in the Romanesque world with its Islamic influence in the intarsia of decorated arches of the arcade and its over 200 Byzantine mosaic tesserated double columns (plus four at each corner), each one with a unique Romanesque capital – most of these also relate additional narratives from biblical or other lore.

The Arabesque fountain (literally designed by Islamic artists) in the southwest corner of the cloister is one of the treasures of the Benedictine cloister completed around 1200. When spraying from many arcing “water branches” it deliberately resembles a palm tree. Its water power employed the siphon, where water from adjacent hill springs coming at volume and pressure from higher elevation causes the fountain water to spray upward naturally.

The original cathedral floor has been replaced in the Renaissance except for the sanctuary and apse, which retain the 12th c. Cosmati style of Roman colored stone guilloche (“double rope”) patterns, also called opus alexandrinum (“Alexandrian work”). There is still debate if the internal granite columns (one is actually green cipollino) are from Classical ruins around Palermo or more contemporary. Baroque modifications to the cathedral were undertaken in the 17th century by Cardinal Alfonso Los Cameros.

The main portal bronze double doors from the narthex are a masterpiece from 1186 by the master Bonanno Pisano of the famous family of metalworkers. The 40 bronze panels also tell the biblical narrative from Creation to the Ascension of Christ, starting form the bottom just above the lion and griffin-decorated base panels. The lowest dado element of the aisle walls have Islamic patterns of design in intarsia of colored marbles.

Inside the nave, the panoply of dual upper mosaics starts with Genesis texts of Creation and ends with Jacob’s wrestling the Angel in two zones, the Creation, Fall and Banishment and Gods command to Noah in the upper zone of the clerestory and the following vignettes starting with Noah building the ark below and continuing with the Abraham, Isaac and Jacob narratives in the arcade spandrels. Therefore the nave mosaics are entirely from the book of Genesis.The New Testament internal aisle mosaics start with the Nativity continue with Christ’s life and miracles and end with his last week in Jerusalem.

The huge image in the central apse is Christ the Pantocrator, “All Powerful Ruler”. The overall visual iconography is Eastern but with Latin summaries in the vignettes. In the sanctuary and apse the mosaics are of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection and lives of major saints like Peter and Paul. A total of 130 different biblical scenes are portrayed in the Byzantine mosaic style, following the calendrical scripted lessons of the Greek Menologion or monthly cycle that the astonishing array of mosaic images amplifies.

It is the upper nave of the Old Testament scenes and the aisle wall of New Testament scenes that have caused many pilgrims to admire Monreale’s peerless mosaic art in gold background. One of the most poignant mosaic scenes is Adam and Eve toiling after banishment from Eden. Clothed in shaggy sheepskin, a pensive Eve wearily and sadly sits holding her spool of wool and spinning tools, while a morose Adam with head downward is bent over the soil with an adze tilling the ground and chopping at its brambles. The succinct Latin text condenses and abbreviates the Vulgate of Genesis 3 and 4 with his curse: AD ASTRÆ PER ASPERA, “Adam begins to work…” These mosaics are huge as larger than life visualizations of biblical tales, and with much emotional expression in their faces become immensely personal rather than otherworldly and remote.

The Viceroy Giovanni de la Muta in 1498 speaking for King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Sicily stated:

“His Majesty is of the opinion that the church of…Monreale is one of most magnificent works of art to be found anywhere in the world.” [1]

Others who have marveled at or appreciated Monreale include Goethe, among many other keen admirers of historic great taste. More than the religious mosaic narratives, Goethe praised the high view as well as the fountains en route (possibly also including the unique cloister fountain):

“Today we drove up the hill to Monreale on an excellent road built by an abbot of the monastery at the time of its enormous wealth…trees here and there and more conspicuously, both high-spouting and running fountains, decorated with scroll ornaments of an almost Pallagonian eccentricity, but refreshing nevertheless to beasts and men…passing Monreale and reaching the top of the ridge we saw a beautiful landscape that spoke more of history than agriculture.” [2]

Goethe also said, “Sicily is the key to Italy” and that the cape of Monte Pellegrino near Palermo was “the most beautiful promontory in the world”. He chided anyone traveling to Italy without seeing Sicily, universally agreed to be the crossroads of European history. Most modern visitors who spend a few hours at Monreale awed by the seemingly endless mosaics and the symmetry of the cloister and the splendid vistas loved by King William II fully agree.

Notes:

[1] Quoted in Giuseppe Schiro. The Cathedral of Monreale: City of the Golden Temple. Palermo: Editrice Mistretta, 2002, 10

[2] J. W. von Goethe. Italian Journey (1786-88). W. H. Auden and E. Mayer, trs. London: Penguin, 1970, 242 and 259. Goethe’s visit was in April, 1787.