By Patrick Hunt

Why are the crisp Alto Adige wines not more well-known? In June I spent a week around Bolzano (Bozen in German), tasting and drinking great local wine. In the Alto Adige under the Alps, Bolzano is that wonderful combination of the best of both Italy and Austria. Annexed to Italy in 1919 from Austria, German culture and language hybridize with Italian language and amore per la vita under these lovely mountain valleys with vines growing up the slopes to great heights. Above Bolzano, the ‘Rosengarten’ Dolomites bask in alpenglow to the east.

Surprisingly to some, wine history here goes back to Roman times and before, at least to 500 BC. Several museums have Roman artifacts including the Museo Archaeologico dell’Alto Adige (Südtiroler Archäologiemuseum) – also home of Ötzi the Iceman, the 5,300 year old ice mummy – and the Südtirol Museum of Wine in Kaltern. Wine ladles and pruning hooks are some of the artifacts in the collections and locals insist the Rhaetian tribal viticulture was using wooden barrels about 15 BC when the Romans built roads that connect here, like the Via Claudia Augusta over the Pons Drusi (Bridge of Drusus) over the Adige River. Since Romans like Pliny, Virgil and Martial all praised Rhaetian wine, there’s a possibility they could have even intended wine of Alto Adige. Medieval viticulture was underway with both Italian passion and Austrian precision. Later during Habsburg rule, imperial authority greatly supported quality winemaking in the Alto Adige, which enjoys about 300 days of sunshine per year and cultivates over 20 different grape varieties. Some of the highest summer heat in Italy is in the Bolzano valley – I repeatedly saw 35 ° C in late June – which is perfect for ripening grapes. Locals joke that there are 40 vines per every Bolzano resident and that if “Venice floats on water, Bolzano floats on wine.”

I can well believe these statements once I saw vines growing everywhere imaginable along the river valleys and climbing the ridges from above Trento through Merano and the Adige Valley. According to the wine Alto Adige wine industry and wine lovers who’ve spent any time here, its quality wines are distinguished in a tiny wine region that stretches less than 50 miles south to north:

“Around five thousand winegrowers tend just 5,300 hectares (13,100 acres) of grape-growing areas in different climatic zones with variable types of soils and at elevations ranging from 200 to 1,000 m. (600 to 3,300 ft.) above sea level – a wide variety that brings forth a considerable dense concentration of top wines. This is confirmed by a quick look at the leading Italian wine guide: for years now, Gambero Rosso has awarded Alto Adige the largest number of top scores (“Three Glasses”) in proportion to its total vineyard area.” [1]

This is in contrast to Tuscany and Piemonte wines, grown in much larger total areas of wine region but with less overall distinction, since more wines (98%) have Italian DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) protection appellation here [2] than anywhere else in Italy with diverse microclimates and a complex geology ranging from the eroded limestone soils of the Italian Prealps around Trento to the Venosta sands and Merano shales, mica schists and phyllites to the porphyry soils of the Dolomites around Bolzano. Yet less than 5% of these wines are even exported to the U.S., much (49%) being consumed regionally. Many of the wines are grown on pergolas and high Guyot trellises, whose X-cross beams can be seen all over the valleys almost from east of Lago Garda northward.

Although Alto Adige white wines are far more famous – Pinot Grigio (also known here as Grauer Burgunder or Ruländer), Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc, indigenous Gewürztraminer along with Müller Thurgau, Sylvaner, Riesling, Veltliner, Moscato Giallo (Goldmuskateller) and Kerner – making up 55% total volume in the Alto Adige, its red wines (45% total volume) include the indigenous Schiava and Lagrein as well as Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Moscato Rosa, among others. Schiava is also known as Vernatsch in German as well as Trollinger (from Tirol) elsewhere in Germany. A light cherry red wine, Schiava is blended with the fuller bodied Lagrein for breadth and depth. More Schiava (22-30%) grapes are grown here than any other grape varietal, with Pinot Grigio a distant second (11%). Many consumers prefer the light Schiava – “berry and almond aromas” – blended rather than by itself. Schiava is also known in Germany as the Black Hamburg grape. Some of the Alto Adige wines can also be designated by the Germanic QbA rather than Italian DOC designations. [3]

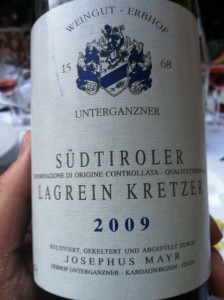

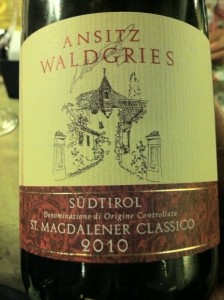

One of my new Bolzano favorites here is a cuvée blending several varietals: the Sankt Magdalener (Santa Maddalena) of the village of the same name just east of Bolzano in the hills. Sankt Magdalener unites Schiava and Lagrein in a cuvée percentage depending on the vintner but often around 80% Schaive and 20% Lagrein. [4] I tasted multiple wines, including those of Josephus Mayr, a family making wine since 1568, as well as other red wine blends such as the velvety Lagrein Kretzer Weingut – Erbhof of Josephus Mayr (2009), the memorable Ansitz Waldgries St. Magdalener Classico (2010) and the Hans Rottensteiner St. Magdalener (2010). In his iconic Sotheby’s Guide to Classic Wines, Molyneux-Berry also highlighted a quality Sankt Magdalener (Oberingram Sankt Magdalener) from Alois Lageder, [5] which was my introduction to this wine. These blended Sankt Magdalener red wines are worth drinking alone for vivid flavor or paired with the Bolzano cuisine with its distinct Austrian touches of juniper flavored speck (ham) on schüttelbrot, wurst with schwartze trüffel and spinach knödel dumplings. Of course, you can just as easily have tagliatelle con porcini because it is still also Northern Italy.

If possible Roman esteem is not enough, Alto Adige wine has been rightly praised by medieval Tyrolean poets like Oswald von Wolkenstein (1377-1445) and even highlighted in a fresco on a wall in Brixen (Bressanone) cathedral. In Bolzano and other towns, decorated with old Gothic script on buildings and wrought iron signs hanging from old shops, you would hardly know you were in northern Italy. Other than a few even older Italian Romanesque campaniles here and there, most of the church towers have Baroque German bronze onion-dome bell towers. After enjoying the sunshine of Bolzano in the vineyards under distant snowy peaks, I totally agree with the poet Heinrich Heine about the Südtirol here:

“In southern Tyrol, the weather cleared up, the sun from Italy allowed its nearness to be felt, the mountains grew warmer and shinier, I began to see entwined around them wine grapes, and I could begin to lean out of the coach more often.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Vini Alto Adige/ Südtirol Wein, Consortium Alto Adige Wines, Via Crispi 15 I-39100 Bolzano/Bozen; EOS – Export Organization Alto Adige of the Chamber of Commerce of Bolzano/Bozen, 2011, 5.

[2] “virtually the entire production” (4,940 hectares out of 5,000 ) according to Daniel Thomases in Jancis Robinson, ed., Oxford Companion to Wine, Oxford, 1994, 26.

[3] David Molyneux-Berry. Sotheby’s Guide to Classic Wines, New York: Ballantine Books, 1990, 226

[4] D. Thomases, up to 15% Lagrein in 1994, 849.

[5] Molyneux-Berry, 226.

[6] Heinrich Heine. Travel Pictures III, Chapter XIII (1830)