By Andrea M. Gáldy –

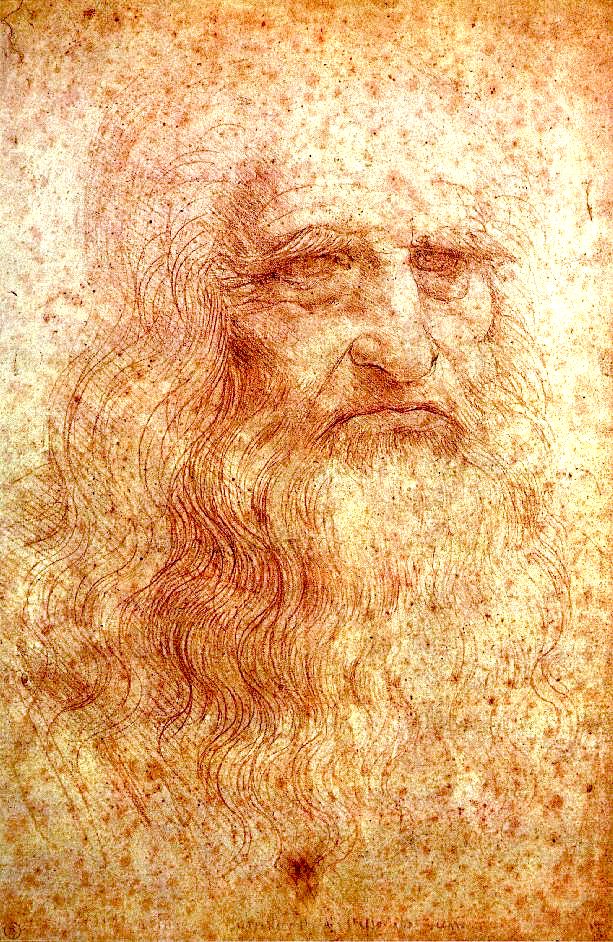

Leonardo is dead, but he has never been as popular as now. Almost exactly 500 years ago, he died in France. By then, Leonardo had long left his native Vinci, had been apprenticed to Verrocchio in Florence and had spent time working in Rome, Milan and Venice as well as in the itinerant retinue of Cesare Borgia. In 1515, Leonardo met the French King Francis I in Bologna and, from 1516 until his death on 2 May 1519, remained under his patronage in France. Today, Leonardo together with his contemporaries Michelangelo and Raphael is regarded as one of the great genii of the High Renaissance. He caused amazement and scandal while his was alive and his works, for example the Mona Lisa (c.1503), belong to the most admired and visited paintings in the world. The Salvator Mundi (c.1500) was sold at auction for a shocking $450.3 million in 2017 and the mystery of its present whereabouts adds to the allure. Leonardo’s appeal is such that he has long entered popular culture through novels (Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code, 2003), video games (Assassin’s Creed II, Leonardo da Vinci) and, most recently, a music video filmed at the Louvre (Beyoncé and Jay-Z, Apes**t, 2019). Everyone knows of Leonardo and his name alone is guaranteed to make visitor numbers surge at museums and exhibitions worldwide. The Louvre hosts a blockbuster exhibition on Leonardo (24 October 2019–24 February 2020), already marketed as “the one show you should visit in Paris this autumn” with fourteen paintings, supposedly comprising the Salvator Mundi. And, unsurprisingly, prospective visitors will have to book in advance, since numbers had to be limited.

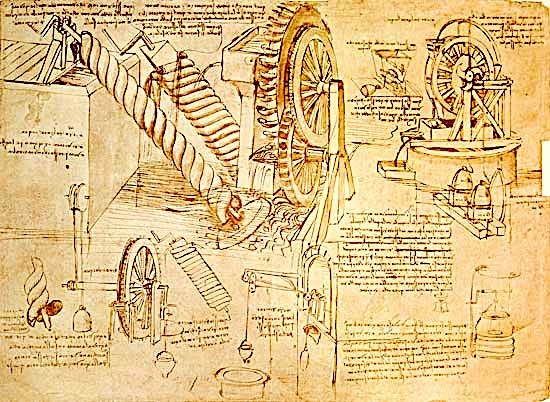

Celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death this spring in Italy include the reopening of the Museo Ideale di Leonardo da Vinci at Vinci with a display of unpublished documents and of what might be the artist’s hair and ring. Meanwhile in Florence, a major new exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello looks at Leonardo’s master Verrocchio (9 March to 14 July 2019; to move later in the year to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 15 September 2019 to 12 January 2020). At the Sala dei Gigli, Palazzo Vecchio, an exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci in Florence. Selected Folios from the Codex Atlanticus” can be enjoyed until 24 June, ideally in conjunction with “Leonardo and His Books. The Universal Genius’s Library” displayed at the Museo Galileo (6 June to 22 September 2019) and complemented by “Botany and Leonardo: Synthesis between Art and Nature” at the former dormitory of Santa Maria Novella (13 September to 15 December 2019). The above selection of events shows that, while Leonardo is being remembered this year at museums and institutions, apart from Paris the focus is not necessarily on his most well-known paintings. Rather, the emphasis lies on his collaboration with other artists, on his drawings, his c.200 books, on his many inventions and on his studies and experiments (see for example the anatomical drawings included in the current exhibition “The Renaissance Nude” at the Royal Academy, London, until 2 June). Leonardo is often celebrated as someone whose boundless spirit of experimentation is often considered as radically modern and as a person that would not be held back by the rules of his time. In actual fact, despite the disadvantage of an illegitimate birth and little schooling in childhood, he became the well-read owner of a considerable library. His intellectual curiosity led him to experiment with new technologies and materials; he was a keen observer of natural phenomena and a careful student of human proportions and anatomy. Although able to transform this knowledge into fine art (St Jerome in the Wilderness, c.1480, Vatican Museums), he was occasionally hampered by experimental techniques that led to the premature deterioration of some of his oeuvre, for example the Last Supper (1505, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan).

In keeping with the general emphasis of innovation and invention, in Germany this spring Leonardo’s interest in and engagement with engineering is in the focus of yet another exhibition (3 May to 1 December 2019) held at the museum of the University of Tübingen (MUT): EX MACHINA – Leonardo da Vinci’s Machines between Science and Art. On this occasion, the university museum displays 50 objects built after designs by Leonardo at Schloss Hohentübingen. Although there is no direct connection between Leonardo and the city or university of Tübingen, there exists a bond via the interdisciplinary study of fine arts, sciences and nature as undertaken by Leonardo more than 500 years ago and ideally continued by universities to this day. The University of Tübingen exceptionally maintains an institution dedicated to the organisation and display of 70 departmental collections, including works of art, archaeological objects and ethnological artefacts, some of these brought back from James Cook’s expedition to the South Seas, and makes them available to research and teaching.

The current exhibition (with cards and posters in English and German) as well as the catalogue (only available in German) combine therefore several genres into a display that presents Leonardo’s artistic creations as the framework and starting point of his scientific studies, e.g. anatomical investigations, and of his engineering projects. While trained as an artist in Verrocchio’s workshop, he educated himself in the mechanical arts on the basis of observation and experiments. His drawings, in particular, document his way of thinking and his methodology of translating his perceptions onto the page in front of him. Thus the exhibition presents itself as one large workshop, in which 50 astonishing machines demonstrate the results of work in progress from observation to invention. These technical models and replica are based on Leonardo’s designs and were manufactured by Italian artisans by means and with materials used in early modern Europe. Therefore, the main exhibits range from testimonials of cultural history to products of experimental archaeology. They are displayed in a context of curatorial installations that seek to illustrate the current Leonardo myth, the master’s engineering inventions, his mechanical achievements, military innovations and his designs and studies.

The exhibition is displayed within a dramatic choreography of darkness and light which gives every piece its due. The objects are surrounded by diverse genres of collectables from the permanent collection to provide an additional artistic and scholarly context similar to what the individual contributions in the catalogue attempt to do. The show is complemented by a particularly varied outreach and pedagogical programme for children as well as by lectures and workshops and is therefore to be recommended to a very diverse audience able to appreciate the wide range of topics presented and discussed.

Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Museum der Universität MUT, “Ex Machina: Leonardo da Vincis Maschinen zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst”, 3 May to 1 December 2019: https://www.unimuseum.uni-tuebingen.de/en/exhibitions/special-exhibitions/ex-machina.html