By Patrick Hunt

Jean A. D. Ingres (1780-1867) painted Dante’s story of Paolo and Francesca as an ekphrasis in similar settings multiple times, beginning in 1819 and through at least to 1856. (1) This article summarizes Ingres’ Paolo and Francesca (48 cm x 39 cm), 1819, Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts. According to the Louvre, Ingres was fond of a “troubadour style” and returned to this theme of “troubled or thwarted passion” on multiple occasions. (2) As literary antecedent, Eleanor of Aquitaine had introduced the new troubadour style in her “Courtly Love” with its trouvères to France, (3) openly promoting lyrical love poems by Chrétien de Troyes as well as by the likes of Wolfram von Eschenbach. Such narratives, where men kneel low before their ladies, often cite thinly-disguised seductive or adulterous love as seen in this famous scene of Ingres and in the narrative of the even more famous Dante canto.

Our primary historic source for the tragic story is Dante himself. (4) Francesca da Rimini’s father Guido da Polenta, Duke of Ravenna, had secured peace with his Malatesta enemy neighbor, Malatesta da Verucchio, the lord of Rimini, and cemented it by negotiating marriage of his daughter Francesca with the son Giovanni Malatesta (Gianciotto), a likely cripple. The Malatesta heir Gianciotto substituted his handsome younger brother Paolo as a deceptive proxy for the wedding and there the incendiary relationship smouldered and soon combusted. According to legend, Gianciotto slew his brother Paolo and Francesca having found them together, the moment Ingres narrates with the kiss.

In Inferno Canto 5:82-7, Dante meets the damned lovers in the second circle of those who sinned against the flesh, shades “carried on the assailing wind”, alluding to Virgil, his poetic guide in more ways than one:

Even as doves when summoned by desire

borne forward by their will, move through the air

with wings uplifted, still, to their sweet nest,

those spirits left the ranks where Dido suffers

approaching us through the malignant air,

so powerful had been my loving cry. (5)

Dante well knew that his dove simile would remind readers familiar with Aeneid 6:190 ff that Virgil long before had prior used doves to represent his mother Venus as the goddess of love in order to find the entrance to the Underworld at the Avernus, (6) also infamous for its malignant, sulfurous air from volcanic activity in the caldera of the Campi Phlegraei (“Burning Fields”).(7) Roman familiarity with the Campi Phlegraei was certainly a given judging by votives and shrines there. (8) If this literary association of Dante and Virgil is accidental, it is still a commonplace that doves were emblematic of steadfast human love – doves purportedly mate for life – and thus a fitting love symbol for both Virgil and Dante as his visible successor. Dante, however, inverts an underworld quest blessed by Venus (Aeneid Book 6) to an ephemeral tryst cursed by society and God into an eternal underworld embrace (Inferno Canto 5). This stolen kiss is not so steadfast as interminable.

Somehow echoing the Archaic Greek Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite where the often capricious goddess of love has power over all living creatures and where passion can explode gentle dreams into genocidal disaster, Dante makes these words Francesca’s:

Love, that releases no beloved from loving,

took hold of me so strongly through his beauty

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.

Love led the two of us unto one death.

Caïna waits for him who took our life.

These words were borne across from them to us. (9)

Dante has parodied I Corinthians 13 where agape trumps eros in the end. But not here. In her desire for vengeance over violence, “because of the fair body taken from me – how that was done still wounds me”, Francesca implies Gianciotto Malatesta is the one for whom Caïna waits. In Circle 9 of the Inferno, Caïna is almost at the very bottom of Hell where the worst of the treacherous are punished, named after biblical Cain who murdered his brother Abel because God preferred Abel’s sacrifice. (10)

In this painting of Ingres, Paolo and Francesca have just finished reading love poetry about Launcelot’s kiss to Guinevere when the two succumb not to perfume, body proximity and privacy – all that would have been too easy – but to a subtler literary beguilement, a “Gallehaut” as Francesca curses in Dante’s tale:

One day, to pass the time away, we read

of Lancelot – how love had overcome him.

We were alone, and we suspected nothing.

And time and time again that reading led

our eyes to meet, and made our faces pale,

and yet one point alone defeated us.

When we had read how the desired smile

was kissed by one who was so true a lover,

this one, who never shall be parted from me,

while all his body trembled, kissed my mouth.

A Gallehault indeed, that book and he

who wrote it, too; that day we read no more. (11)

Gallehaut was Lord of the Distant Isles in Arthurian lore and in the 13th c. French Lancelot epic. He acted as a panderer for Dante because he was the legendary go-between for the adulterous Lancelot and Guinevere. Francesca may be dissembling, however, in blaming her fate on an inanimate book rather than on her own will. History sometimes suggests that both Paolo and Francesca had children independent of each other before they met and were therefore less innocent of the flesh. Dante’s version, however, fits better with Courtly Loving and Francesca’s pitiable rationalization as well as providing the stimulus for Ingres’ painting, even if we don’t quite fully believe Francesca that books are that dangerous, completely blinkering our power of reason and suspending all capacity of judgment when experience is vicarious as here.

Dante cites the physiology of desire in some of lust’s overwhelming symptoms: locked eyes, pale faces (because their blood is likely rushing downward to their gonads), trembling, and finally kissing. Pale faces may also be proleptic for their impending death. Yet the implausible agency is not their willing flesh but a book. Ingres has Francesca dropping the fatefully heavy book, swooning and unable to control her body gone limp as Paolo – the aggressor in Francesca’s mind – swoops in for a supple kiss, also gently touching her neck and hand with his roaming hands.

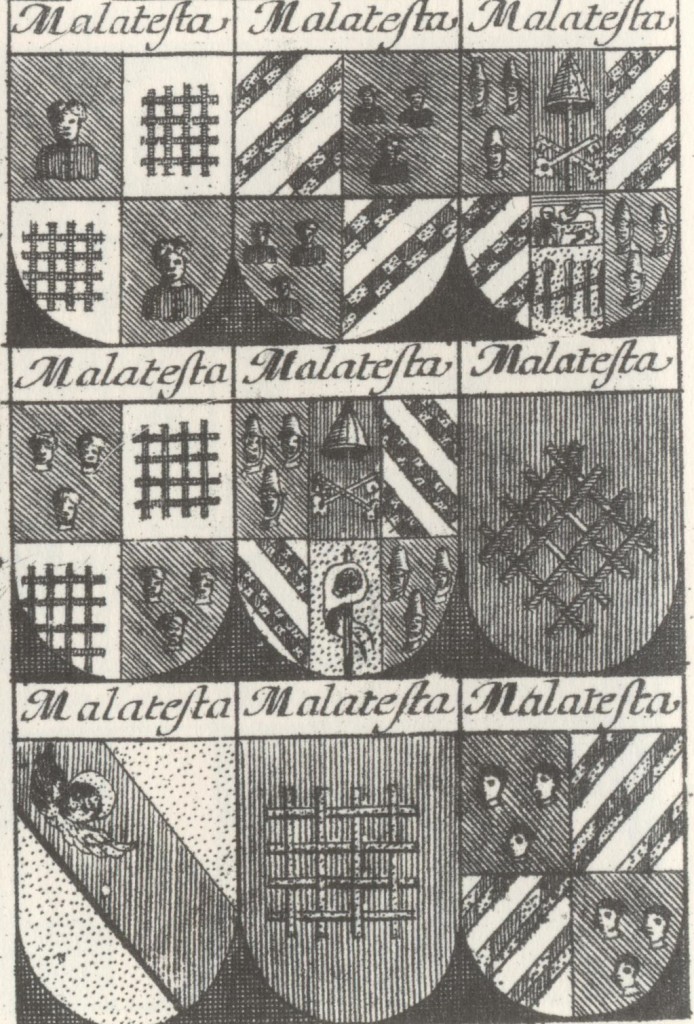

Pulled aside by the furtive Gianciotto who enters quietly behind the curtain in the right rear drawing his murderous sword, this red curtain protecting their privacy also contains the decipherable heraldry of both Rimini and Ravenna houses, with the more recognizable Malatesta scudo on the left above Francesca and her own simpler, single bar dexter on the right.

Dante’s character swoons as well in this vicarious contagion of love, maybe because he reminds his Inferno too is a literary construct. Could Dante also be referencing the lust-driven sinners of Jude 1:12b-13:

They are clouds without rain, blown along by the wind; autumn trees, without fruit and uprooted’twice dead. They are wild waves of the sea, foaming up their shame; wandering stars, for whom blackest darkness has been reserved forever.

One of Francesca’s narrative starting points was that “One day, to pass the time away…” Now time has indeed passed away into eternity. The old debate about how much Paolo and Francesca suffer swirling about in the Inferno – they are together after all, as many have pointed out, somehow suggesting Amor omnia vincit even in Hell and that love damned is yet a faint Imago Dei – misses most of the point of contrapasso: Paolo and Francesca are stuck together forever, never able to part even if they wanted to. They have lost all of their volition, of self-generated movement, of individuality, and are at the whim of the maelstrom just as they were unable to resist the fractional physical whim of a single kiss. Is this choice or consequence? Dante’s character may pity them but Dante the poet does not mitigate their hell. This inextricable, now forced union between Paolo and Francesca could even be the existential starting point of Sartre’s No Exit. But all that is to come in the endless future, not this single moment Ingres selects as their downfall. Gowing noted Ingres’ work has always been so controversial, (12) and this painting is no different. If this is a Romantic operatic tragedy orchestrated by Ingres – it has indeed fueled music by many composers, producing no less than eighteen different operas between 1823 and 1914 – there is something of caricature lurking as well in the painting, where the typical Ingres curves of rounded faces contrast against the long angular lines of a passive Francesca and a striving Paolo, neither any more realistic than the fantasy they were pretending to model and blame on a book, as if love were a mere literary impulse.

Notes:

(1) Occupying Ingres for 40 years, this vignette was painted or sketched at least three other times later, including other similar paintings in the 1830’s and again in 1856 (note the smaller, 26 x 21.5 cm, Paolo and Francesca canvas recently auctioned as Lot 26 by Sotheby’s New York in 2007). Also see the Wildenstein Institute, Paris, catalog raisonné, Georges Wildenstein, The Paintings of J. A. D. Ingres, London: Phaidon Press, 1954, 1956 (second revised edition, third forthcoming).

(2) Vincent Pomarède and Chrystel Martin, Musée du Louvre, “Paintings in the Troubadour Style: 1806-24, Rome and Florence” INGRES (http://mini-site.louvre.fr/ingres/1.4.2.4_en.html).

(3) Marion Meade. Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Biography. New York: Penguin, 1991, 13, 170, 251-253.

(4) Teodolinda Barolini. “Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender.” Speculum 75.1 (2000) 1-28, esp. 1-2. Barolini also underscores that Francesca’s family became Dante’s later hosts in Ravenna in the person of Guido Novello da Polenta.

(5) Allen Mandelbaum translation.

(6) In 6.190 Virgil first uses columbae (doves) as “his [Aeneas] mother’s birds”.

(7) Virgil notes “the foul jaws of stinking Avernus” in 6.201 ff. (ad fauces grave olentis Averni).

(8) D. T. Moore. “Sir William Hamilton’s volcanology and his involvement in Campi Phlegraei” Archives of Natural History 21.2 (1994) Edinburgh University Press, 169-93; Ian Jenkins and Kim Sloan. Vases and Volcanoes: Sir William Hamilton and His Collection. British Museum Press, 1996.

(9) Mandelbaum translation

(10) Genesis 4:1-16.

(11) Mandelbaum translation

(12) Lawrence Gowing. Paintings in the Louvre. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 1987, 616.