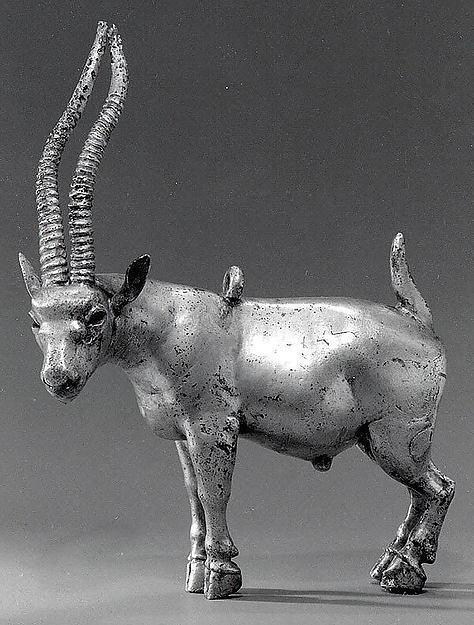

Proto-Elamite Reclining Gilded Silver Mountain Goat, 3100-2900 BCE, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 7 cm length (image public domain)

By Patrick Hunt –

How early in ancient art does realism appear? While many ancient cultures transitioning from the Copper Age to Bronze Age in the Ancient Near East and elsewhere did not directly imitate nature or imply realism in their visual canon of art, the Proto-Elamite Culture (circa 3100-2900 BCE) east of the Tigris River in the Zagros Highlands and around ancient Susa rendered wonderful realism in hybrid animals that elicit astonishment in the modern world.

Bulls, goats, rams and other herd animals with horns have been thematically abundant in the Ancient Near East, especially around the Iranian plateau circumscribed by the Zagros and Elbruz Mountains and multiple deserts. But the detail with which the Proto-Elamites invested their small metal sculptures continues to surprise viewers.

One silver animal image from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, amply illustrates the realism of hybrid creatures (a bull man) where an anthropomorphic dressed kneeling figure has bull arms and head and holds a beaker or upright vessel, dated 3100-2900 BCE and 16.3 cm high. Whatever ritual symbolism may be implied is mostly unknown given the lack of decipherment of this culture’s script. Adorant or not, the aspect of kneeling and holding a vessel seems significant – especially by a horned animal – but no other conclusive interpretation undermines the likely religious meaning.

Proto-Elamite silver Kneeling silver anthropomorphic bull, Met Museum NY, 16.3 cm high (image public domain)

Another equal impressive Proto-Elamite silver figure – top image- from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts adds the apparent subtlety of expressing character, wisdom and even possible whimsy. This silver mountain goat, also from Susa circa 3100-2900 BCE, has gilded elements in its human-like beard and even has one hoof tucked under in linear detail on its base, showing it was meant to rest flat against a surface. Is there an upturned half smile? If so, it might be the most telling feature because it seems to imply humor or self-sustaining wisdom.

Top: Proto-Elamite Mountain Goat, ca. 3100-2900 BCE, Boston MFA, Bottom:Underside of Mountain goat Boston MFA, 7 cm long (images public domain)

Yet another Metropolitan Museum of New York silver figure from the Proto-Elamites (also roughly circa 3100-2900 BCE) is an Antelope (or Ibex) Pendant at 4.02 in. length. The antelope-ibex horns even make an impressive aesthetic element on their own.

Silver Antelope-Ibex figure, Proto-Elamite (also roughly circa 3100-2900 BCE) Metropolitan Museum of New York, 4.02 in. l

But despite these unusually early accomplishments of casting silver objects – with the requisite additive process of molten silver – the most distinctive Proto-Elamite sculpture is not silver and is instead subtractive stone sculpture, in this case limestone. In a private collection in the UK, the exquisite limestone sculpture known as the “Guennol Lioness” (also circa 3100-2900 BCE), possibly from Susa, is the epitome of animal-human hybridity. Its upright bipedal stance – although missing its legs below the thighs – and “hand-clasp” (does it share features of both hands and clawed paws?) are somehow anthropomorphic while its animal nature is leonine; its face and “body language” also seem to bear emotive facial details that also evince regal dignity and possibly something deeply human.

“Guennol Lioness” Limestone. Proto-Elamite circa 3100-2900 BCE, Private Collection UK (image in public domain)

This stone masterpiece is not a horned animal but rather a predator yet not the least engaged in predation nor possessing what we can recognize as a predatory “look”. There may have been glass inlays in the eyes to underscore the natural realism, although a creature that seems not to exist given its non-animal stance. Hybridity itself so often appears to be a harbinger of the supernatural in antiquity almost regardless of culture, and these Proto-Elamite sculptures are certainly evocative of living combinations that because they are not natural are thus more likely to be supernatural. The irony is that we know so little of Proto-Elamite culture and language, but these few sculptures by themselves may be symbolic of some relationship between natural and less encountered worlds of the imagination. How advanced the Elamites were in their animal realism relative to their contemporaries (who seem incapable of such artistry) remains elusive, but these metal and stone sculptures aesthetically represent a culture that also largely remains a mystery.