Medici Maiolica Armorial Plate, 16th. c. (image V&A)

By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Alessio Assonitis & Brian Sandberg, eds. The Grand Ducal Medici and their Archive (1537-1743). London/Turnhout: Havey Miller Publishers/Brepols, 2016.

Over almost 30 years, the Medici Archive Project (MAP) – from its humble beginnings in the Florentine State Archives during the early 1990s to its present global reach on-line – has been able to open up the astonishing wealth of documents that remain of the Medici. The Medici’s attempts to gain power and influence in Florence, Tuscany and elsewhere both before and after they were ennobled and started to rule officially over Florence in the 1530s during a period that saw massive changes, discoveries and conflicts can be observed first hand by consulting the documents preserved in the archives and made available by MAP. Whereas before, as some of us still remember, it was extremely difficult to figure out, which documents from the different fondi to order and where to start one’s research, these days many of these “technical” problems are largely overcome and it is possible to concentrate on reconstructing the background of a particular historical event or on deconstructing time-honoured myths.

MAP, however, has done much more than providing much of the raw material that we all need for our research. It has brought together scholars as fellows of a post-doctoral programme and it has held international conferences in Florence that have facilitated the exchange between historians of all types with an interest in the Medici as politicians and patrons. And, it has prompted a turn of research focus that until a few decades ago often gave preference to the republican Medici of the fifteenth century at the expense of the Medici dukes and grand dukes who were somehow seen as second rate. For good reason, Eric Cochrane still called the time between 1527 to 1800 “the forgotten centuries” in the title of his 1973 book (Florence in the Forgotten Centuries 1527-1800, Chicago) on ducal and grand ducal Florence. How much of a misconception this was and how much of continuity persisted from one form of government to the next is attested not least by the present volume that includes 16 essays by former MAP fellows and present members of staff. Together they throw very interesting spotlights on a range of diverse topics from politics to medicine and with a geographical reach from the Old to the New World. Rather than discussing the essays one by one, I decided to look for themes and innovative approaches made possible by studying the extraordinary mass of papers preserved in Florence and made accessible by the work of MAP.

There were moments, when Florence and Tuscany could have become part of the Holy Roman Empire – then the most powerful political entity in Europe – but the duchy managed to stay “independent” of sorts, however closely it was associated with the empire. It needed to entertain close connections with the empire and through it to Spain, then a major military presence all over the Italian peninsula, and with Spanish colonies in the Indies. The records in the archives give an idea of how annoying such a close but forced relationship proved to be for Florence and to the Medici dukes and grand dukes. Nonetheless, it was kept alive by diplomatic contacts, including a network of spies, by cultural exchange and cemented, not least, by (imperial) dynastic marriages from Duke Alessandro de’ Medici onwards.

Therefore, it seems natural that the themes discussed in the essays fall, essentially, into two (interconnected) parts: Florence’s uneasy relationship with the empire and the roles and opportunities given to and taken by women in Medici Tuscany. In particular, the number of chapters focusing on women attests to the possibilities archival research offers to scholars trying to gain a better understanding of groups of the population rarely given much room in historical research, such as women and minorities or, of those who perhaps wished to remain in the shadow at the time. It is particularly interesting to see that women at the time, as duchesses or artists/artisans, sought knowledge and professional qualification and were self-confident enough to use it. The emphasis of the essays, however, is mostly on the second Medici duke and future first grand duke of Tuscany, Cosimo de’ Medici, son of a granddaughter of Lorenzo il Magnifico and of the military hero Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, and on his sons and successors. This attention on Cosimo, however, is used to branch out into themes long overdue for discussion or at least somewhat unusual in their approach. The short essays, many of them part of larger research projects, thus not only shed new light on old puzzles, they also make abundantly clear that and why a “proper” biography of the first Grand Duke of Tuscany remains a major desideratum.

Therefore, it seems natural that the themes discussed in the essays fall, essentially, into two (interconnected) parts: Florence’s uneasy relationship with the empire and the roles and opportunities given to and taken by women in Medici Tuscany. In particular, the number of chapters focusing on women attests to the possibilities archival research offers to scholars trying to gain a better understanding of groups of the population rarely given much room in historical research, such as women and minorities or, of those who perhaps wished to remain in the shadow at the time. It is particularly interesting to see that women at the time, as duchesses or artists/artisans, sought knowledge and professional qualification and were self-confident enough to use it. The emphasis of the essays, however, is mostly on the second Medici duke and future first grand duke of Tuscany, Cosimo de’ Medici, son of a granddaughter of Lorenzo il Magnifico and of the military hero Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, and on his sons and successors. This attention on Cosimo, however, is used to branch out into themes long overdue for discussion or at least somewhat unusual in their approach. The short essays, many of them part of larger research projects, thus not only shed new light on old puzzles, they also make abundantly clear that and why a “proper” biography of the first Grand Duke of Tuscany remains a major desideratum.

Apart from providing a highly revealing glimpse into the duke’s – but not only – character, political modus operandi, independent thinking, minute as well as decisive interventions if necessary, appreciation of public education and private reading matter, there are several substrata of investigation and information that come to light from the documents as well as in the essays. Perhaps the most striking are the power of networking, the question of identity and the importance of private libraries for the assessment of public figures such as Duke Cosimo and his father in law, Don Pedro Alvarez di Toledo.

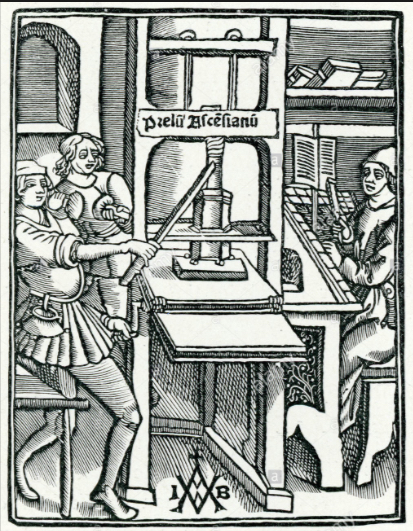

Printing circa 1511 (image in public domain)

Today, networking is something we all do and we all have to do. It is made easy by technical devices and the almost instant delivery of messages to almost everywhere around the globe. Between the sixteenth and the eighteenth century, i.e., the time frame discussed in the volume, the need was obviously there, but the means were difficult to operate, slow, and unreliable in their delivery. In a way it is lucky for research, for it means a considerable paper trail is still available that bears not only official communications but also the more private, even secret commentaries scrawled on the margins of letters and reports. For all the technical problems existing at the time, Florence managed to stay connected with the Holy Roman Empire but also with other places in France, on the British Isles, elsewhere in and outside Europe, remarkably well. A huge cast of diplomats and/or spies was sent out with precise instruction to conduct missions for the (Grand) Duchy and to report to the (grand) ducal court on everything remarkable or strange they might encounter. Perhaps the most important relationship was that to the Empire and Spain, since Florence depended so much on it. Nonetheless networking with the French or with the smaller, sometimes less reliable centres within the Empire helped to balance the overpowering weight of the Empire in political or military matters concerning Italy or Tuscany – for example in the punishment of Lorenzino or during the Sienese War. Information was power then as much as it is now and the papers preserved indicate how great a store Medici Florence set by networking and gathering information.

Duomo of Florence, circa 1436 (Photo P. Hunt, March 2013)

Identity is another issue to be addressed in any research concerning a court operating on such an international level. Cosimo I and his immediate family had ceased to be “only” Florentine. Even his forebears had occasionally married outside the city’s oligarchy but the duke’s predecessor Alessandro and Cosimo himself had made major international matches. Such weddings made the emperor the father in law of the first duke and a leading Spanish family became relatives of the second. By means of such family ties information, customs, language and cultural preferences were exchanged both ways but also family members, for example, Eleonora’s brother, Don Luis, and her father, Don Pedro, spent time in Florence and influenced court life. Two of the essays show, among other things, that even though we still seem not to be sure whether Don Luis was Eleonora’s older or younger brother, the correspondence and documentary evidence preserved now give a much better idea of Don Luis’s education, his plans and career.

Many foreigners, whether they were part of the ducal family or not, contributed to the cultural, political and – not least – to the economic life of Florence and Tuscany. In many cases, we can see from their names that they belonged to ethnic or religious minorities but that does not always determine their true identity or solve exactly where they came from and what kind of claims they may have had “back home” or in Florence. It is interesting though that Medici Florence entertained relationships, even friendships with people of all origins at a time when this could have been difficult, even dangerous.

In many other cases, the names of foreign artists, artisans and publishers had often become “italianised” for so long that only recently researchers started to think about them as not Florentine. Torrentino, Stradano, Giambologna and many others contributed to making and keeping Florence a centre of artistic production. They were responsible for masterworks in sculpture, painting and architecture, they installed new branches of “industry”, for example book printing and tapestry making, in Florence and without them the fame of Florence would have quickly faded as a quiet backwater in the shadow of the empire.

Finally, the dukes and grand dukes of Florence had their own identities to develop and to broadcast before, during, and after holding office. Each of them had more than one persona in which to change in accordance with requirements. In the papers they left behind, we can meet multiple Cosimos, Francescos and Ferdinandos – to name just the first three Grand Dukes – who presented themselves as politicians, as entrepreneurs, as members of their households and courts with diverse voices and personalities. Thus from the documents we can learn how they addressed the business of ruling, what they really thought about their peers, and how much they may have been so far misunderstood owing to past deference or modern prejudice.

Part of their personality can be gleaned from their inventories, which trace possessions of all kinds but in particular their collections and the context, access and display provided to and for them. Even those who do not share Josephine Tey’s maxim that the truth is always in the account books (Daughter of Time) will find it interesting to see what the Grand Dukes collected. They will be curious to find out at which point in their career Cosimo and his successors and their female relatives started to collect particular categories of objects, how the collection was displayed and how much they were prepared to pay for a particular piece. Libraries were part of such collections and long lists of books are provided in the guardaroba inventories of Palazzo Vecchio. We understand that Cosimo was a bookish duke, someone who not only read and wished to be kept up to date on news, discoveries and research, but who also went after entire book collections when they became available. He was eclectic in his reading and he was independent enough in his thinking to read books that would not have been advisable and advised reading matter in the days of the papal Index of Forbidden Books. No wonder, perhaps, that he told his agents to burn scrap paper on Piazza Santa Croce when the Index came out to satisfy the pope and not to damage the booksellers. Studying the composition of the libraries of Cosimo and his peers can thus provide additional information that has probably been overlooked at our own peril for too long.

MAP Intern 2015 (photo courtesy of Caitlin Petty MAP Intern 2015)

Probably the Medici Grand Dukes and their administrative staff did not foresee the growing enthusiasm for their letters and record circa 500 years after they were written. They would not have imagined that international researchers would have studied every word written by, to and for them with nit-picking attention to find out more about the running of the court, about the political networks and the Grand Dukes’ and Duchesses’ most private plans and successful intrigues. One could speculate how much they might have appreciated the possibilities of a database and of the internet. By carefully keeping and filing away their documents and by making copies of those letters sent out into the world, however, they did everything possible to ensure that “written words remain”.