Fig. 1 Thomas Rowlandson, “Bath Races”, ca 1810, (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich)

Fig. 1 Thomas Rowlandson, “Bath Races”, ca 1810, (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich)

By Cher Beall –

Art in Britain during the Georgian period (1714-1830) is characterized by sophisticated oil paintings of landscapes and well-lit portraits by world renowned artists including J.M.W. Turner, Joshua Reynolds, and Thomas Gainsborough. The ink and watercolor drawings of English artist and caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) stand in contrast to the purpose and style of the time. This can be immediately appreciated in his “Puss in Boots” (Fig. 2 below) where he satirized army camp life and the mores of Napoleon’s field officer General Jean-Andoche Junot, 1st Duc d’Abrantès at the height of the Napoleonic Wars when British loved to lampoon French bellicosity. Not only did Rowlandson demonstrate a preference for different materials, he choose the everyday life of all Londoners as his subject matter. Through his detailed art, Rowlandson provided an unintentional abundance of information that is incredibly important for the historian of art and culture and quite significant because he may have been the most accurate documenter of life in London over a period of almost half a century. Consequentially, it is from Rowlandson that we learn the most about anthropology of the era. We are fortunate that he was so acutely attuned to the pace and pulse of the world around him (Meier, 9).

Fig. 2 Thomas Rowlandson, “Puss in Boots: or General Junot Taken By Surprise”, 1811 (private collection)

Possessing an undeniable talent for capturing the timeless eccentricities of social archetypes, Thomas Rowlandson earned his fame creating satires and caricatures. Much of his comic art speaks to the ageless conditions of human character and behavior. This ability to ascertain and convey the subtleties of human nature through his art is one of the many reasons we delight in his creations. It is as though he has just shared an intimate, private joke. We are aware that he has seen what we have seen, but dare not say. It feels like an instant of recognition, followed by a moment of direct eye contact. Words are not needed. We should honor this astute awareness, and be astounded at the brilliance and manner in which Rowlandson was able to capture and artistically execute his message. We can delight in the apparent amusement of the artist expressed through his renderings, and be thoroughly beguiled ourselves.

It is this innate hyper-perception that allows Thomas Rowlandson, and his art, to offer so much invaluable insight into the life and mentality of late Georgian society. When studying history, we are often educated on the conspicuous: costume, architecture, design, and style of a period. Rowlandson, however, is able to provide a candid commentary on both the life and mentality of his time, on its activities, social norms, political climate, and even medical progress. His immense gift is that he is able to share all this historical and sociological information in an insightful, appealing, and amusing way. This brilliant artist and social observer conveyed a true sense of what it looked like and felt like to live in Georgian England.

His Art and Life

Thomas Rowlandson was one of the most talented British draftsmen, unsurpassed in his expressive flowing sinuous lines, and tactical use of watercolor. The magnificence in his pen and ink work is easily seen in his drawings across the genres of his career. His contemporaries were William Blake, known for his poetry and mysticism, and William Hogarth, for his extensively detailed satirical drawings. Among them, Rowlandson is incomparable in his relaxed, playful creation of renderings and his genius graphic placement of color.

At age 16, the talented Rowlandson became an art student at the Royal Academy Schools in London. In his early career, he was a portraitist as well as a master of rural picturesque landscapes. There are many preserved examples of his traditional drawings of demure pastoral settings or reposing river scenes. In the compositions in which landscapes or architecture serve as a background for the human figure, Rowlandson usually used two kinds of people of two different shapes. One was often unattractive, poorly shaped, frequently old, and the other was young, beautiful, and voluptuous. Contrasts and opposites are the structural principles in much of his work (Paulson, 25).

As a young artist, Rowlandson also began to create playful works like One Tree Hill In Greenwich Park, in which society ladies are rolling down a hill with their bottoms exposed. As Vic Latrell writes in his essay “Rowlandson’s London”, that “It was to happiness and pleasure that he responded. No other artist has depicted life’s feasts quite so zealously” (Phagan, 22).

Rowlandson’s output was prodigious; it is estimated he produced at least 10,000 drawings (Hayes, 11). He also illustrated approximately 70 books, including The Three Tours of Doctor Syntax, and became famous for the numerous playful renderings within (Savory, 17). However, it was Rowlandson’s comic art, caricatures of daily life, and political cartoons that best demonstrated his talent and abilities. He had an insightful view of the comedic potential in an action or situation (Wark, 8). One might suppose that in his rapid and prolific production of art for print, he had to fundamentally respond as his truest self. Due to the fact that many of these illustrations needed to go to press immediately for newspaper publication, he did not have ample time for refinement or review. Thus, he blurts out who he really is, and the result is utterly personal and brilliant.

Rowlandson was a man of pleasure. He was boisterous, full of laughter, and possessed a big spirit. His life, therefore, was lived unsurprisingly as a womanizer, hard drinker, and infamous gambler. By representing his own proclivities in his work, Rowlandson became a visual artist who portrayed human life in all its animalistic tendencies (Gert, xxii). This must have been repugnant to the Georgian British sense of propriety, and most likely would have encouraged the rebel in him more.

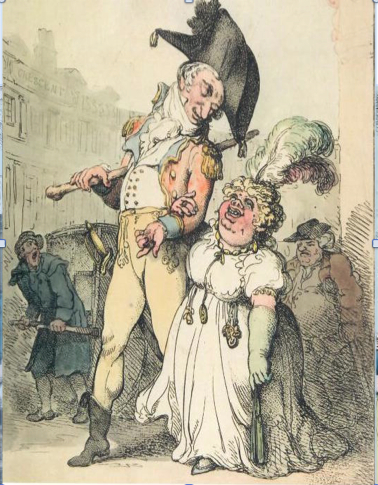

Fig. 3 Rowlandson, “Social Inequality”, ca. 1802 (public domain)

Social Life

Rowlandson’s drawings placed a strong emphasis on social interaction (Phagan, 11). He possessed a unique perspective on Georgian society and the crossing of class boundaries with regard to social life and leisure. In his renderings, social life is illustrated in various contexts: high society, politics, street encounters, taverns, clubs, outdoor entertainment, and sexual and romantic entanglements. Rowlandson also often sketched a range of social classes in his work, for example, the House of Lords, the gentry, shopkeepers, laborers, and farmers, as well as the different levels of society as they mingled in public arenas, parks, and the artistic venue of Covent Garden. This social hierarchy and its layers were a fitting target for the comedy that ensued when he mixed the ranks (Phagan, 12) (Figure 3 above showing a caricature of an officer with a lady of means but little attraction) or lampooned and absurdly enhanced physical differences (Figure 4, “Dr. Convex and Lady Concave”). This fits with what history tells us of the time because the 1790s witnessed a burgeoning respect for the middle classes and a disdain for the upper ranks. It is also important to note that Rowlandson’s art provided those of humble means as much visibility as the rich, as opposed to other artists of the time who were focused on painting portraits of the wealthy, in all their finery, amidst the backdrop of their tremendous estates.

Fig. 4 Rowlandson, “Dr. Convex and Lady Concave”, 1802 (courtesy of The Economist 1843)

In addition to his depictions of society, through Rowlandson’s drawings, we learn what leisure activities were popular at the time. We see that drinking, smoking, gambling, and carousing are quintessential Georgian past times and that coffee houses, pubs, and debate clubs were favorite haunts. We learn that get-togethers for the purpose of introducing chemistry experiments might be sources of entertainment. We see examples of public hangings, dog fights, and boxing. From the social scenes depicted, we also see various details about the latest fashions including wig styles, extravagant hats, and lace for men. We see recognizable, noted architecture as well as social gatherings for the elite and general public.

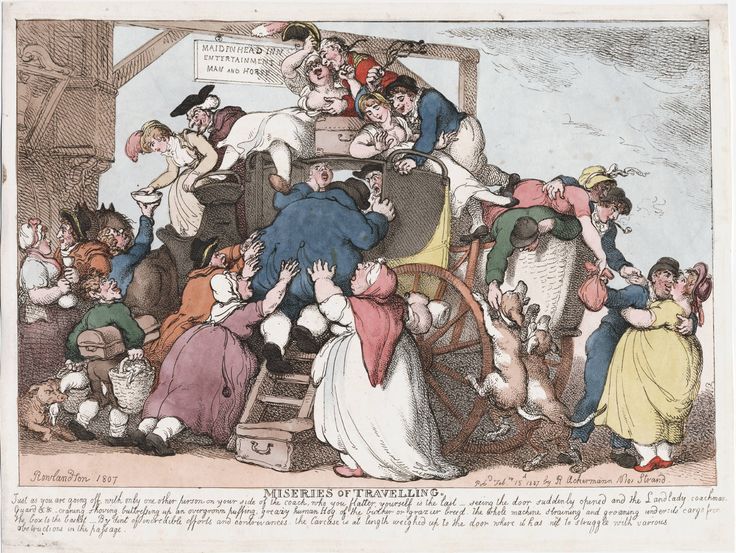

By the early eighteenth century, the Covent Garden area of London, where Rowlandson lived (Blake and Hogarth were also neighbors), had become London’s bohemian center. It was the home of artists, writers, printers, actors, courtesans, and numerous taverns. Rowlandson often depicted life within this enclave of London’s pleasure ground. In addition to the illustrated sites of fun and frolic, one sees images of crowded streets, broken carriages, and crime reminiscent of Charles Dickens or in Moll Flanders. Sewage in the streets and chamber pots were purposely illustrated to show imperfection, reality and the inconvenience of life in the 1700s, such as uncomfortable travel, with all his signature observation and wit (Figure 5 “Miseries of Travellers” below showing crowded public conveyance in the bumptious spirit of Pieter Bruegel the Elder). It appears that regardless of the subject matter, there is an abounding, insatiable gusto of enjoyment that pervades Rowlandson’s work (Meier, 12).

Fig. 5 Rowlandson, “Miseries of Travellers” 1807 (public domain)

Social Norms

In various artistic examples from the era, including the books Moll Flanders and Tom Jones, we see men marrying women for money and young women marrying old men for money. Rowlandson was no different. In his drawings, beautiful, voluptuous, young women are obsessively paired with old and unappealing men or a young woman with a man at the moment of his mortality (Fig. 6 “Gaffer Goodman” below).

Fig. 6 Rowlandson “Gaffer Goodman…” 1815 (public domain)

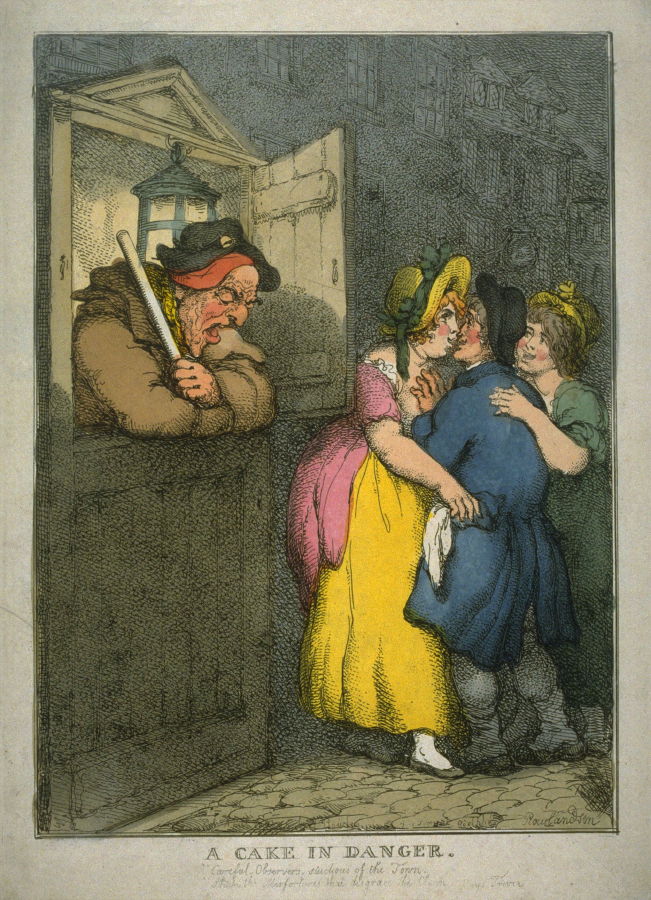

Prostitutes were pervasive in Rowlandson’s time. In the second half of the 1700s, the number of prostitutes increased dramatically due to the influx of women from rural areas moving into the city. Prostitutes roamed freely and aggressively in Covent Garden (Phagan, 83). Rowlandson approached the theme of prostitution in many ways, pointing to its temptations and pleasures throughout his artwork. (Figure 7 below) In the 1790s, he focused on high society men and expensive prostitutes. Later coincidently, when his own budget was tighter, he focused on street prostitutes. Rowlandson’s observations of society’s indulgent pleasures vibrate with social tension and personal irony, all of which contribute to the commanding intrigue of his work. (Heard, 15)

Fig. 7 Rowlandson, “A Cake in Danger”, 1806 (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

Medical Details

In addition to the social norms and reality of the times, Rowlandson’s drawings show us the horrors and fears of the era’s medical issues. We see drawings illustrating amputation, alerting our attention to what it must have been like during an era without drugs or anesthesia. We learn about the prevalence of gout and often see spots indicative of syphilis. We are introduced to medical fads, such as cupping. We see images of the antiquated practice of blood-letting. We learn about the popular trips to Bath for relaxation and health (Fig. 1 “Bath Races” above). We are exposed to the marvel of false teeth. We are also able to witness schools of anatomy, dissection rooms, and the pilfering of graveyards for bodies. There is a vast array of historical and sociological information that can be obtained through viewing Rowland’s comic artwork even when it is focused on gruesome health and medical issues, as seen in his caricatured personification of swollen Dropsy (Edema, possibly from congestive heart failure) and wasting away from Consumption (Tuberculosis) (Figure 8 below).

Fig. 8 Rowlandson, “Dropsy Courting Consumption”, 1810 (courtesy of Harvard Magazine)

Political Satire

George III and his family were favorite subjects of Rowlandson’s political satires. The rumored frugality of the king and that of his wife, Queen Charlotte, the extravagance and affairs of the Prince of Wales, and the supposed corruption of Duke of York all made popular dramatic illustrations.

Some of Rowlandson’s earliest and perhaps funniest political prints portray the rivalry and political campaign activities between politicians Charles James Fox (a Whig) and William Pitt the younger (a Tory) that shaped British politics in the mid 1780s (Heard, 57). Rowlandson was essentially an artist for hire, and worked for both sides, prolifically producing satiric art for both political campaigns. During one political campaign, the Duchess of Devonshire was a favorite of the public, as well as one of Rowlandson’s popular political subjects (Figure 9 below).

Fig. 9 Rowlandson, “The Devonshire, or Most Approved Method of Securing Votes,” 1784 (Met. Mus. New York)

This was likely because she was beautiful, but also because this was the first time that women were taking an active role in politics. Rowlandson created many humorous political prints involving the Duchess, who campaigned in support of the political candidate Fox. Criticism of her involvement in the election was based on the fact that she was female; it was considered reprehensible for a woman to canvas in such a manner (Heard, 71). This also applied to the Countess of Buckinghamshire, Albina Hobart, although rather than attack her honor, they attacked her figure. Rowlandson’s political drawings communicate the realities of the time at a mere glance, whereas they tend to be buried deep in history books.

Caricature of Sexuality

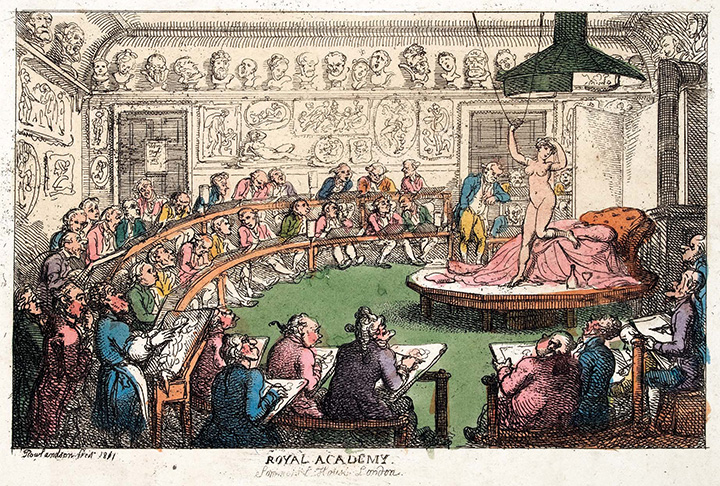

Rowlandson was at the Academy Schools when certain artwork was censured by academics for “insufficient drapery” on drawings of Adam and Eve. In 1790, a copy of the classic sculpture, Apollo Belvedere, created outrage because it offended female modesty. It was thought by those that censored, “Nudity, and even the representation of erotic acts, could be tolerated allegorically or mythologically, but it must not please as nudity, as sensuality” (Gert, xvii). Rowlandson found this hypocritical and repressive (Phagan, 31). He clearly believed in the healthy enjoyment of the senses. Perhaps this is why he often illustrated the classic nude sculpture (which was somewhat permissible) with his own less modest cartoon nude (Figure 10 below, “The Royal Academy: A Life Class”) In his way, he mocked the rules and prudish societal restrictions.

Fig. 10 Rowlandson “Royal Academy: A Life Class” 1811 (The Royal Collection, UK)

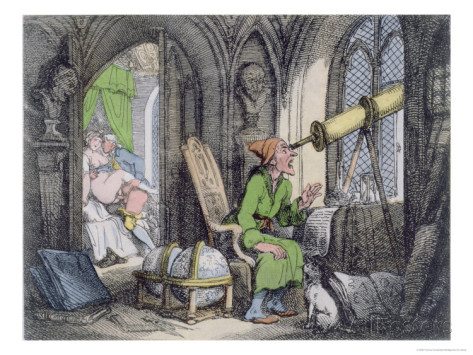

Rowlandson’s erotic prints seem shocking for the Pre-Victorian time period. His explicit drawings certainly imply expertise and knowledge by graphically depicting a variety of sexual positions. As Amelia Rauser writes in her essay “Amoral Humor: Desire and Mockery in Rowlandson’s Comic Art”, that “Rowlandson’s watercolors paint a chaotic and lusty picture of eighteenth-century England” (Phagan, 45). Sex, and perhaps the comedy of sex, seemed to absorb Rowlandson, a departure from the general attitudes and values of his time. Rowlandson viewed the chastity of the Georgian era as sexually repressed, and in reaction, he personally and artistically rebelled against it. Sex was a consistent theme in his work, perhaps an exaggeration of an idea, incident, or even his fantasies. “There was something compulsive in his repeated depiction of the seductive or voyeuristic relationships of grotesque old men and busty young women, or of the traitorous triangle of young wife, young lover, and old husband” (Phagan, 28), for example, in the cuckolding of old preoccupied men (Fig. 11 “The Distracted Astronomer” below).

Fig. 11 Rowlandson “The Distracted Astronomer” ca 1808 (public domain)

Even when his drawings were not explicit, sexual innuendo permeated them, usually coupled with some sort of mockery and mirth. This appears to be one area that is more revealing about our artist than the general culture and history of Georgian England.

Conclusion

In Great Britain in the Age of Reason, through reading and study of art and history, we can enjoy an interdisciplinary study of the 1700s and early 1800s in England. With the additional examination of Rowlandson’s extensive artwork collection, we can discover a great deal of visual and social commentary on this alluring era in British history. The blend of perception, wit, and skill in which Rowlandson portrayed the life and mores of his time was uniquely his own (Riley, vii). His art is interesting to us today as compelling, beautiful, and comedic illustrations that also function as tremendously revealing cultural archives. In the words of author and Rowlandson scholar, Kurt von Meier: “He came right up close against the world, and chose to stay there’all the better to feel it alive and grow and change, and ultimately to die. That is what his art is all about: the world of England, especially the boisterous London of George III and the regency-from the late eighteenth century up until his death just ten years before Queen Victoria ascended the throne, when finally the spirit of that whole period faded away.”

Works Cited

Grazie, Galanterie, Groteske. Thomas Rolandoson (Hannover,Wilhelm-Bush-Gesellschaft, 2001) 19,25,33,41,52,76,117

Haslam, Fiona. From the Hogarth to Rowlandson Medicine in Art in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Liverpool: UP, 1996) 177, 225, 249, 273, 281, 283.

Hayes, John. The Art of Thomas Rowlandson (Alexandria: Art Services International, 1990) 11-13, 76, 108, 170, 172.

Hayes, John. Rowlandson Watercolors and Drawings (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1972) 11, 60, 197.

Heard, Kate. High Spirits: The Comic Art of Rowlandson (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013) 10,15,16,18,19,60,72,77,97,103,18,250.

Meier, Kurt Von, Ph.D. The Forbidden Erotica of Thomas Rowlandson (Los Angeles: Hogarth Guild, 1970) 89, 101, 123, 131, 177.

Paulson, Ronald. Rowlandson: A New Interpretation (New York: Oxford UP, 1972) 25, 26, 28-30.

Payne, Matthew and James Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson: His Life, Art and Acquaintance (London: Hogarth Arts, 2010) 238, 239.

Phagan, Patricia. Thomas Rowlandson: Pleasures and Pursuits in Georgian England (London: Giles, 2011) 11-14, 22,31,45 83, 91.

Riley, John. Rowlandson Drawings from the Paul Mellon Collection (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1977) Preface.

Rowlandson, Thomas. A Catalogue of Books Illustrated by Thomas Rowlandson (New York: Grolier Club, 1916) VIII, IX, 9, 10.

Rowlandson, Thomas. Thomas Rowlandson: Grazie, Galanterie, Groteske – Englische Bildsatire Zwischen Rokoko Und Romantik (Hannover: Wilhelm- Bush- Gesellschaft, 2001) 19, 25, 33, 41, 52, 76, 117, 201.

Savory, Jerold J. Thomas Rowlandson’s Doctor Syntax Drawings (London: Cygnus Art, 1977) Introduction, 17, 43.

Schiff, Gert. The Amorous Illustrations of Thomas Rowlandson (New York: Cythera, 1969) XIX, XX, XXI, XVII,XXII.

Wark, Robert R. Drawings by Thomas Rowlandson in the Huntington Collection (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1975) 2, 10.