Matisse, The Serf, MOMA San Francisco (images courtesy of MOMA)

By Alice Devine Wilson –

At first glance, modern art seems to have little connection to antiquity’as contemporary art, by its definition, departs from the past. However, many modern artists of the twentieth century root their creations in ancient traditions. French Post-Impressionist Henri Matisse and his sculpture, the Serf, serves as one such example. In fact, when German armies swept through France in 1940, Matisse left his own work behind in occupied Paris, taking with him only his prized possession, a Roman copy of a Greek original marble torso of a young girl. Modern artists such as Matisse, with his use of the traditions and practices of ancient sculpture, form an undeniable link to the past.

The Serf

Housed in San Francisco’s recently renovated Museum of Modern Art, Matisse’s bronze The Serf, dated 1900 to 1903, measures just over three feet tall and slightly more than a foot in width. The bearded man stands arrested, his eyes cast down at the ground, his truncated arms by his side. The body appears somewhat compressed, with muscular limbs. And, the rough molded bronze creates an uneven texture over the entire piece, similar to heavy impasto of some paintings. Like his lowly title, the Serf seems connected to the land by his bowed head, the heavy appearance of his molded body, and bronze crafted from alloys of the earth. The dark bronze color evokes the dirt the Serf may cultivate as occupation. While the modeling appears modern, Matisse’s Serf pays homage to ancient Greek and Hellenistic sculpture with classical elements of anatomical representation, rounded view, materials, and method.

One might argue that Matisse’s portrayal of a lowly serf does not relate to refined ancient Greek sculpture. Matisse’s piece tells neither a story of an athlete nor mythology. And, the Serf’s compressed body lacks the elegance of Greek idealized human form. Finally, its rough surface suggests a beginning sculptor rather than an accomplished master of the ancient world. However, Greek sculpture does indeed portray everyday people in pedestrian tasks. More importantly, the underlying attempts to represent man and his character unite works of ancient art with this modern sculpture. As Greek mythology sought to explain natural mysteries, so did Matisse try to discover “the essential character of things” and to produce an art “of balance, purity, and serenity,” as written in his “Notes of a Painter” in 1908. In representing his subject, Matisse turns to the precedent of ancient Greek sculpture with its distinctive characteristics.

Hellenistic Sculpture Tradition

Hellenistic art refers to the period of antiquity, generally between Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE and the Roman conquest of Greek world, roughly 146 BCE. Classical Greek sculpture, in the era prior to the Hellenistic period, idealizes the human form, especially with gods and athletes. In contrast, the Hellenistic artists display the human condition in its various forms of motion and emotion, beauty and plainness, triumph and struggle. The Greek notions and practices of sculpture spread to the Romans, who continued these trends in their own work as well as via copies of original Greek sculpture.

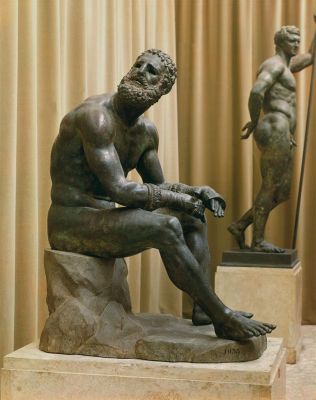

Like the Classical and Hellenistic sculptors who value realistic anatomical representation, Matisse shows “a deep interest in the human figure,” according to The Art Institute of Chicago. While well-known sculpture such as Myron’s Discobolus (discuss thrower) display elegant beauty, Greek sculptors also portray the commoner: a fisherman, a drunken woman, an old woman crouched with age, and various animals. Similarly, Matisse pays attention to the human body, although in a more exaggerated, nearly grotesque manner. When Matisse sculpts muscular shoulders and legs next to a large belly, his work becomes more like the Greek sculpture of a boxer with his defined muscles and flattened nose, a casualty of his sport. The Serf‘s recognizable human figure, with muscles and tendons’although rougher than the Greek style’conveys both realistic anatomy and a station in life.

Posing In The Round

The Hellenistic period emphasizes dynamic sculpture “in the round”, that is, art visible from all sides. In order to amplify this trait, the ancients cast subjects in supple motion: walking, leaning, shooting, drinking, eating, lounging, flirting, fishing, and napping. By arresting subjects in three-dimensions, sculptors capture a moment in time. Moreover, the use of diagonal line and twisting motion create a sense of vitality. Matisse mimics this technique, as his serf seems to be caught mid-stride; one leg extended from the other. The Serf’s head bends down in contemplation or resignation. The thick molding, downcast head, and slumped shoulders reveal the Serf’s emotional heaviness. In the same way that mythological reference and pose tell a story, so too do facial expressions add to the artist’s expression of emotional state.

Torso of a Youth (“The Vani Torso”) (detail), Colchian, 100–200 B.C. Bronze, 41 3/4 in. high. Georgian National Museum, Vani Archaeological Museum-Reserve. Photo: Rob Harrell, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Like today’s “selfie” photographic popularity, the Greeks also appreciated a fine portrait. To that end, Greek sculptures incorporate distinguishing canonic features’large noses, receding chins, and deep-set eyes’that viewers understand to be a specific individual. Matisse’s subject too, with his beard and stocky physique, would be recognizable in a French village filled with men, women and children of various shapes and sizes.

Method

Matisse’s use of bronze as material reinforces his reference to ancient tradition. Bronze, mostly an alloy of copper (Cu) and tin (Sn) whose proportions are generally around 85% Cu and 15% Sn, has been prized since the beginning of the Bronze Age, roughly early 4th millennium BCE. The earliest tin bronze allowed for a stronger material, easy to cast and mold. Evidenced by surviving Greek artifacts, much later the ancient Greeks around the Archaic Period ca by 750 BCE regarded bronze statues as the highest form of sculpture, although many of the famous Greek bronze sculptures survived only as Roman copies in marble. According to the Getty Museum, “The Roman historian and written Roman historian and writer Pliny distinguished between two types of patinas. Aerugo nobilis (stable bronze, or rust)” and the destructive “Virus aerugo (vile or virulent patina)” Pliny’s writings serve as valuable evidence that bronze was indeed a used and valued material for ancient sculpture.

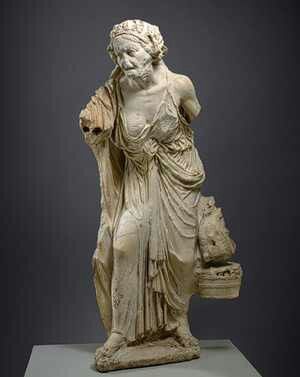

Old Market Woman, c. 150-100 BC, marble, h. 1.257m, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Roman marble copy of Hellenistic bronze (image courtesy of MMNY)

In addition to material, Matisse’s casting methods utilize both sand casting (a recent 19th century technique) and lost wax, a technique that has existed since ancient times. To illustrate, The Art Institute of Chicago has used technology such as plasma-optimal emission spectroscopy and x-radiography to analyze the alloy content and casting method of the Serf. Matisse’s lost wax casting involves creating a duplicate metal sculpture from an original (wax) cast, and imparts a high level of detail to sculpture. This ancient method has been documented in excavations as early as 4500 BCE. In contrast, sand casting forms molds with sand and clay into which molten materials are poured. Lost casting is ancient, precise, and expensive while sand casting is more economical and typical of a foundry. In melding these two techniques’ancient and merely old’Matisse fuses the modern with antiquity.

Parts of a Whole

In 1972, when divers pulled two fully intact bronze sculptures roughly dated 450 BCE from the sea near Riace, Italy, archeologist’s eyes widened. The discovery of the Riace Bronzes – now housed in Museo Archeologico Nazionale Reggio Calabria – became heightened by the nearly intact large bronze figures, fully conserved after resting on the bottom of the sea for over two and a half thousand years. Thousands of years after their creation, artworks are expected to have broken. Yet, these missing pieces seem to enhance, rather than diminish, artistic expression. While the Riace Warriors are remarkable, so too, are the partial sculptures that have survived since antiquity. We have learned much abut lost wax casting and bronze making techniques from the conservation of these Rice Bronzes and others less complete. For example, although the famous Venus di Milo sculpture lacks full arms, viewers imagine elegant limbs that accompany her graceful form. Matisse also discovered “that it was unnecessary to represent the entire body to capture a form, a movement, a spirit, or an emotion, a lesson learned through the beauty of accidentally fragmented sculptures from the ancient world,” according to Caterina Pierre. Thus, Matisse revised his Serf sculpture by cutting the full arms of the bronze to truncated limbs. Matisse’s imitation of an ancient piece of art manifests itself in the sculpture’s fragmented arms, a nod to the Greeks.

Seated Boxer, c. 5 BC, bronze, h. 1.28m, Museo Nazionale Romano (image courtesy of Museo Nazionale Romano)

What is Old is New Again

Originally trained as a lawyer, Matisse adopted the practice of studying a long precedent in bronze by looking to works of antiquity to explain the nature of our human condition. Perhaps the ancients and Matisse would have agreed with the observation made in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Like human evolution, perhaps all artistic expression contains some iteration of the past. In Matisse’s case, the link to ancient Greece remains clear and recognizable, regardless of a particular work’s “modern” classification.

Bibliography

Albert Edward Elsen. The Sculpture of Henri Matisse, New York, Abrams, 1st ed. 1972

Geoffrey Hendricks. From Sea to Sky: Recasting the Riace Bronzes. Cologne, Taschen, 2005.

The Art Institute of Chicago. “The Serf.” The Art Institute of Chicago. Last modified October 27, 2016. Accessed October 27, 2016. http://www.artic.edu.

“Bronze-patinas-noble-and-vile.” The Getty Museum. Accessed October 20, 2016. http://www.getty.edu.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. New York City, NY: Scribner, 2004.

Matisse, Henri. “Notes of a Painter.” The Metropolitan Museum. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://www.metmuseum.org.

Pierre, Caterina. “Matisse & Rodin.” 19th Century Art Worldwide, October 2010. http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org.

“www.henrimatisse.net.” Accessed October 1, 2016. http://www.henrimatisse.net.

R. R. R. Smith. Hellenistic Sculpture (World of Art). London, Thames and Hudson, 1991.