Bronze Chimera of Arezzo, ca 400 BCE, Cosimo I Medici Estate, Archaeological Museum, Florence (photo P. Hunt, 2014)

By Andrea Gáldy –

WINCKELMANN, FIRENZE E GLI ETRUSCHI IL PADRE DELL’ARCHEOLOGIA IN TOSCANA, Archaeological Museum, Florence, 26 May 2016 to 30 January 2017.

Catalogue available in Italian and in German: Barbara Arbeid, Stefano Bruni, Mario Iozzo (eds), Winckelmann, Firenze e gli Etruschi. Il padre dell’archeologia in Toscana, ISBN: 9788846745187, edizioni ETS, Pisa 2016, pp. 344, ill.

and

Winckelmann, Florenz und die Etrusker. Der Vater der Archäologie in der Toskana, ISBN 9783447106382; Verlag Franz Philipp Rutzen, in Kommission bei Harrassowitz Verlag Wiesbaden 2016.

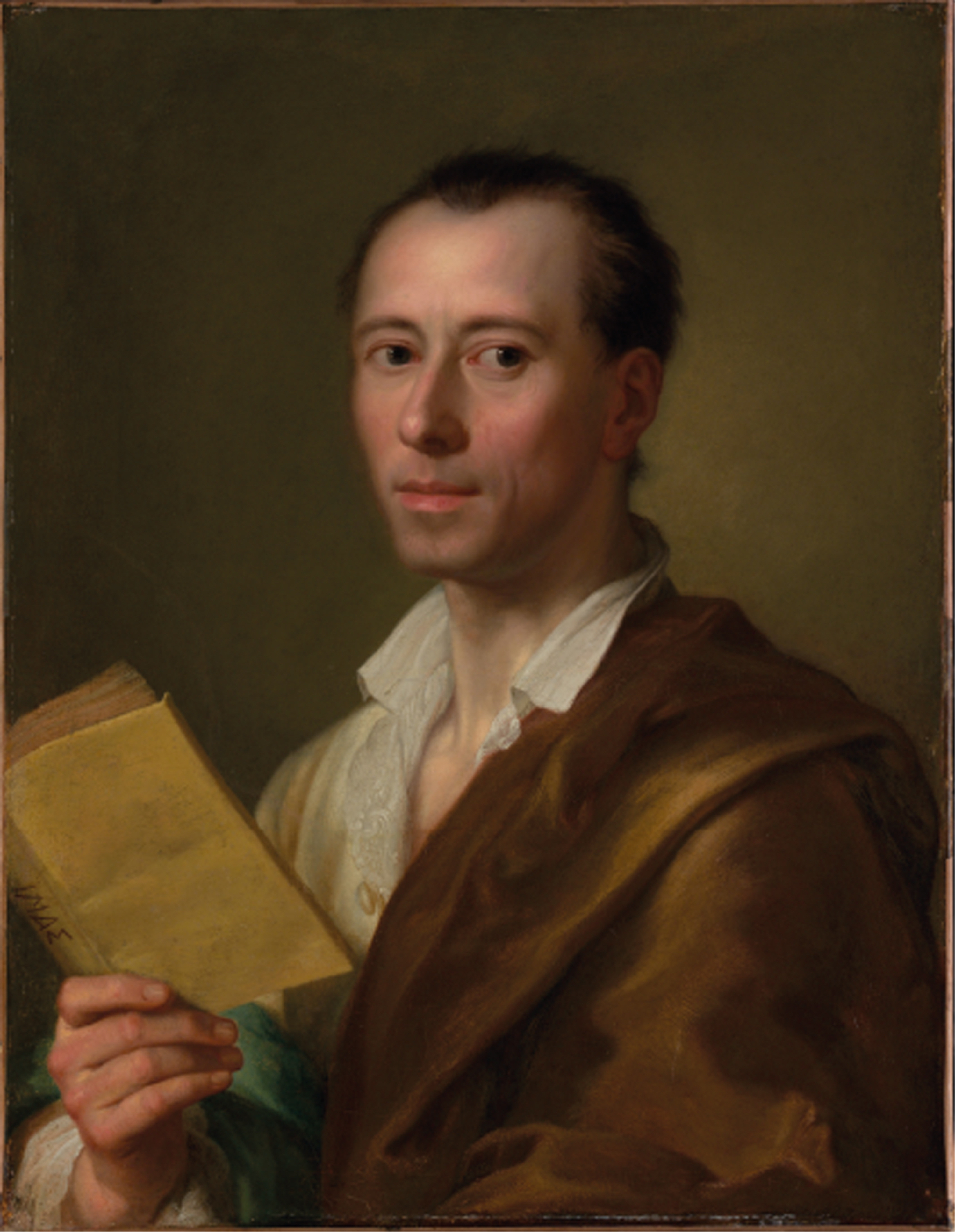

In 1755, Johann Joachim Winckelmann (b. Stendal, Germany 1717- d. Triest, Italy 1768) arrived in Rome for a life-changing visit that would also influence ancient art history and the history of archaeology to this day. Through the intensive study of ancient works of art, Winckelmann (Fig. 1) discovered the importance of Greek art and of its influence on Roman, Renaissance and Neoclassical art. He published his Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works (1755) as well as his History of Ancient Art (Geschichte der Kunst, 1764) and a range of historical essays on single works of art. Thereby he managed to establish an approach to ancient art history that was structured by an idea of linear progress perhaps not dissimilar to that of Giorgio Vasari a couple of centuries earlier.

Fig. 1 Anton Raphael Mengs, Portrait of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (New York, Metropolitan Museum, inv. 48.141), 1777

Fig. 1 Anton Raphael Mengs, Portrait of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (New York, Metropolitan Museum, inv. 48.141), 1777

What is perhaps less known and may even come as something of a surprise is the fact that Winckelmann also spent some time in Florence from September 1758 to April 1759 where he studied the antiquities once collected by the Medici and by other leading families of the city. In Florence, next to Greek and Roman antiquities, the works of the Etruscan had long played a considerable role in the collections of the ducal family and the study of Etruscan art, history and language had been encouraged at the court and in the academies of Cosimo I de’ Medici and his descendants since the sixteenth century (Fig. 2), since Medici collections of Etruscan antiquities were already famous (in addition to the Bronze Minerva, note the Bronze Chimera as lead image above). Even though this engagement with Etruscan remains had brought forth some rather adventurous “Etruscan Myths” about their ancient culture, such ideas continued and spread well into the eighteenth century. For example, in 1724, the manuscript of the first systematic treatise on the Etruscans compiled by Thomas Dempster from Scotland was going to be published by the visiting grand tourist Thomas Coke, Earl of Leicester, with the support of Filippo Buonarroti, a descendant of the great Michelangelo.

Fig. 2 The Minerva of Arezzo, Etruscan bronze, ca 300 BCE, discovered in 1542 and displayed in Palazzo Ducale (Palazzo Vecchio), then in the Uffizi Gallery (Museo Archaeologico inv. n. 3)

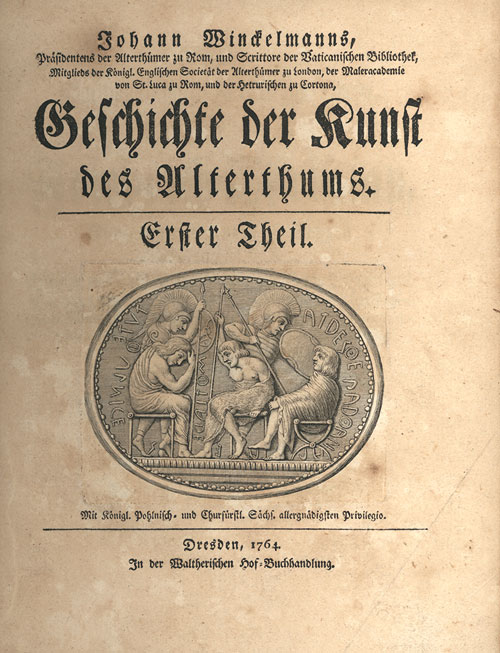

Therefore, three hundred years after Winckelmann’s birth, the Archaeological Museum of Florence recently inaugurated an exhibition that examines the impact of the Etruscan tradition on the German antiquarian and art historian who was going to return to this subject matter more than once and even dedicated an entire chapter to it in his History of Ancient Art. Winckelmann had come to Florence to catalogue the collection of cut stones amassed by the late Baron Philipp von Stosch. Through this occupation and through the contacts he was able to make with the learned antiquarian circles of Florence he was able to study Etruscan art in the context of a typical Florentine “Etruscheria” and in exchange with an international cast of scholars and connoisseurs. In this post-Medici Florence in which the house of Habsburg-Lorraine was now in charge, ideas of the enlightenment were gradually taking hold. The city had long become the goal of grand tourists from all over Europe. The first consulates were being established in Tuscany and the British diplomat Horace Mann (1706-1786) used his position to attract the services of artists such as Thomas Patch (1725-1782) and to deal in works of art as a side-line to his day job. Johann Zoffany (1733-1810), for example, would be commissioned to portray the Uffizi Tribuna for the British Crown in 1772-1778 (Royal Collection). Winckelmann’s Geschichte der Kunst 1764 (Fig. 3) is still a seminal text for understanding Classical Reception in the eighteenth century.

Fig. 3 Front cover of Johann Winckelmann’s Geschichte der Kunst, Dresden, 1764

The 100-plus objects on view in the Salone del Nichio of the Archaeological Museum bring Winckelmann’s visit to Florence into focus. Among these are on show some of the major Etruscan works of art gathered in the Florentine collections long before the arrival of the German antiquarian, such as the famous Chimaera, the already mentioned Minerva or the so-called “Idolino from Pesaro”. Other exhibits are closer to Winckelmann’s own activities in Florence, such as a complete set of plaster cast copies of the “Gemme Stosch” from Stendal, his manuscript notebook (“taccuino fiorentino”, Accademia di Scienze e Lettere “La Colombaria”, inv. n. IV. II. II. 52), which is preserved in Florence and was published in 1994, and the first complete edition of Winckelmann’s works published in Prato between 1830 and 1834.

The exhibition thus brings together a rich array of Etruscan masterworks from the Medici and other Florentine collections, manuscripts and rare books, portraits and curiosa related to the scholarly and artistic engagement with the Etruscan culture in the long eighteenth century. The catalogue, composed by Italian and German Etruscologists and specialists on J. J. Winckelmann, provides much-needed context regarding a period in Florentine history that was marked by political change, societal and scholarly progress and a great international exchange as part of the effects of the Grand Tour. In the case of Winckelmann’s visit to Florence, this context affected his antiquarian work and finally brought the Etruscans very much to the attention of the cognoscenti.