by Andrea M. Gáldy, with Stefanie Fricke, Sabrina Kessler, Felicitas Meifert-Menhard

War and Peace

Bayerische Landesausstellung 2015 Napoleon und Bayern” Ingolstadt Neues Schloss, Bayerisches Armeemuseum, Paradeplatz 4, 85049 Ingolstadt [Bavaria,Germany]

30 April to 31. October 2015, every day 9.00 am to 6.00 pm

Organisers: Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte (www.hdbg.de/napoleon/), Bayerisches Armeemuseum (http://www.armeemuseum.de/de/ausstellungen/sonderausstellungen/62-ausstellungen/sonderausstellungen/beschreibung-sonderausstellung/707-2015-napoleon-ausfuehrlich.html) and the city of Ingolstadt

Andrea M. Gáldy

War has been represented in art, literature and film. It has been the subject matter of exhibitions and museums, often glorifying victory and in recent times more frequently warning against the inherent dangers. The question Does War Belong in Museums? was asked in the title of at least one publication (ed. Wolfgang Muchitsch. Edition Museumsakademie Joanneum I. 4. Bielefeld: transcript, 2013) and can probably not be answered satisfactorily to cover every kind of museum worldwide. While the traditional army museums still exists, many such institutions currently undergo radical changes. Nonetheless, key anniversaries continue to be remembered by special exhibitions and conferences.

In the English-speaking world, Napoleon Bonaparte achieved cult status as a kind of archenemy and anti-Christ. It took the combined efforts of military heroes such as Nelson and Wellington to beat him and his armies. Even though the epic battles of Trafalgar and Waterloo may no longer hold the same pride of place in the British public conscience as they did 50 or 100 years ago, the names still grace major squares and train stations. The house a grateful nation gave to the Duke of Wellington has been a shrine to his as well as to Napoleon’s memory since 1853, when a “Museum Room” at Apsley House was opened to the public. In 1943 the house and much of its contents were offered to the Nation by the 7th Duke of Wellington. In the long run, fighting Napoleon even helped to shape the British Nation within the not always so United Kingdom. Nowadays, under the influence of the special relationship to the US and as a not always very happy part of the EU, this idea of nation is changing rapidly as the recent elections and a conference, entitled “Quo vadis, Great Britain?” held at Munich this September have been able to show (see the added conference report below).

While in Britain, Napoleon is considered a military opponent not to be underestimated but definitely not to be admired, in continental Europe, where most of his campaigns took place and had a direct impact on civilians as much as on military personnel, the attitude is more diverse. In German, the Napoleonic Wars are usually referred to as “Befreiungskriege” [Wars of Liberation] and at least for the aristocratic members of the Ancien Régime the final defeat of Napoleon will have been an act of liberation. Nonetheless, the population of the many German states who bore the brunt of the horrors of war also had reason to be grateful to the Revolutionary and later Napoleonic French influence, which had a thoroughly modernising effect on the society, education and the legal system to name but a few examples.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the former Duchy of Bavaria had become an electorate with royal ambitions. Part of the Holy Roman Empire it was tied to Austria, which was at war against France and needed allied troops. So far, the relationship had not been good: Bavaria feared to be overrun und taken over by Emperor Franz II. Bavaria under Max IV. Joseph decided to change sides after the French victory at Austerlitz in December 1805 and finally ratified the treaty of Bogenhausen. In January 1806, Bavaria became an independent kingdom obliged to provide military support to Napoleon’s Grande Armee. From now on Bavarian soldiers died for the French emperor on many battlefields, they saw military action in Russia and retreated before the Russian winter in the hope to reach home alive.

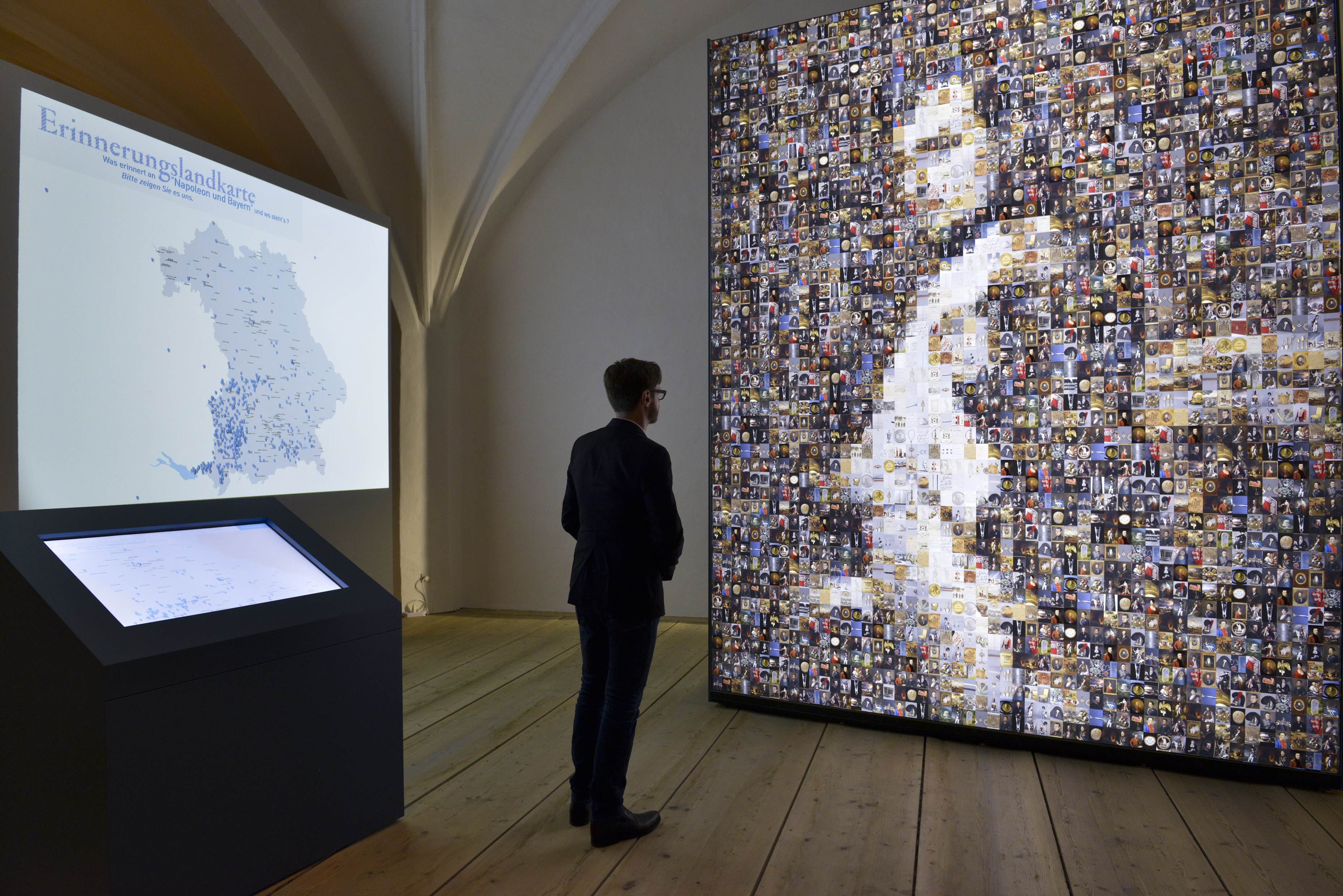

The Ingolstadt exhibition takes the encounter between Napoleon and Bavaria of October 1805 as its point of departure, when the French emperor entered Munich in a festive entry (Fig. 1), which was depicted by Nicholas-Antoine Taunay for the Tuileries in 1808. At the moment of this festive and perhaps even joyous entry, few will have foreseen the future difficulties and the uneasy relationship to come. Apart from providing troops and supplies, Bavaria had to pay a heavy price for its rise in rank. On the one hand, the daughter of King Max I Joseph had to marry Napoleon’s stepson Eugene Beauharnais to confirm the treaty. On the other, theft, looting and rape by alternating Austrian and French Armies were a constant in the lives of the population.

Although elements of traditional exhibitions are represented in the form of paintings, clothing and accessories, jewellery, weapons (Fig. 2) and scientific instruments, these are displayed in a form that gives maximum impact on the importance they had two centuries ago to the lives of their former owners. The Bavarian king’s earrings, which he wore as a former military man, pieces of furniture, crockery and the queen’s competition with the fashion icon Josephine (Fig. 3) give a flavour of nineteenth-century high-society and the changing taste towards a refined empire style in Bavaria. Dashing uniforms (Fig. 4) as well as the simple gear of common soldiers attest to the hierarchy in society as well as on the battlefield, even though it was at least in theory possible to rise through the ranks by an astonishing act of bravery.

The audience is drawn into the exhibition narrative at all levels, not least by the videos and soundbites, which use contemporary paintings and drawings executed on campaign as well as extracts from original letters. They clearly show the suffering of officers as well as of soldiers stranded in a hostile and bitter cold country without food or adequate clothing. The horses and other animals accompanying the army fared particularly badly and also died in great numbers. Much of the space in the exhibition is – rightly – given over to the horrors and the loss of lives on campaign and at home.

Crown Princess Amalia Augusta’s husband Eugene witnessed the Russian campaign and Moscow burning. He made it back safely to Bavaria and continued to live there with his wife even after his stepfather’s fall and his final defeat at Waterloo. Perhaps what he had seen in the field and in the private lives of the leading families, often little more than pawns in the game of high politics, had taken away any appetite he may once have harboured for a role at the top. Others, however, developed an ever greater appetite for power. One display, which discusses the Congress of Vienna, shows a table laid as if for a banquet. Each place is set for a different country that attended the congress and hoped to gain greater wealth and influence in Europe. The continent itself is symbolised by a plate of cakes about to be distributed among the victorious. The scene also illustrates the saying that you cannot have your cake and eat it too.

Bayern, 1813 –1820 (Bayerisches Armeemuseum, Ingolstadt © Bayerisches Armeemuseum/Christian Stoye, Ingolstadt)

For Bavaria, the encounter with Napoleon, the treaty and military alliance, proved beneficial in the long run. Despite the many sacrifices made by all ranks of society up to 1815, Bavaria came out of the Napoleonic Wars as an independent kingdom with a modern constitution. The citizens lived in a modern state, which offered some religious tolerance, a reformed educational system, insurance societies and the security of legislation. Such achievements might have been reached without Napoleon eventually as well, though it would most likely have taken much longer if Max IV Joseph had not seen the chance to fulfil his royal ambitions.

(Note: all images have been put at our disposal by the Bayerisches Landesmuseum)

Review

“Quo Vadis Great Britain?”: ‘Britishness’ in the Year of the Waterloo Bicentennial

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich

Department of English, 14.09.2015 – 16.09.2015

As scholars of the humanities are very aware, the past is not just the past, but history is always fashioned, ‘emplotted’ to structure contingent events into a coherent narrative and to make them meaningful for the present. History especially serves in the creation of larger communities, which, according to Benedict Anderson, are always imagined and have to define themselves via a shared language, traditions, and a common history. Embedding certain historical events, heroes and villains in the collective memory, and remembering them again and again, helps to stabilize nations, to give answers to questions about their origins and their specific characteristics, and to distinguish them from other nations.

2015 saw the anniversaries of two key events for English and British history and identity: In 1215 King John I negotiated a charter with his barons which became known as Magna Carta. And in 1815 the Duke of Wellington ended the long wars against France by defeating Napoleon at Waterloo.

Based on these events and their commemoration, the interdisciplinary conference “Quo Vadis Great Britain?”: ‘Britishness’ in the Year of the Waterloo Bicentennial raised the question what role the past still plays in modern Britain. Since Waterloo, British society has changed dramatically. It is now multicultural and no longer united by Protestantism or enmity against the hostile Catholic Other France. What does it mean to be British today? Why is there such a yearning for the past, fuelling an ever growing heritage industry? Why are British cultural products so popular worldwide and what do they tell us about British society? And how does Britain deal with its role in Europe and the world, as well as with separational developments within the UK?

At the start of the conference, William Gatward of the British Embassy in Berlin gave an interesting keynote on Britain’s role – and its self-conception – in our world today. In the following, scholars from different backgrounds (including literary scholars, sociologists, film theorists) presented a great variety of papers related to the conference’s topic, focusing for example on ‘Waterloo architecture’, expressions of modern imperialist politics in James Bond, the political effects of the 2015 General Election, the role of the monarchy and the Queen, differences in 18th-century marriage-law between England and Scotland, poetic contributions to the Scottish Referendum of 2014, utopianism in modern literature, and British identity as reflected in cultural products such as Doctor Who, the Hammer films and Fawlty Towers (see the website http://www.anglistik.uni-muenchen.de/aktuelles-vortraege/quo-vadis-great-britain__/index.html for the whole programme).

The wide range of topics addressed, as well as the lively discussions, attested to the topicality of the conference’s subject and showed that even in modern, multi-cultural Britain, the past is still very much alive.

Stefanie Fricke

Sabrina Kessler

Felicitas Meifert-Menhard