By Jack Martinez –

War! What is it Good For? Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots

Ian Morris

Farrar, Straus and Giroux (April 15, 2014)

512 pages

In his recent book, War! What is it Good For?, Ian Morris writes, “War has made the planet peaceful and prosperous.” Since its release, the book has attracted a fair amount of attention for arguing the “positive side” of war. It’s easy to see how this sort of claim could inspire backlash, but the book goes so much deeper than what its tagline suggests.

I once dipped my toes into the world of military history when I travelled to the Alps with some Stanford archaeologists studying Hannibal’s invasion. Setting foot on the sites of famous campaigns illustrated to me the intersection of the material sciences and history. As authors like Morris and his contemporary Jared Diamond have shown, geographic and ecological determinism can be decisive in the rise and fall of societies. An archaeologist and the author of Why The West Rules’For Now, Morris has adapted a range of methods’statistical, geographical, and anthropological’to examine some of the central questions of global history: why is our story defined by violence, what has violent brought us, and where will it lead us?

Morris is the rare academic who can masterfully command the attention of general audiences. As one of his students at Stanford, it’s often funny to see how easily his lecture style translates to the page. The book’s clarity and humor are among its chief strengths. Taking his title (with characteristic irony) from the 1970 Edwin Starr protest song, Morris argues that over the long run, war has played a central role in making humanity “safer and richer.”

Such an idea can’t be devoid of controversy. But the many intellectual gifts of this book are not only found in its central conclusion; Morris’s near-Herodotean powers as a storyteller make the pathway to his thesis worthwhile even for the fixedly pacifist student of history. The benefit of his archaeological approach is its combination of the personal and the objective. In the course of a few pages, Morris is able to move us from a chart showing millennia of data on social development to an in depth description of inscribed Sumerian stela.

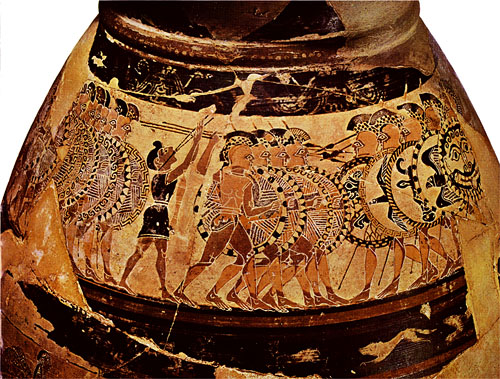

The bulk of the text focuses on major developments in technology and tactics, particularly in Europe; probably the most entertaining part of reading this book is lingering for a few pages on subtopics like Bronze Age chariot warfare. Military buffs will enjoy touring through the technological revolutions, including the development of metal weapons and organized standing armies.

Ultimately, the claim that war ultimately improves the world rests on how well one receives a statistical approach to human history. Similar to Why the West Rules, the timeframe of War! stretches from Classical antiquity to the present day. Though the two books often parallel each other, most of the content of War! won’t be redundant for fans of Morris’s previous work. The book paints history as a story of large governments swallowing up smaller, more chaotic societies. Conquerors from the Roman Empire to the Allies of World War II are depicted as reigning in aggressor states and tribes. Morris believes that this process favors the majority of people; governments that fail to create peace for their subjects are overthrown or internally weakened, leaving them open to defeat by more benign powers.

One of the book’s more interesting digressions details violent chimpanzee behavior. Evolutionary evidence extending back to primates suggests that humans are predisposed to violence if left in a Hobbesian “state of nature.” This aspect of our nature, to Morris, explains why the feudal states of the first millennium created quotidian terror for common people’national powers did not enforce the rule of law over marauding lords acting like competing chimp alpha males. The problem of a state like Hitler’s Germany, in this view, is actually a story about the triumph of a peaceful “Leviathan” (the Allies) over a smaller, more damaging Leviathan.

The “Hitler problem,” as Morris refers to it, is one of the main challenges of interpreting this book; the reader is asked to look at the atrocities of the World Wars almost as aberrations in the grand scheme of things. Some early reviews of the book (notably, in The Guardian) resisted the idea that war can be proven “good” on statistical grounds. It’s certainly challenging to accept that the 20th century has been the most peaceful period of history. World War I challenged authors like Hemingway and C. S. Lewis, who experienced and documented the horrors of trench warfare and mechanized battle. In Lewis’s case, the experience of war was extreme enough to jade him spiritually and turn him into an atheist before his eventual turn to Christianity. Statistical analysis proving that Western Europe has been safer and richer in the twentieth century – compared to its previous history – can’t dispel the fact that war is hell.

Nor does Morris expect it to. His approach rests on a somewhat dim view of human nature, closely paralleling Hobbes. Evidence of extreme violence rates from the archaeological record lead him to suggest that life in most ancient societies truly was nasty, brutish, and short. In our hyper-literate, information rich age, academics and lay readers alike can consume media and texts that illustrate the horrors of contemporary violence. In contrast, our knowledge of Stone Age societies (and even more familiar ancient societies like Rome) is extremely limited by the surviving evidence. It is hard to know just how much killing took place “between the battles” in prehistory and early recorded history. Evidence from archaeology may suggest that warring Leviathans don’t pose nearly as much of a threat to the individual person as the near-anarchy of decentralized societies.

The end of the book extrapolates Morris’s ideas into predictions for the future. Along the way, the book dips into contemporary conflicts, especially America’s use of force to “preserve global order” in the Middle East. More than the rest of the book, readers’ reception of these ideas will depend on their politics.

One core suggestion is that advancing technology will eventually put war between humans “out of business”‘if, that is, we can ward off a major superpower conflict long enough. Borrowing some terminology from science fiction, Morris imagines that humanity will evolve into a different sort of animal, with a closer relationship to technology and information.

The intersection of military technology with the civilian world is a phenomenon that will need to be treated more extensively to incorporate current events. Military projects like DARPA (an agency of the Defense Department) have, historically, had unexpected contributions to civilian technology’beyond giving us things like duck (duct) tape, microwaves, and cargo pants. Increasingly, through drone warfare and cyber warfare, the worlds of conquest and computing are merging. The current drone controversy proves that this is going to matter for citizens, not just policymakers.

The ambition of War! should serve to inspire the student of history as well as general readers. It is rare and satisfying to see such a well-wrought blend of past and present, particularly with a comparative global approach. Any “big picture” study that uses archaeology is welcome in a discipline often defined by minutiae. The methods of Morris’s study alert us to the possibilities gleaned in blending the quantitative and the literary, the material and the human, science and history.