By Leah Mordehai –

“A single Voltaire will do more honor to France than a thousand pedants, a thousand false wits, a thousand great men of inferior order.” Frederick the Great

Why was Frederick II of Prussia an enlightened ruler?

One of the most enlightened rulers of all time, Frederick II the Great (1740-86) of Prussia exemplified the ideals of the Enlightenment. As King of Prussia, he expanded Prussia’s territory through a series of wars, most notably the Silesian Wars, which solidified Prussia as a major European power. His military prowess was showcased during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), where he successfully defended Prussia against a coalition of Austria, Russia, France, and Sweden, despite being vastly outnumbered. Through his military and administrative reforms but also in his patronage of intellectual and artistic movements, Frederick was more instrumental in modernizing 18th century Germany than any other figure of his time in Europe.

Few kings or rulers in history have earned the description of being enlightened. Cyrus as king of Achaemenid Persia in the 6th century BCE deserves this epithet for abolishing some forms of conquest slavery and returning deported peoples back to their homeland, even at times with remuneration for their lost treasures or precious religious relics if ancient textual history is accurate. The second century CE Roman Emperor Trajan could be considered enlightened for his renowned justice at the height of the Roman Empire when Rome was at its greatest. King Alfred of the Anglo-Saxons (849-99 CE) and Charlemagne (748-814 CE) can also be considered enlightened for their early medieval lawgiving and administrative wisdom that resulted in economic growth shared with their peoples.The Medieval king Federico II (1194-1250 CE) known as Stupor Mundi “Wonder of the World” in Norman Sicily could also be noted for his inclusivity and political ability to avoid religious war even in his 13th c. Crusade demanded by the Church which he did in returning Jerusalem to Christianity without shedding any Saracen blood. There are other rulers who could be mentioned but any of these – even if all of them were imperfect – suffice to compare to Frederick II of Prussia for some form of enlightened intellectual and political genius in his rulership.

Frederick II was not only a brilliant military leader and statesman – he maintained that the ruler should be first the servant of his people and not vice versa – but was also much connected to the profound thinkers of his day like Voltaire, with whom he also had a long correspondence. Frederick was also an accomplished musician and composer since his youth and invited Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), whom he greatly admired, to Potsdam where he gave him a theme on which to write contrapuntal variations. Last but not least, he was very progressive about the rights of people including gender equality and even a benevolent friend protecting the rights of repressed people, including women and those of homosexual directions, unlike so many of his contemporaries, offering legal protection. Frederick, fluent in French as well as German, also introduced legislation that allowed freedom of the press and while he was a religious skeptic, he brought greater religious tolerance for both Roman Catholics and Jews – although he was not always consistent in his toleration – where what became Prussia had been a Lutheran state for centuries. In almost every endeavor, Frederick was thus very much the paragon of the Enlightenment.

Frederick and Voltaire

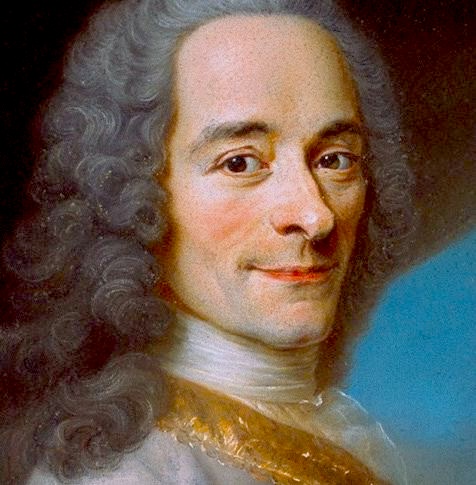

Frederick shared a noteworthy correspondence with the French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778), an Enlightenment pioneer, marking a relationship that spanned decades. Through their letters, the two men exchanged ideas on governance, philosophy, and the Enlightenment. Voltaire, a champion of reason and individual freedoms, influenced Frederick’s views on religious tolerance and legal reform. Voltaire’s correspondence with Frederick began in 1736 and he became a guest of Frederick at Potsdam on multiple occasions, partly because the two were both deep thinkers and geniuses critical of much of European life and monarchy. They shared not only religious skepticism but also their philosophies and broad-ranging appreciation of literature and history had many mutual intersections, as Davidson elaborates. There is little question whether Frederick had read Plato’s Republic and knew about the ideal philosopher king whom he seems to have emulated wherever possible in his own way.

M. Q. de la Tour, portrait of Voltaire (image public domain)

Because Frederick was both a Francophile and fluent in French, he was in the vanguard of most of the Enlightenment movement coming out of France. While he wasn’t a fan of the universal Encyclopédie (Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers), he provided protection to the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau during difficult times. His amicable intellectual relationship with Voltaire lasted through the majority of both their lives.

Frederick and J. S. Bach

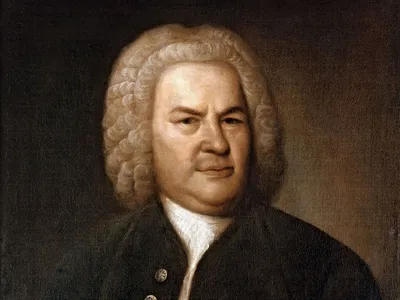

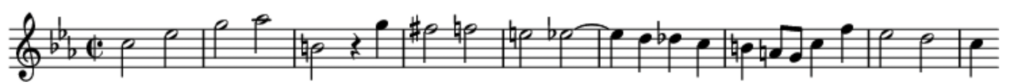

Frederick the Great’s interaction with Johann Sebastian Bach in 1747 remains one of the most iconic moments in music history. Because Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emmanuel was a court musician for Frederick, the king invited Bach to his court in Potsdam, possibly laying a musical trap for Bach to test his musical proficiency. Knowing Bach’s reputation for brilliant improvisation, Frederick, an accomplished flautist, challenged the composer to improvise a fugue on a difficult C minor RICERCAR theme he provided. Bach, initially struggling with the highly chromatic theme, quickly transformed it into a magnificent six-voice fugue, impressing both the king and the court. In response, Bach composed Das Musikalisches Opfer (The Musical Offering BWV 1079) in C minor, dedicating it to Frederick. The work explores the theme through intricate fugues and canons, showcasing Bach’s virtuosity and his respect for the intellectual challenge posed by the king. Bach also taught Latin at the St. Thomaskircheschule in Leipzig, so he made a steganographic (“hidden in plain sight”) and acrostic Latin word play on the title RICERCAR using R.I.C.E.R.C.A.R. (Regis Iussu Cantio Et Reliqua Canonica Arte Resoluta, “Theme given by the king resolved in canonic art”). The trio sonata, part of the response offering, may have also been a playful challenge to Frederick, featuring a notoriously difficult flute part. This exchange exemplifies the blending of intellectual and artistic pursuits in Frederick’s court.

As a musician, Frederick was not only a virtuoso traverso flautist since youth, he was also a respected composer himself, composing over 120 sonatas and a number of instrumental concerti, sinfonias, marches and arias and even wrote libretti for opera. Notably, he advocated for Prussian opera to be free for all to attend.

J. S. Bach by E. G. Haussmann, 1746 (image public domain)

Frederick’s RICERCAR theme for Bach

Bach playing The Musical Offering from Frederick’s theme, Potsdam, 1747 (image public domain)

Frederick continued to patronize music throughout his reign, subsidizing other composers such as Carl Heinrich Graun, Franz Benda and Johann Quantz, with most of whom he collaborated musically.

Prussian Legal and Social Reforms under Frederick

Germany’s legal history is a tale of transformation—one that begins under monarchies and authoritarian rule before shifting toward a progressive framework for human rights and gender equality. Frederick had studied Machiavelli closely and wrote a rebuttal to Machiavellian pragmatic cynicism in his Anti-Machiavel (1740) written in French along with his later Testament Pollitique. In his administrative genius, Frederick introduced indirect taxation, fire insurance, reformed the Prussian civil service bureaucracy, reinstituted the Prussian Academy of Science and founded a credit bank for stabilizing what had been a volatile economy. He also reformed the Prussian judiciary, making advancement based more on merit than class and openly promoted freedom of the press and freedom of literature without censorship as well as providing a much broader legal egalitarianism for all Prussians. He was also instrumental in removing the death penalty for all but the most heinous of crimes. Another of his lasting accomplishments was advocating for a more diverse immigration to bring gifted outsiders to Prussia. While no fan of sport hunting in what he perceived as a cruel pastime, Frederick’s agricultural policies also mostly promoted better land use and made the potato a German staple.

While Frederick is probably most often remembered for his military brilliance – not a topic here since it is covered elsewhere in depth – and his Enlightenment Era reforms, his personal life remains a subject of deep historical debate. The evolution of gender rights in Germany is as much about legal reform as it is about the individuals who challenged societal norms. From the reign of Frederick the Great in the 18th century to modern legislative strides in gender and LGBTQ+ rights, Germany has played a pivotal role in redefining legal and social understandings of identity. Many historians now believe that Frederick was likely gay, an aspect of his identity that shaped both his personal relationships and his approach to governance.

From an early age, Frederick struggled against the rigid expectations of Prussian masculinity imposed by his father, King Frederick William I. While his father valued militarism and discipline, Frederick was more drawn to philosophy, the arts, and music. This tension culminated in a dramatic and tragic event in 1730 when Frederick and his close friend, Hans Hermann von Katte, attempted to flee Prussia. The attempt was seen as both an act of treason and a rejection of Frederick’s arranged marriage to Princess Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, which he despised. His father, outraged, had Katte executed before Frederick’s eyes—a traumatic experience that shaped his detachment from romantic relationships with women for the rest of his life.

Despite eventually marrying Elisabeth Christine, Frederick openly disregarded his wife, leaving her to live in a separate palace and refusing to engage with her beyond formal duties. His letters and personal writings suggest a lack of interest in women and an intense preference for the company of men. He maintained deep relationships with male companions, including Voltaire and other Enlightenment thinkers. His interactions with men, particularly those he favored at court, suggest he formed intimate, possibly romantic bonds.

There have been several accounts of Frederick the Great’s relationships with men. French diplomat Dieudonné Thiébault, who spent time at Frederick’s court, remarked on the king’s exclusive preference for male company and his disinterest in women. Other contemporaries hinted at Frederick’s close, and potentially romantic, relationships with young officers and intellectuals. Unfortunately, no explicit confirmation exists due to 18th-century social norms and the destruction of personal correspondence after his death.

Frederick’s personal experiences likely influenced his more progressive stance on gender and social roles. His Enlightenment-driven policies sought to modernize Prussia, moving away from rigid feudal traditions and reinforcing the idea of the state as a rational, well-ordered entity. Although he did not directly challenge heteronormative structures, his rule saw significant legal reforms that expanded the rights of women and minimized gender-based legal distinctions, reflecting the broader Enlightenment emphasis on reason and merit over inherited privilege.

One of Frederick’s most notable contributions was his use of gender-neutral language in legal documents, a practice highly unusual in 18th-century Europe, where laws overwhelmingly favored men. This linguistic shift aligned with his vision of a centralized, efficient government in which laws applied universally rather than reinforcing rigid social hierarchies. While this was not necessarily a conscious move toward gender inclusivity as understood today, it demonstrated his commitment to legal rationalization over feudal customs that had long subordinated women.

Frederick also championed educational reforms that granted greater access to learning for women, a move that subtly challenged traditional gender roles. Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire and Christian Wolff, he promoted a more secular, knowledge-driven society, which in turn encouraged the participation of women in intellectual life. His patronage of female scholars, such as Emilie du Châtelet, reflected his belief in intellectual merit over gender restrictions. Additionally, the expansion of Prussia’s school system under his reign, while primarily focused on training boys for military and civil service, also allowed greater educational opportunities for middle-class girls.

While Frederick the Great is often remembered for his military conquests and legal reforms, one of his most quietly brilliant achievements was convincing a skeptical nation to eat potatoes. In the face of looming famine, Frederick saw the newly introduced potato as a practical, nutritious solution. However, despite royal edicts encouraging its adoption, the general population resisted. In the words of a contemporary Prussian saying, “Was der Bauer nicht kennt, frisst er nicht” (“What the peasant doesn’t know, he won’t eat”). Rather than mandate its cultivation through force, Frederick turned to psychology. He ordered potato fields to be planted near Berlin, had them guarded by soldiers—and then cleverly instructed the guards to look the other way. By making the potatoes appear valuable and restricted, he sparked public curiosity and desire. Before long, peasants were “stealing” the royal crop and growing it themselves.

Prussia continued to show early signs of gender diversity recognition in the 19th century, as certain cases emerged where individuals who did not conform to traditional gender identities received some form of legal acknowledgment. Though these cases were rare and not indicative of widespread acceptance, they were notable given the rigid gender norms of the time where previously only two genders were accepted, whereas the enlightened Frederick allowed more gender fluidity.

Germany’s legal evolution continued into the modern era. In 1969, the country decriminalized homosexuality, marking a turning point in its approach to LGBTQ+ rights. In 2017, same-sex marriage was officially legalized, further solidifying Germany’s commitment to equality.

One of the most groundbreaking legal advancements came in 2018, when Germany became one of the first nations to legally recognize a third gender option on official documents. This decision can be seen as an extension of earlier legal traditions in Prussia that, centuries ago, had already begun to question strict gender classifications.

Frederick’s legacy, complex as it may be, reveals that even in an era of rigid gender expectations, there were those who lived outside the boundaries of traditional norms. His rule, shaped in part by his genius across a range of contributions in philosophy, music, military science and the arts as well as a frank questioning of his own sexuality, left a lasting imprint on German cultural and legal traditions, paving the way for the future in what would become a progressive state in different centuries. While such progress is often stymied by successive generations – including a temporary benighted phase in Germany in the second quarter of the 20th century – nonetheless Frederick’s own intellectual brilliance, tolerance and broad contributions have left a lasting legacy beyond his Prussian state into modern Germany of the 21st century. If ever there was a philosopher king in Plato’s mold, it was likely that Frederick came close to the ideal.

Sources:

Aramayo, Roberto R. The Chimera of the Philosopher King…Madrid, Ediciones Alamanda, 2019.

Ashton, Bodie A. ‘Kingship, Sexuality and Courtly Masculinity: Frederick the Great and Prussia on the Cusp of Modernity.’ In ANU Historical Journal Vol II. Iss 1, (Australian National University 2019).

Blanning, T. W. C. Frederick the Great, King of Prussia. Random House, 2016.

Boyd, Malcom. Bach: The Master Musicians. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Davidson, Ian. Voltaire: A Life. Pegasus Books, 2012.

Gaines, James R. Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment. Harper Perennial, 2006.

Hunt, Patrick. “J. S. Bach and Steganography.” Electrum Magazine, Dec. 2013 (https://www.electrummagazine.com/2013/12/j-s-bach-and-steganography/). Also a chapter in a forthcoming music history book from Stone Tower Books, 2025.

Lifshitz, Avi. Frederick the Great’s Philosophical Writings. Princeton University Press, 2021.

MacDonogh, Giles. Frederick the Great: A Life in Deed and Letters. St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Melton, James van Horn. The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2001, 145 & ff.