Tamara de Lempincka, Madonna, 1937

By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

Tamara de Lempincka (1894-1980) was a gifted artist and an iconoclast, often considered a founding leader of the Art Deco movement from the 1920’s through the 1930’s. Art Deco was the perfect trope for an artist known for bold color, symmetry and luminosity at times building on illusion and modernist effects. Because her personality and colorful life were so public and and at times controversial, it took decades to get beyond her persona and publicity for her to be fully appreciated until after the 1960’s, partly because Art Deco went out of style and some thought Lempincka was merely a poseur full of artifice. But even as a young artist, she had paintings exhibited in Paris recognizing her unique style, for example in the Salon des indépendents, the Salon d’automne, and the Salon des moins de trente ans all in the 1920’s. She was in the forefront of avant-garde in both her life and art, unconventional like many artists but maintaining a social life that was often perceived as catering to social pressures in public while privately living the way she wanted. If her art also seemed contrived to some, it was often because they were not as sophisticated in seeing the artistic influences she absorbed and alluded in her paintings and other graphic expressions, including Renaissance, Baroque and Romantic artists. Her paintings have a visual element of unnatural perfectionism in depicting flawless skin and eyes that may be one of her outstanding composition components, a feature that could be perceived as unreal by critics but nonetheless demanded great skill to achieve.

I viewed the recent brilliant visionary exhibition of her work in San Francisco’s Fine Arts Museums (De Young Museum Herbst Galleries), which ran from October 2024 to early February 2025 and have selected a few of my favorites from her paintings, briefly discussed here with a rationale for why they struck me with her genius. One often sees Cubistic tendencies in her architectural backgrounds when buildings or other features are rendered, another deliberate result in great contrast to the rounded human figures especially of her women and nudes with their often Mannerist-inspired distortions.

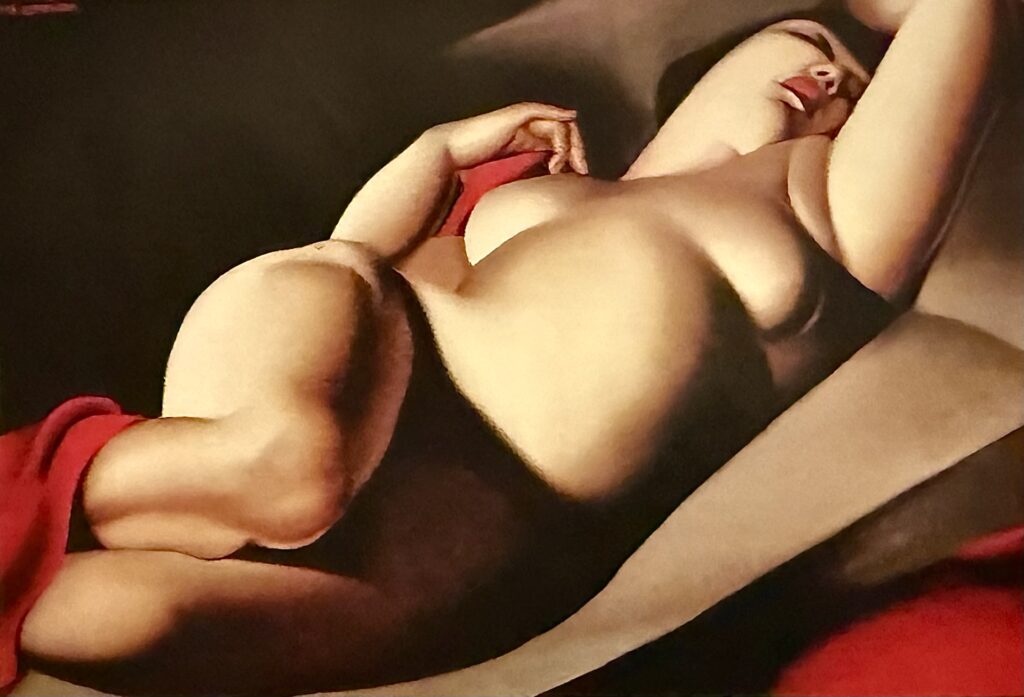

Tamara de Lempincka, La Belle Rafaëlla 1927

Her above nude (La belle Rafaëla 1927 of a prostitute known as Rafaella and with whom she also had a liaison is simultaneously a voluptuous caricature – almost ekphrastic in echoing the influence of Ingres’ Odalisque, not only striking for its fleshy roundedness but also for its dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggiesque light. It is important to remember that when women paint women, we need to suspend some ideas of sexually objectivizing the female body, but in Lempincka’s case it is profound because she was also bisexual and therefore her possible implication of titillatory viewing is also ironic at least.

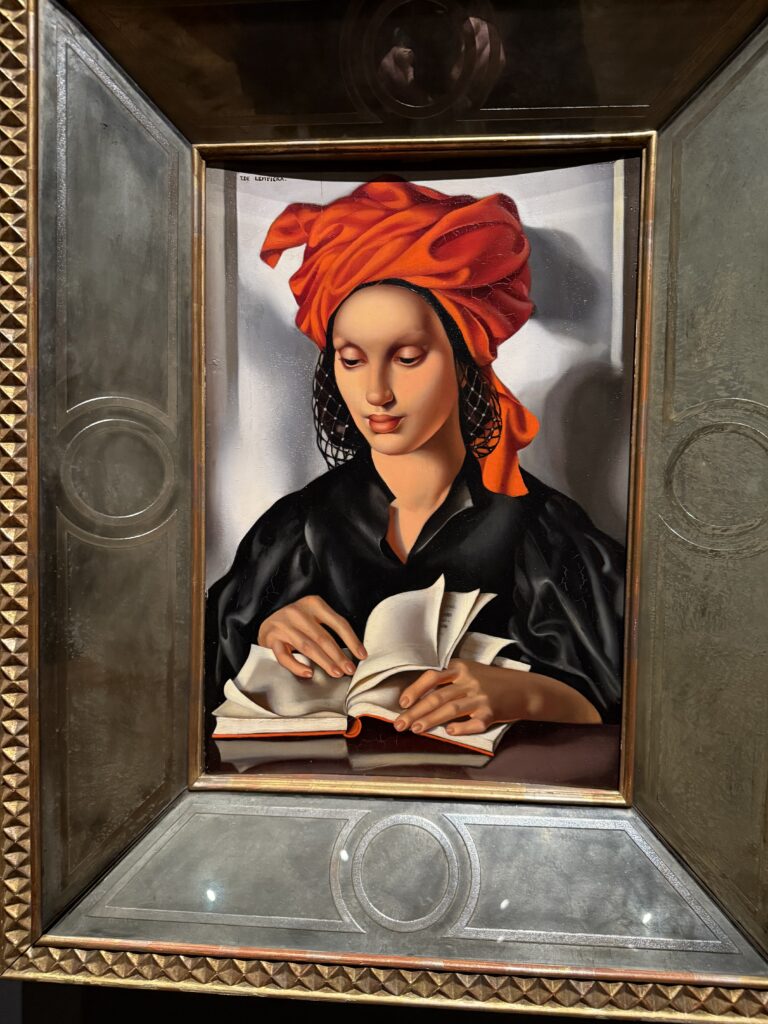

Tamara de Lempincka, La Sagesse, ca. 1940-1

Her above La Sagesse ( “Wisdom” ca. 1940-1) is another “quotation” of a Renaissance style, somehow reminiscent of one of Michelangelo’s prophetic sibyls in the Sistine chapel. Because wisdom is almost always personified as female – like the Hebrew Hokmah or “Wisdom” as her Jewish heritage would have ingrained in her. Michelangelo’s sibyls in the Sistine Chapel may be what the title intimates, and even the red headgear is even much like Micheleangelo’s reds made from cinnabar (mercury sulfide), which is also likely intentional. Her bulging forehead like Zeus pregnant with thought (an Athena foreshadowing in myth) is also a clue to wisdom and mental prowess. These historic clues or trails Lempincka left us appear deliberate but also show off her own idiosyncratic genius as well as her erudition despite the reduction to almost simplicity in composition for which the Art Deco was at times infamous because it wasn’t always seen as serious art.

Tamara de Lempincka, Fruits sur fond noir, 1949

Caravaggio’s natura morta with his early baskets of fruits is clearly alluded in the above still life (Fruits sur fond noir, 1949) which is viewed from a high angle, made even more emphatic by its chiaroscuro background highlighting the pear, lemon and orange. Proof of Caravaggiesque detail is also seen in the grapes, some of which are beyond the “sell-by date” with their age blemishes, just as Caravaggio often painted his fruit with such realism. If we examine some of Caravaggio’s earliest paintings from before 1595 in Rome when he was hired by other artists like Giuseppe Cesari to paint still life, we can clearly see his skill that Lempincka understood and imitated with precision but also added to this legacy with the translucency of her grapes.

Tamara de Lempincka, Madonna, 1937

The lead image – also above – is her Madonna, 1937, which may be a Botticelli imitation, especially because of the blue maphorion of Mary with her white head wimple and tondo form the Renaissance painter also frequently utilized. But it is the depiction of eyes in Lempincka’s repertoire which may arrest the viewer most: they are so luminous especially in their irises which appear almost backlit or to glow with light. This painting is also a masterful study in how multiple textile folds catch or hide light with a range of many hues from blue to white to gray ranges.

Tamara de Lempincka, Bacchante, ca. 1932

Last but not least, her Bacchante ca. 1932 – also known as Eclat or “Brilliance” – with copper ribbons almost substituting for hair and the glabrous green grapes almost as translucent as her eyes is made even more maenadic by the wild red lips which shout out the sensuality of a Dionysian revel, even though this painting is as much an authentic image of reflection as the inspiration of the wine god.

For the briefest of biography, Lempincka was born probably in Warsaw, Poland with a Jewish heritage (her maiden name was apparently Tamara Rosa Hurwitz) but whose family converted at least outwardly to Protestantism. She went to a boarding school in Lausanne for a short time before touring Italy as a teenager with a grandmother. Few rich Polish-Jewish families were as international as hers but as emigres in Paris her family lived off the sales of family jewels for awhile. Lempincka was certainly influenced by Cubism as well as earlier artists like Ingres and Caravaggio, the former for his distortions of figures and the latter for his dramatic light. A student of Maurice Denis and the Cubist artist André Lhote in Paris, she lived almost a century but mostly an emigre, first in St. Petersburg until the Russian Revolution in 1917 then France (1918-39) and ultimately the US (1939-73) and Mexico (1973-80) where she died after seemingly mostly retiring from art for decades. Her Bohemian lifestyle and social prominence – she knew so many important leaders, political and literary figures and hobnobbed with them socially, some of whom she also painted in portraits – fluctuated between aristocratic dalliances and decadent flamboyance, with both marriages to rich male aristocrats, bankers and socialites as well as obvious bisexual and lesbian alliances, including a longterm relationship with the poetess Ira Perrot. These flamboyances and her independence and her frequent flaunting of social norms did not endear her to the keepers of conservative art canons, but perhaps like her Caravaggiesque life were to be expected of a revolutionary.

Clearly her art should be taken seriously, beyond what popular appeal may have diluted in its decades of Art Deco impact and its being much more than what meets the eye. In what was often derogated as deliberated superficiality of her style, Lempincka at times chose to highlight effects at the expense of details. Recent appreciation of her art has led to a revival of her reputation, which now transcends impressions of kitsch temporality and greatly reduces the charge of her art being made only for its time – it will certainly stand the test of the ages for its originality.

In conclusion, her final wish to have her ashes scattered over the active Mexican volcano Popocatépetl (17,694 ft elevation) appears completely sensible because a volcano is perfectly symbolic of her own tempestuous life.