By John Roman –

Historians suggest some religious paintings of the Renaissance may have been intentionally designed to induce subliminal, out-of-body experiences in church patrons.

Michael Kubovy, in his book The Psychology of Perspective and Renaissance Art (1989), uncovered a remarkable twist in artists’ use of perspective during the Renaissance. He explored the idea that the drawing system originally developed to create the illusion of a third dimension on two-dimensional surfaces had also been used by Renaissance painters to subliminally generate spiritual feelings in viewers. Considering the majority of works of art from the 14th-16th centuries were commissioned by the Church, such an intention by artists of that era is not surprising. Kubovy, a specialist in the psychology of perception, explains that the brain is able to perceive the three-dimensionality of a painting even when the viewer’s point of view is off-center from it. This Renaissance tactic seems to have been in wide use during that time, and Kubovy cites the best example of its application as Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

The Center of Projection

Kublovy’s work on this theory was inspired by earlier studies by scholars Carlo Pedretti and Leo Steinberg in the 1970s. All three researchers concluded that Renaissance artists pushed the laws of perspective much further than previously understood. Their studies uncovered the fact that Renaissance artists found a way to relocate what is now referred to as an artwork’s “center of projection.” The center of projection is a focal point within the visual system that does not coincide with either eye, rather, it’s a point between and behind both eyes. (In fact, this localized point is where our eyes and brain actually perceive three-dimensional vision.)

Paintings that use perspective mimic how scenes are viewed through a viewer’s center of projection, with the realism of that painted image best achieved if a viewer aligns their own center of projection with the eye-level and vanishing point in a painting. Where this concept gets interesting is in the suggestion that Renaissance artists understood this, and they devised a way to move a viewer’s center of projection outside the body so the three-dimensional illusion of paintings could be seen even when viewed at skewed horizontal or vertical angles.

Kubovy explains, the brain’s ability to retain the three-dimensionality of perspective is an instinct of the visual system, which is why paintings and drawings always look three-dimensional to us even when viewed at very severe angles away from dead center. When looking at art that is not aligned with our viewpoint, our brain subconsciously assumes an out-of-body location in order to adjust its own center of projection with the center of projection in the artwork being observed.

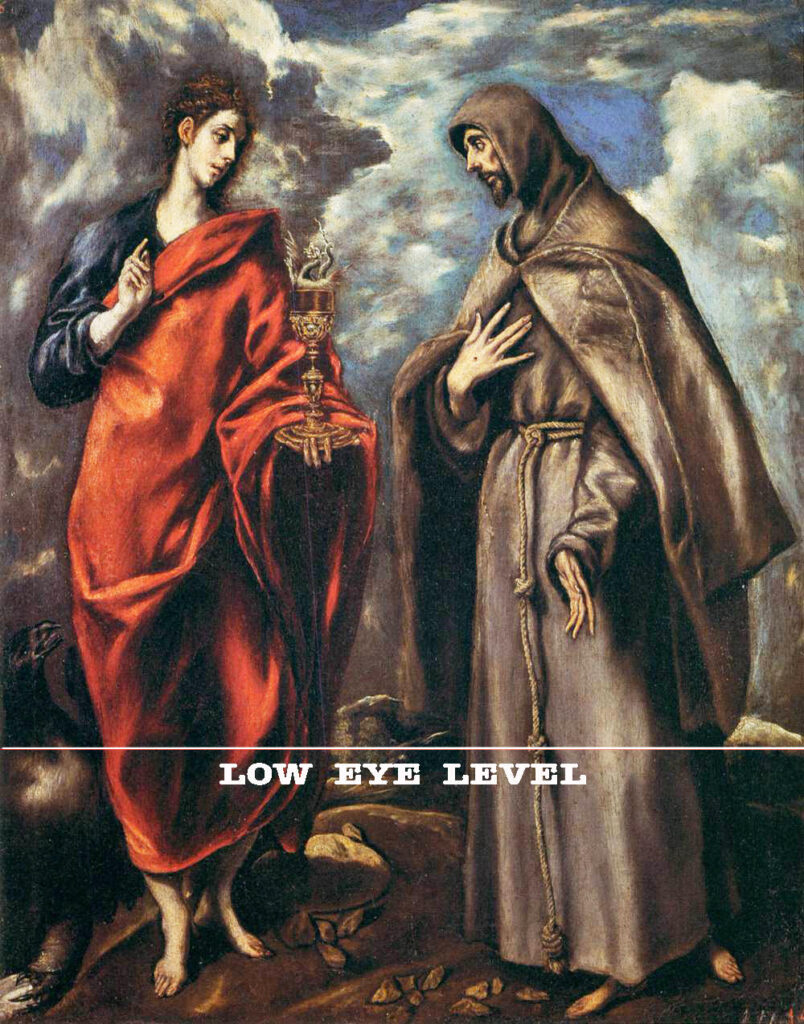

University of Maryland Professor John H. Brown also pointed out in a 2003 essay that a lower placement of the eye level in art works the same way. El Greco’s Saints John the Evangelist and Francis, for example, has a lower eye-level line. With this painting hanging at a normal viewing height, an observer will subconsciously feel humbled, as if they are kneeling before the two saints.

Collection of Uffizi Gallery.

Wikimedia Commons.

Similarly, Andrea Mantegna’s Saint James Led to Execution has an eye-level on the ground where the actors are standing. Again, with the painting hanging at a normal viewing height, this ground-level placement puts the viewer’s center of vision down at a lowly position where we feel we are looking up at Saint James as he is being sentenced to death by his executioners.

The Last Supper

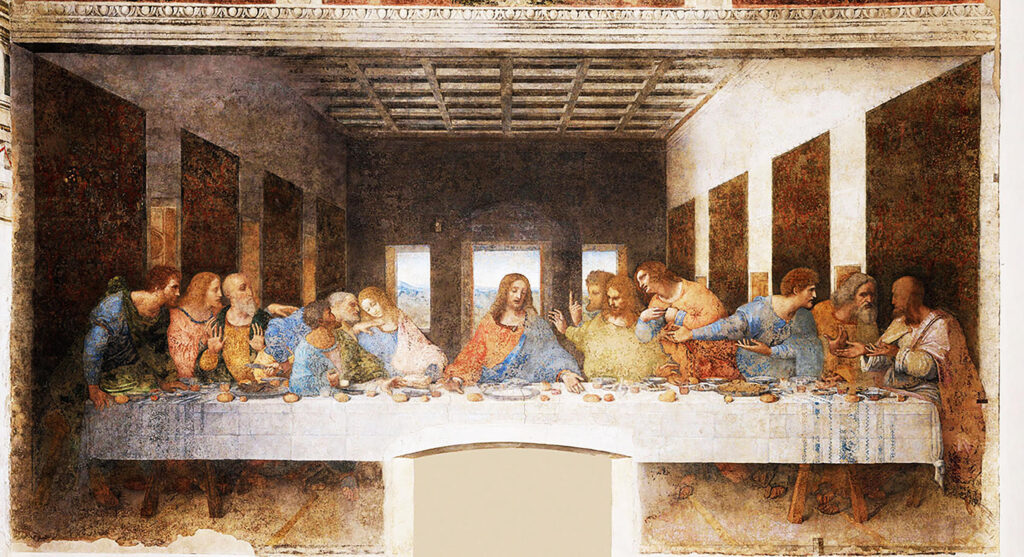

Making his case with a study of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Kubovy begins his analysis with a quote by Leonardo regarding the proper placement of paintings hung on walls. Early in his career, Leonardo made a comment that the center of projection of a spectator and the eye-level in a painting must correspond to each other. He said to disregard this correspondence would make a painting “…look wrong, with every false relation and disagreement of proportion that can be imagined in a work.”

Yet, later in Leonardo’s life, after painting The Last Supper specifically, he violated his own rule by saying, “…a painting, when viewed from below the painting’s eye-level line, will always appear as though seen from above, even though the eye of the observer may be lower than the picture itself.” So, apparently at this point in time, Leonardo claimed that it didn’t really matter if the viewer’s center of projection aligned with the eye-level in a panting. He was now inferring that the mind will automatically correct such visual contradictions.

Painted high on a wall in Milan, Italy’s Santa Maria della Grazie Refectory, the eye-level line in The Last Supper is more than two-and-a-half times higher than an average-sized person. This discrepancy makes it impossible for a spectator on the floor to align their own center of projection with the eye-level in the fresco. Kubovy confirms there have been investigations into the history of the chapel to determine if at any point in its past an observation platform or deck existed to enable visitors to “correctly” view daVinci’s fresco. No such evidence has ever been found.

Kubovy’s research into da Vinci’s strategy is also in agreement with the prior findings of both Pedretti and Steinberg, and is corroborated by Frederick Hartt in his book The History of Italian Renaissance Art (1969). Referring to The Last Supper, Hartt says, “…the represented space in a painting must be an inward extension of the room in which the spectator stands. Although Leonardo’s perspective is consistent, there is no place in the refectory of Santa Maria della Grazie where the spectator can stand to make the picture ‘come right’. Never can the represented walls of the upper chamber [the scene in the fresco] be seen as continuations of the real walls of the refectory.”

It is possible Leonardo came upon this perspective discovery quite by accident and made his contradictory comment after producing The Last Supper. Yet it is also likely that toying with eye-levels in paintings was in use on a wider scale than historians are aware. This optical process may have been applied not only to frescoes, but to the physical hanging of paintings on walls as well.

The Secret Design of The Last Supper

If The Last Supper had been painted the traditional way a mural artist achieves depth in their work, Leonardo would have found a standing position in the refectory from which to view the fresco. He then would have connected all the projecting horizontal lines in his painting to comply with the projecting horizontal lines in the actual room. When a fresco or mural is completed in this manner, the horizontal lines of the real room and the horizontal lines of the fictional room in the painting will all converge to a shared central vanishing point. This practice creates the illusion of one unified space joining both the artwork and the real room.

But when Leonardo, master artist of his time, painted The Last Supper, he disregarded this rule. Instead, he connected the horizontal lines of the fresco and the horizontal lines of the refectory not as one might view the painting from the floor, but as one might view the fresco from an elevated position on the top of a very tall ladder. Only at such a height can the fictional room depicted in The Last Supper produce the illusion of a three-dimensional extension of the actual chapel’s space.

At the core of this theory, all the researchers noted here strongly suspect da Vinci intentionally misaligned those horizontals as a means to employ his hidden agenda for the art. They believe Leonardo’s secret design was meant to separate “…the viewer’s center of projection in relation to the painting and in relation to the room in which they are standing.”

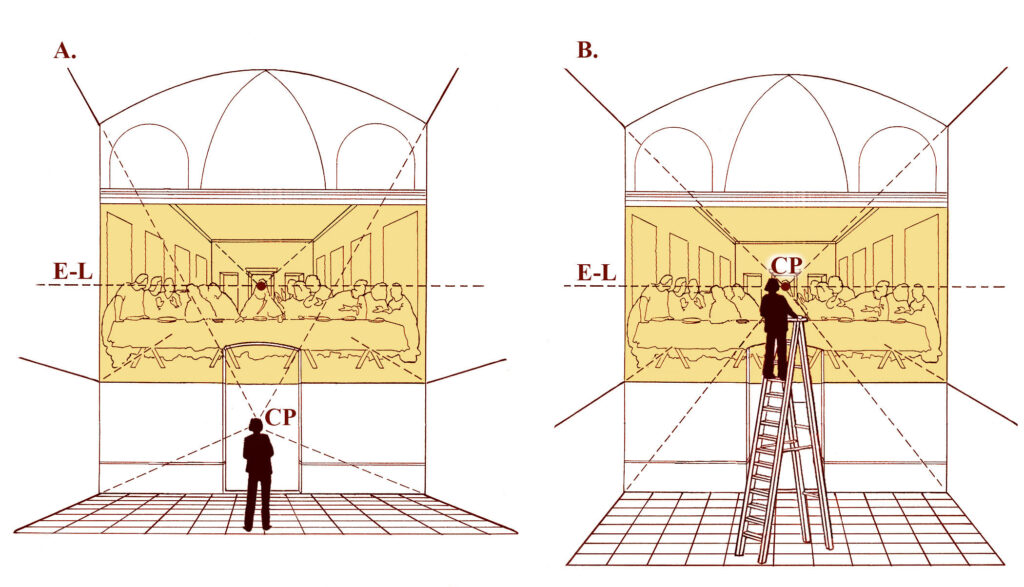

In Figure A, a viewer standing on the floor of the refectory will have a distorted view of The Last Supper. The horizontals of the walls and ceiling in the real room will not merge with the horizontals of the walls and ceiling of the fictional room in the painting. This is due to the difference between the center of projection of the viewer (CP) and the eye-level (E-L) in the painting.

In Figure B the viewer has climbed to a position 4.6 meters (15’-1”) above the floor and is now able to align her own center of projection (CP) with the eye-level (E-L) in the painting. From this elevated vantage point, the horizontals of the walls and ceiling in the real room and the horizontals of the walls and ceiling in the painting properly merge to make the fresco appear as a three-dimensional extension of the actual chapel room.

Note: According to Kubovy’s theory, however, the viewer in Figure A will have her “mind’s eye” subliminally elevated to the correct (out-of-body) viewing height and, therefore, she will also see the fresco in true perspective.

The Powers of Perspective

What better opportunity for an artist to instill a discreet, spiritual response in their audience than with a religious mural? These studies shed light on the fact that artists have been experimenting with perspective in unorthodox ways for centuries, and suggests they realized its variations could have profound effects on perception. More importantly, this evidence points to a subtle intent by Renaissance artists to use perspective in a manner that goes well beyond solely creating the illusion of a third dimension on a two-dimensional surface. Their historic efforts hint at a vigorous attempt by artists to use the powers of perspective as a means to reach deep into, and manipulate, the human mind.

©2024 by John Roman

WORKS CITED

Michael Kubovy, The Psychology of Perspective and Renaissance Art. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Carlo Pedretti, Leonardo Architetto. Florence, Italy: Electa, 1978.

Leo Steinberg essay, “Leonardo’s Last Supper.” Art Quarterly, 1973.

Professor John H. Brown essay, “The Role of Monocular Viewing in Pictorial Appreciation.” Read at the American Society of Aesthetics Conference in San Francisco, 2003.University of Maryland’s Web site: http://faculty.philosophy.umd.edu/jhbrown/monoviewing/index.htm

Frederick Hartt, The History of Italian Renaissance Art. New York: Prentice-Hall and Abrams, 1969.

Catherine Harding. “Space, Illusion and Lived Realities in Early Renaissance Italy.” Oxford Art Journal 33.3 (2010) 396-99.