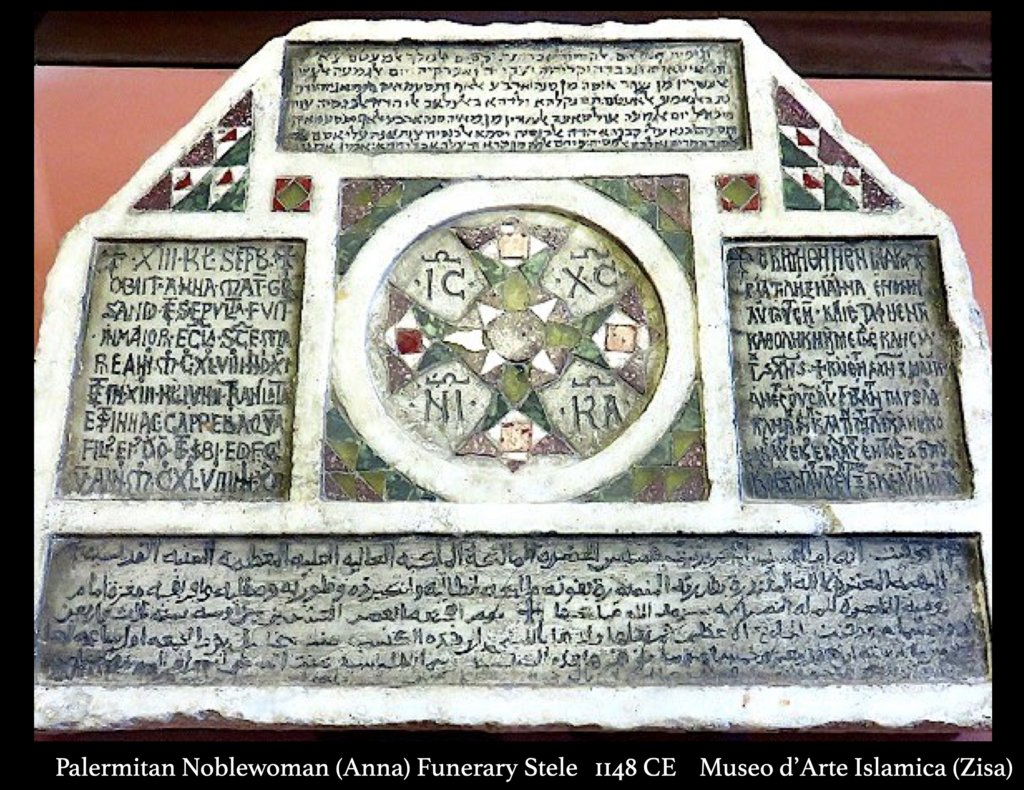

Quadrilingual Funerary Inscription – Hebrew, Latin, Greek, Arabic – in Palazzo Normanni, Palermo, 12th c. (photo P. Hunt).

By Anthony Klein –

The island of Sicily in the 12th century has long been portrayed as a golden age of multi-cultural amity resulting in spectacular wealth and a flowering of syncretic art and culture. Unlike contemporary Norman England, the conquering Norman French managed to weave together a successful working relationship with the indigenous groups they conquered, the former ruling Muslims, the substantial Greek Christian community, and the continuing minority Jewish community. This publication examines 12th century economic conditions on the island of Sicily; the legal, administrative, and cultural policies of King Roger II and his Norman successors that fostered a successful working relationship across linguistic, cultural and particularly religious divides; and the reactions and accommodations of those pre-existing communities, particularly the Muslim community, to their new circumstances under Norman Latin rule. Ultimately, I contend that these new Norman rulers, while driven initially by their relatively small numbers to permit local traditions and legal management to continue, eventually adopted policies and a court style that synthesized these various cultural/religious in order to maintain commercial success, to consolidate their rule, and foster an intellectually and artistically vibrant society that was the envy of their peers. Not without cause, and no doubt with substantial envy, Federico II (1198-1250) was one of their successors dubbed Stupor Mundi or “Marvel of the World” for his intellectual and cultural prowess and inclusivity.

Sicilian Trade in the 12th Century – Trade and Traders

The Sicily conquered by Roger II’s father benefited from superlative agricultural conditions and a robust trade, largely with North Africa and Egypt. Benjamin of Tudela, travelling around the Mediterranean and beyond in the 1160’s and early 1170’s, stopped in Sicily in 1172 or 1172 on his way back to Spain. In his chronicles, he clearly marveled at the natural agricultural abundance of Sicily, writing, for example, that Messina was “beautifully situated in a country, abounding with gardens and orchards and full of good things” and that the countryside around Palermo was “rich in wells and springs, grows wheat and barley and is well supplied in gardens and orchards.”[1] A Muslim traveler and chronicler named Abū al-Husayn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Jubayr similarly visited the island a decade or so later and also lauded the fecundity of Sicily as he was returning home to Andalusia from the Hajj. Ibn Jubayr described Western Sicily as “a line of continuous villages and farms…such as we had never seen before for goodness, fertility and amplitude; [like Cordova,] but this soil is choicer and more fertile.”[2] The few surviving court records, deeds, merchant agreements and the vibrant building program engaged in by the Normans all serve to attest to the wealth generated largely by Sicilian agriculture and trade.

Sicily during the time of Norman rule was a bountiful source of food products. As noted by Benjamin of Tudela, among others, wheat was a major source of revenue for Sicily, exported to North Africa, Egypt, and beyond. Sicilian wheat was also popular for Mediterranean sailors, given its durability during long sea voyages.[3] Naturally, under Muslim rule Sicily primarily exported its wheat to neighboring polities controlled by fellow Muslim leaders in North Africa and Egypt. Both Muslim and Jewish trading networks connected Sicily with the rest of the Maghrib.[4] This trade continued under the Norman kings, who facilitated the sale of wheat from their personal demesnes as well as from Christian and other landholders. In fact, wheat shortages in North Africa and the attendant famine there led to a brisk and profitable wheat trade for Sicily during this period.[5] Sicilians also exported other food products, including nuts, fruit, and cheese.[6] There was also an active fishing trade specializing in salted tuna.[7]

Textiles were another mainstay of Sicilian commerce during this period. Sicily produced cloth made from flax, cotton and silk.[8] The silk products were generally of middling quality and were traded largely into North African and Egyptian markets prior to the Norman conquest.[9] During the Norman period, silk exports may have declined coinciding with a decline in trade to the Muslim world following Sicily’s transition to Christian rule. However certain scholars posit that there may have been some increased export to Italy via Genoese and Pisan merchants that helped compensate for the decrease in trade with North Africa.[10] The Normans also encouraged the development of a higher-end domestic silk market which appears to have received a boost by the capture and forced relocation to Palermo of Jewish dyers from Greece in 1147. [11]

While trade requires surpluses to sell, it also requires the sellers to trade, and the systems to support them. Unsurprisingly, both Muslims and Jews were still actively engaged in the transport of grain and other goods from Sicily to North Africa. Correspondence collected and fortuitously preserved in the Geniza in Cairo show substantial trade managed by Jewish merchants in a number of goods prior to this period, including grain, flax and oil.[12] According to Smit, “Sicilian Christians must have been involved with the sale of grain within Sicily, as it was produced on estates controlled by Christians, but there is no evidence that they were participants in the transport of it to North Africa.”[13] Jews were actively engaged in silk and other textile processing and trade, as they also continued to be in the Byzantine Empire and other regions.[14] As Benjamin of Tudela made his way from his native Spain to Baghdad and back via Sicily, he catalogued the Jewish communities of the towns he visited, and it is quite apparent that many Jews were engaged in the cloth dyeing trade.[15] Muslims too were actively involved in the production of silk products, comprising the majority of silk embroiderers in Sicily.[16]

Evidence from surviving North African fatwas, loan documents, and other commercial documents show substantial ongoing cooperation among Christians, Muslims and Jews and between Sicily and North Africa. Meanwhile, it appears that Greek Christians largely in the eastern half of Sicily continued trade ties to the Byzantine Empire, and again Genoese and Pisan traders managed the trade routes to Italy via Messina.[17]

Trade Regulation and the Rule of Law: Law, Administration, and Tax Policy

As noted above, having goods to trade still requires a legal and administrative system that facilitates and even encourages such trade. According to Steven Runciman, “[t]he most remarkable feature of the Norman government was the success with which it brought harmony to the diverse elements in Sicily.”[18] It is arguable, however, how much this was a result of conscious policy versus a government passively enjoying the success of an already-thriving economy. To Smit, “[t]he Norman kings exercised some controls, for example over the circulation of coinage and a few industries in particular, but for the most part the merchants, often of other places, were the driving force in the commerce of the island.”[19] That may be the case given the relatively limited policing power that a government would have had in that era, but perhaps it undersells the contributions of the Norman government, which took positive steps to enhance trade and the rule of law while also maintaining policies that encouraged the presence and success of the merchants doing business in Sicily. In general, consistency in enforcement of laws often matters more than the content of the laws themselves. So long as the merchants could do business on predictable, fair and consistent terms, trade could thrive.

Initially, the Normal rulers permitted each of the different religious communities residing in Sicily to manage their own legal disputes in accordance with their own laws and customs. This likely resulted from limited administrative reach as Roger II consolidated power, combined with a purposeful royal policy to accommodate the various incumbent communities. By permitting the different religious communities to police themselves in accordance with their own laws and norms, the Normans were not required to maintain a large policing apparatus and the communities themselves had a stake in their own management — so that at least in daily affairs they could act as if little had changed. So long as the various communities acknowledged their new Norman lords, and paid their taxes, it was easier to let them manage themselves: “Throughout Sicily after the conquest, the local Muslim communities retained a kind of independence, able to live under the rule of their own qadis and qaids so long as they recognized the authority of the king and paid the jizya.”[20]

King Roger II, however, took several actions that led to a more centralized set of laws and administration to rule the kingdom. Around 1140, Roger enacted the Assizes of Ariano to centralize the foundations of law in the royal government. The Assizes of Ariano built upon various aspects of the laws governing his subject communities, including Norman law, Islamic law and the Code of Justinian, but applicable to all.[21] “The Assizes establishe[d] Roger’s status as a ‘princeps’, the prince of Justinian’s compilation, whose authority to promulgate, abrogate, and derogate law was unlimited.”[22] While the Assizes asserted the role of the king as the central executive authority, based largely on Byzantine precedent, they also acknowledged the unique multi-cultural and multi-ethnic setting of Sicily. For example, in his analysis, Pennington noted that the provisions regarding the legal status of villeins set forth in the Assizes mixed legal elements from the Code of Justinian with Islamic precedents to accommodate the existing social structures of Sicily.[23]

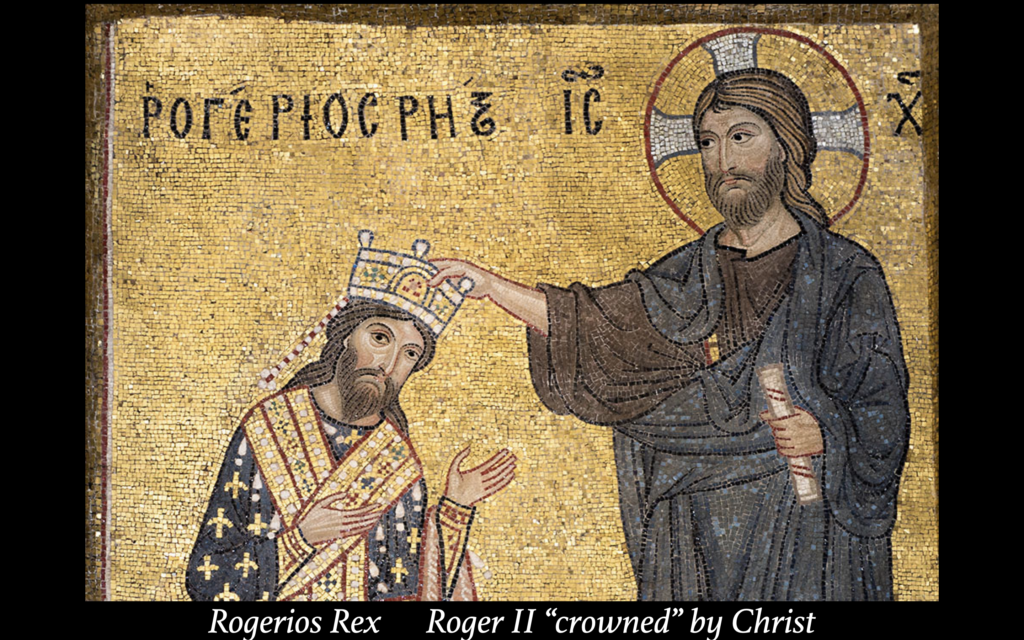

Propagandistic inclusive Rogerian art (Christ Crowning King Roger – “Rogerius Rex” in mixed Greek and Latin- dressed as a Byzantine ruler) in La Martorana Church, Palermo (image public domain)

As part of this centralizing function of the Norman royal court, Roger II also established a chancery to administer his domain, “manned by specialist and full-time personnel … with a clearly defined style of documentary production.”[24] Runciman describes King Roger’s Curia as a “curious synthesis of feudal, Byzantine and Muslim systems.”[25] Most of the chancery documents for Sicily, as opposed to the Italian portions of Roger’s kingdom, were in Greek while more local land transfer documents for Western Sicily and other Muslim areas continued to be issued in Arabic.[26] . While documents continued to be issued in Greek or Arabic, surviving documents indicate a material shift to Latin by the end of the 12th century, with the chancery becoming “an overwhelmingly Latinate institution.” as Latin immigration and landholdings in Sicily expanded.[27]

The adoption of a general set of laws for the disparate populations of Sicily as well as the creation of a multi-lingual centralized office to manage those laws created an administrative system where trade could flourish and wealth could accumulate, regardless of the ethnic or religious background of the subjects, and regardless of their native language. That that multi-cultural tolerance eventually broke down served to impoverish Sicily in more ways than one.

Monetary policy further buttressed centralized political control while filling the coffers of the Norman government. Merchants from North Africa in the 1140’s were required to exchange their dinars into Sicilian currency to conduct business in Sicily.[28] Their money was literally melted down in the official mints and recast as Sicilian currency with Norman iconography. Meanwhile, Roger II reformed Sicilian currency to incorporate both Arabic and Byzantine elements and to establish set exchange rates against both Muslim and Byzantine coinage to make conversion easier and international trade more fluid.[29] This served multiple purposes: demonstrating continuity with prior forms of currency, easing conversion with extant Arab and Byzantine currencies to benefit trade, and promoting the legitimacy of the issuing state.

Similarly, Norman tax policy was not simply limited to revenue generation but was also designed to shape the new kingdom. As with tax policy universally, a government’s decision what and how much to tax directly services to encourage some activities and discourage others. The court taxed inbound finished goods, outbound sales of raw materials, merchant shipping, monetary exchange and minority communities. Tax policy thus raised revenue but also encouraged conversion and assimilation, since Muslims and Jews were subjected to a poll tax, the jizya, as a similar tax under Muslim rule had encouraged earlier conversion to Islam. Conversely, the court offered tax breaks to encourage foreign merchants to trade with Sicily. These tax break facilitated the export of products, such as wheat, from royal demesnes. For example, William I issued a tax privilege to the Genoese in 1156, which covered sales of wheat, lambskins, meat and cotton.[30]

Basis of Norman Power; The Importance of Symbolism

So long as the local communities were allowed to largely administer themselves, maintain their faith, and continue to conduct business in accordance with largely pre-existing norms and customs, there were meaningful ongoing incentives for the various Sicilian communities to continue to cooperate, despite the changed nature of the regime governing the island and the imposition of a Latin Christian ruling class. Arguably, if the Norman rule had just taken a passive, laissez faire approach that might have achieved some of the same economic and social results. However, the Norman kings and their administrations, particularly Roger II, undertook a more proactive role, and thereby fostered the active engagement of their subject communities in Sicily to create a synthesis that was more dynamic and successful than it would have been if left alone. Whether through conscious policy or personal preference Norman rulers in parallel promoted a syncretic court culture, actively encouraging scholars of different backgrounds to come to Palermo and contribute.

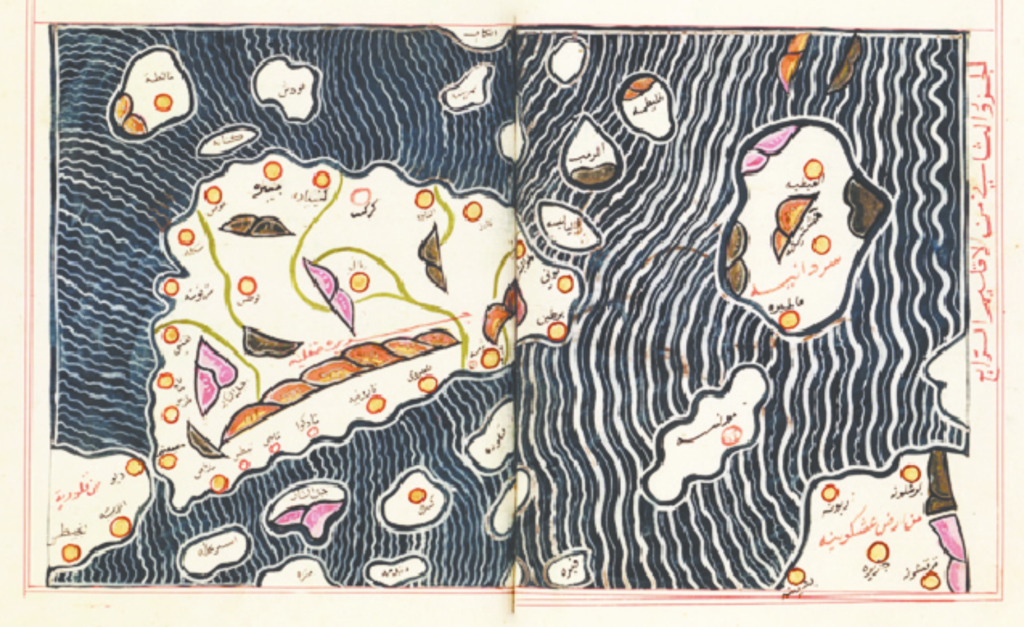

The Normans actively engaged Muslim and Greek scribes, scientists, geographers (and court officials to assist in the management of the kingdom. The administrators had titles that reflected the Norman borrowings; a mélange of Byzantine, Arab, Roman, and Frankish office names that mirrored the diversity of their backgrounds. For example, Roger II’s chief minister was a Greek from Antioch, while the chief minister for William II was a Muslim who had converted to Latin Christianity.[31] The Normans went a significant step further than just tolerating their Greek, Muslim and Jewish subjects; they consciously encouraged cross-cultural art and learning. As Hiroshi Takayama notes, Roger II employed both the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi as well as a Greek theologian named Neiros Doxopatres, among others.[32]Muhammed al-Idrisi emigrated to Palermo from North Africa in the 1140’s and among other works created a famous map of the world. His section map of Sicily viewed here below, ca. 1154, almost touching Calabria on bottom left, is upside down to normal view because south is at the top. Mt. Etna on the left side – looking like an inverted pink heart – is described as Jabal al-Na’ar or “Mountain of Fire”.

Muhammad al-Idrisi’s Map of Sicily (inverted), mid. 12th c. (courtesy of Bodleian Library, Oxford and Paul Chevedden in Al-Masaq 2010)

Doxopatres was a Constantinopolitan monk and theologian who also came to Roger II’s court in the 1140’s and published from there. The Norman kings engaged, and even imported (perhaps less forcefully than the unfortunate Jewish Greek silk dyers) Muslim and Greek artisans to construct and decorate their new palaces, gardens and churches.

According to Arab historians, such as Ibn al-Athir and Ibn Jubayr, the rulers could speak and understand Arabic and even seemed to prefer to have Muslim advisors and pages.[33] Whether this was actually the case, the idea that Muslim writers and travelers would have this view would have helped the incumbent Muslim population to accept their new Norman rulers. Of equal importance, the Norman kings were willing to capitalize on the abilities and connections of their subject populations, taking the best of what they had to offer so long as they worked within the system.

Finding themselves in a land of superior natural resources, and at a crossroads of trade throughout the Mediterranean, it seems natural that the Norman rulers would want to take advantage of the best that the various communities had to offer and benefit from continuity. They did not just passively continue existing structures, nor did they just impose a completely new structure at the expense of existing structures to confirm and enhance their power. Rather, they asserted control by adopting the symbols and language of the existing populations in a manner that would best resonate with their new, disparate subjects.

More prosaically, having Arabic seals on contracts, or signing proclamations in Arabic or Greek, indicated to the existing commercial and administrative populations that the new Norman rulers were one of them and that to a large extent business could continue as usual. According to Johns and Jamil, the Norman trilingual chancery was a “deliberate creation of King Roger.”[34] Furthermore, they note that Roger specifically imported scribes, and with them familiar forms and practice, “not in order to issue Arabic documents to their Arab subjects, Greek to the Greeks, Latin to the Latins — but rather to enhance the image of the king.”[35] Johns and Jamil analyzed the Arabic signature blocks (‘alama) of Roger II and a minister under William II to test whether the use of these signature blocks displayed actual Arabic fluency from the Normans, or rather whether the use was more tactical. On balance, they found that the use of ‘alama did not show any actual Arabic fluency but only that the appearance of following Arabic forms was useful to each of them. Johns and Jamil also noted that much of government business was conducted in Greek in the early to mid-12th century and only rarely were ‘alama appended to government documents.[36] The example from Roger II is a document about a property transfer to endow Santa Maria dell’ Ammiraglio in 1143. The document that contains the ‘alama of Roger II is in both Greek and Arabic. The use of the ‘alama plus the bilingual nature of the document likely both serviced to confirm that the transfer of Muslim property would be memorialized in a way that all interested parties would acknowledge the propriety of the transfer. Johns and Jamil describe the presence of the ‘alama as a “deliberate fiction that contributed to the illusion that they resembled Muslim rulers.”[37] However, I contend that even if the Christian rulers and ministers were not actually fluent in Arabic, that does not lessen the importance of the perceived need occasionally to appear to be so.

Johns and Jamil posit the same rationale for the creation of the new churches in Sicily.[38] The Norman rulers imported mosaicists from Byzantium, painters from Egypt and masons from Italy to help create a synthetic iconography to represent the Norman rulers as a continuation of, and evolution from, Greek and Muslim observance. By combining stylistic elements and symbolism from both traditions, the Norman kings could make the introduction of Latin Christianity appear to be more organic than in truth it actually was. For example, the Martorana mosaic of Roger II in the Church of Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio in Palermo portrays Roger in the regalia of a Byzantine emperor even though he was a Latin Christian king in the Western mold. In a similar vein, Roger II’s mantle (now in Vienna) exhibits strong stylistic influences from the Islamic world.[39]

The Role and Subsequent Reactions of Muslim, Greek, and Jewish Populations

In the early years of the Norman Sicilian kingdom, Sicilians still largely followed the cultural norms and styles they had followed when under Muslim rule. That naturally changed over time both as the Normans became more entrenched as rulers of Sicily, but also as new Latin Christian Italians migrated to Sicily and as the Arab presence as integral members of the coastal communities diminished and as the period of their rule faded further and further into the past.[40] For example, Smit quotes Benjamin of Tudela’s observations regarding what he saw in Messina:[41]

Messina still sounds and behaves as though it were a Muslim city. On the streets most people (including Jews) speak Arabic, and bands play Muslim music. Torchlight processions accompany weddings, and professional mourners accompany funerals in accord with Muslim custom. The Muslim women cover themselves completely and some of the older Christian women follow their example. On this island of many natural riches and many peoples, Christians, Muslims, and Jews may freely celebrate their religion.

Again, per Smit, ibn-Jubayr noted the substantial, even integral, Muslim presence at the court of William II:[42]

Their King, William, is admirable for his just conduct, and the use he makes of the industry, and for choosing eunuch pages who all, or nearly all, concealing their faith, yet hold firm to the Muslim divine law. He has much confidence in Muslims, relying on them for his affairs, and the most important matters, even the supervisor of his kitchen being a Muslim; and he keeps a band of black Muslim slaves commanded by a leader chosen from amongst them.

As revealed by Ibn-Jubayr’s writing, for Muslims it was an uncomfortable and eventually losing accommodation. The hint about “concealing their faith” indicates that even in a court that relied on and may have reveled in a number of Muslim forms and practices, there was pressure to be Christian to serve in government. Throughout the 12th century and beyond, the Muslim community in Sicily continued to be vital to the society as a whole and played a substantial role in all aspects of commercial life, as well as a substantial administrative and military role, even if the period under review represented a gradual retreat from dominance and eventual elimination in the 13th Century.[43]

In addition to the evidence for Muslim ambivalence found in the writings of Ibn al-Jubayr, fatwas issued by Muslim clerics in North Africa in response to newly Christian Sicily also reveal the difficulty for Muslim authorities and communities to navigate life under Christian rule. In a series of fatwas issued over time, a North African jurist, Imam al-Mazari, acknowledged the need to recognize Islamic decisions issued in Christian-occupied Sicily, but also discouraged trade with Sicily – even in the circumstances where famine in North Africa would benefit from continued grain purchases from Sicily.[44] This was based in part on religious proscriptions against living in non-Muslim ruled lands regardless of whether or not the non-Muslim rulers treated the Muslim population well.[45] In fact, if the subject Muslim population was well-treated, that created an extra layer of threat to lead the Muslim population away from Islam.[46] Regardless of the principle requiring emigration and the occasional legal rulings, of course trade continued between Norman Sicily and Muslim North Africa, both as a result of need and for profit.[47] In the fatwa upholding Sicilian Muslim legal jurisprudence, al-Mazari found that the jurist had sufficient reason to stay in Sicily despite its Christian rulers and therefore the rulings should be respected as if the Sicilian jurist had been appointed by a Muslim ruler.[48] From a practical perspective, al-Mazari recognized the need to have empowered Muslim judges to resolve disputes and provide leadership. Al-Mazari also issued fatwas on various trade disputes involving North African and Sicilian merchants. On the one hand, this serves as incidental evidence of continuing trade connections between the two lands despite the religious differences, but the rulings themselves indicate that from a religious perspective such trade was discouraged.

Conclusion

From the formal designation of Sicily as a kingdom under the rule of Roger II in 1130 to the death of his grandson William II in 1189, the island of Sicily enjoyed a period of economic success that was fostered by its new Norman rulers, and a related period of artistic and cultural creativity and vigor that was likewise fostered and paid for by its Norman rulers. During this period, Muslims, Jews, and Greek-speaking Christians following Byzantine church practice could all continue largely as they had before, engaging in trade and following customs and laws with which they were familiar. While Eastern Sicily became increasingly Latin Christian, based substantially on immigration, but also as a result of anti-Muslim pogroms in the 1160’s, Palermo and Western Sicily maintained a strongly Muslim character as part of its mix. Partly as a matter of court policy to establish sovereignty, but also likely because they themselves culturally embodied and relished the cultural mix around them that they could draw upon for their palaces, gardens and churches, the Norman kings presided over a very rare period of relative religious amity that resulted in prosperity enjoyed at the time and artistic achievements that we still marvel at today. As Runciman put it, “The Norman kings, ambitious and unscrupulous though they were, must be given credit for this extraordinary achievement.”[49]

Bibliography

Abulafia, D. (1983). The Crown and the Economy under Roger II and His Successors. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 37, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291473

Benjamin, of T., Asher, A., Zunz, L., & Lebrecht, F. S. (1900). The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela. New York, “Hakesheth” publishing co. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/itineraryofrabb01benj

Davis-Secord, S. (2007). Muslims in Norman Sicily: The Evidence of Imām al-Māzarī’s Fatwās. Mediterranean Studies, 16, 46–66.

Jacqueline Alio & Louis Mendola. (2013). The Peoples of Sicily: A Multicultural Legacy.

Johns, J., & Jamil, N. (2004). Signs of the Times: Arabic Signatures as a Measure of Acculturation in Norman Sicily. Muqarnas, 21, 181–192.

Loud, G. A. (2009). The Chancery and Charters of the Kings of Sicily (1130-1212). The English Historical Review, 124(509), 779–810.

Pennington, K. (2006). The Birth of the Ius commune: King Roger II’s Legislation. Rivista Internazionale Del Diritto Comune 17.

Steven Runciman. (1958). The Sicilian Vespers, A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

Takayama, H. (2003). Central Power and Multi-Cultural Elements at the Norman Court of Sicily. Mediterranean Studies, 12, 1–15.

Timothy James Smit. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota.

Travaini, L. (2001). The Normans between Byzantium and the Islamic World. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 55, 179–196. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291817

[1] Benjamin, of Tudela. The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela (A. Asher, Trans.). New York, “Hakesheth” publishing co. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/itineraryofrabb01benj

[2] Smit, T. J. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota, 60, quoting Ibn Jubayr, The Travels of Ibn Jubayr, Being the Chronicles of a Mediaeval Spanish Moor Concerning his Journey to the Egypt of Saladin, the Holy Cities of Arabia, Baghdad the City of the Caliphs, the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily. London: J. Cape, 1952, p. 350.

[3] Ibid, p. 65; see also, Abulafia, D. (1983). The Crown and the Economy under Roger II and His Successors. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 37, 1–14, p. 4. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291473

[4] Smit, T. J. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota, pp. 21, 32, 162.

[5] Abulafia, D. (1983). The Crown and the Economy under Roger II and His Successors. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 37, 1–14, p. 4. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291473

[6] Smit, T. J. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota, p. 85.

[7] Ibid, pp. 48-49, citing Benjamin of Tudela.

[8] Ibid, p. 174.

[9] Ibid, p. 180.

[10] Ibid, p. 65.

[11] Ibid, p. 184-185.

[12] Ibid, p. 162.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, pp. 182-183.

[15] Benjamin, of Tudela. The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela (A. Asher, Trans.). New York, “Hakesheth” publishing co. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/itineraryofrabb01benj

[16] Smit, T. J. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota, p. 182.

[17] Ibid, p. 32.

[18] Runciman, S. (1958). The Sicilian Vespers, A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, p. 9.

[19] Smit, T. J. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota, p. 157.

[20] Ibid, p. 84.

[21] Alio, J., & Mendola, L. (2013). The Peoples of Sicily: A Multicultural Legacy, p. 282.

[22] Pennington, K. (2006). The Birth of the Ius commune: King Roger II’s Legislation. Rivista Internazionale Del Diritto Comune 17.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Loud, G. A. (2009). The Chancery and Charters of the Kings of Sicily (1130-1212). The English Historical Review, 124(509), 780.

[25] Runciman, S. (1958). The Sicilian Vespers, A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

[26] Loud, G. A. (2009). The Chancery and Charters of the Kings of Sicily (1130-1212). The English Historical Review, 124(509), 780-781, 792.

[27] Ibid, pp. 793-794.

[28] Travaini, L. (2001). The Normans between Byzantium and the Islamic World. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 55, 183. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291817

[29] Ibid, p. 184.

[30] Abulafia, D. (1983). The Crown and the Economy under Roger II and His Successors. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 37, 4. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291473

[31] Takayama, H. (2003). Central Power and Multi-Cultural Elements at the Norman Court of Sicily. Mediterranean Studies, 12, 1–15.

[32] Ibid, p. 6.

[33] Ibid, p. 8.

[34] Johns, J., & Jamil, N. (2004). Signs of the Times: Arabic Signatures as a Measure of Acculturation in Norman Sicily. Muqarnas, 21, 181.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid, p. 182.

[37] Ibid, p. 184.

[38] Ibid, p. 181.

[39]Smit, T. J. (2009). Commerce and Coexistence: Muslims in the Economy and Society of Norman Sicily. University of Minnesota, p. 182.

[40] Beyond the scope of this paper, the Greek Christians eventually converted to Catholicism and the island eventually developed a new Sicilian version of Italian that replaced Greek and Arabic. Equally beyond the scope of this paper, the remaining Muslims that had not previously converted or emigrated were expelled, as were the remaining Jews after 1492.

[41] Ibid, p. 65.

[42] Ibid, p. 69.

[43] Abulafia, D. (1983). The Crown and the Economy under Roger II and His Successors. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 37, 11. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291473

[44] Davis-Secord, S. (2007). Muslims in Norman Sicily: The Evidence of Imām al-Māzarī’s Fatwās. Mediterranean Studies, 16, 47-48.

[45] Ibid, p. 52.

[46] Ibid, p. 53.

[47] Ibid, p. 55.

[48] Ibid, p. 58.

[49] Runciman, S. (1958). The Sicilian Vespers, A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, p. 10.