By Patrick Hunt –

Seldom has ancient literature been so psychologically riveting as the biblical peripety of David and Bathsheba in 2 Samuel II and following to the conclusion of the book with David’s diminished end. King David’s multiple mistakes with Bathsheba – adultery and the requested murder of her husband Uriah – are meticulously narrated. Bathsheba’s bathing that caught David’ eye has been the famous subject of many painters, including Jan Massys (1562, Louvre), Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 & 1637 in multiple venues including Columbus Museum of Art), and Rembrandt (1654, Louvre) among many others. The French historical and Academicism painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), sees exactly where the sequence of David’s sins led. Having traveled widely in the Near East, his above carefully-constructed landscape with Bathsheba (Bethsabée) imparts the biblical cheesecake rationalization of voyeuristic nudity. He has the bathing Bathsheba almost gyrating for the viewer with David leaning out of his palace tower to the left.

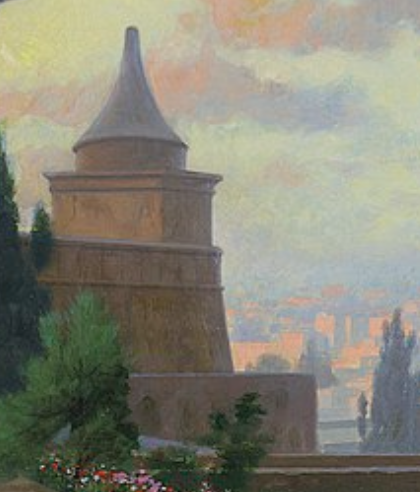

The view from the rooftop is a fairly-realistic Jerusalem looking west toward Zion hill from the Ophel ridge where David’s Palace was, with even the then-contemporary to 1889 monuments of the Armenian Quarter visible on the horizon. But Gérôme has cleverly added a sombre proleptic device in the landscape: David’s palace on the left the palace terminates in a tower that is the exact profile and hues of what has been known as Absalom’s Tomb (or Absalom’s Monument, Yad Absalom) in the Kidron Valley of Jerusalem. This is almost the identical view I remember when I lived in Jerusalem on Mt. Zion (1984-85) and walked multiple times past Yad Absalom in the Kidron valley during archaeological training as a graduate student. This is where the sad narrative culminates with more death and loss. Absalom’s so-called tomb Yad Absalom is actually itself 1st c. CE, although there may have been a much earlier tomb in this space judging by the original hole before the carved out recess was made in the cliff face and before the current structure was added in a conflated episode over centuries.

Yad Absalom 1st c. BCE but with a possible earlier opening, Kidron Valley, Jerusalem

Why has Gérôme added this same well-known monument in his ekphrastic painting? I suggest that it is because Gérôme’s research included knowledge of Yad Absalom and he alludes here to the concatenation of David’s sins with Bathsheba causing multiple ensuing tragedies in the law of unintended consequences where “error begets error” leading a generation later to Absalom’s tragedy.

In 2 Samuel 12:1-10 the prophet Nathan excoriates David over his deliberated sins with Bathsheba and prophesies that the metaphorical sword will never leave his house (12:10) and following that someone close to him will take over his harem (12:11) in public after David plotted in private. This is all because David committed adultery with Bathsheba then tried to get her husband Uriah to come home to his wife when Bathsheba becomes pregnant by David in her husband’s absence (2 Samuel 11: 1-5, 6-13). Uriah perished when David commanded Joash to place him in the thick of battle at Ammon’s gate to get rid of him (11:14-17). A generation later, David’s son Amnon will rape his half-sister Tamar (2 Samuel 13) and be murdered in retaliation by her full brother Absalom. Then after his fugitive exile is ended, rebellious Absalom will sleep with his father’s concubines in his father’s palace during his usurpation of Jerusalem (2 Samuel 16:22) before David’s restoration and Absalom’s own tragic death at the hands of Joab, David’s warlord.

The connection of Absalom to this monument still called Yad Absalom was certainly well-attested over millennia (Josephus even identified a structure of Absalom in his Antiquities of the Jews 7.10.3 although not likely the same structure) even if the actual monument surviving today may not be Absalom’s. 2 Samuel 18:18 relates: “During his lifetime Absalom had taken a pillar and erected it in the Kings Valley as a monument to himself, for he thought, ‘I have no son to carry on the memory of my name.’ He named the pillar after himself and it is called Absalom’s Monument to this day.” Tradition and perception here may be more important than archaeological fact, but in the literary narrative it was certainly tragic that David lost at least two or three of his children – Amnon, Absalom and to all extents Tamar whose life was ruined – because of his own irresponsible behavior and lack of control of his libido. Having visited Jerusalem in 1856 where Gérôme would have almost certainly seen and heard sufficient tradition about Yad Absalom, this combined textual and visual tragedy of ultimately Absalom and David’s dystopic immediate family future is what Gérôme seems to be painting in the law of unintended consequences in such careful detail.

Notes:

Madain Project: Yad Absalom (https://madainproject.com/tomb_of_absalom).

H. Hornick, I. Boxall, B. Dykema, eds. The Art of Biblical Interpretation: Visual Portrayals of Scriptural Narratives. Society of Biblical Literature Press, 2021, 27, 250.

Patrick Hunt. “Bathsheba: Rembrandt’s Confession.” Electrum Magazine, November, 2015 (https://www.electrummagazine.com/2015/11/bathsheba-rembrandts-confession/).