By Walter Borden, M.D. –

Before the beginning there was mythology, mysticism, a miasma of beliefs. Might was right, savagery ruled. It was truly dark. Then, in the 6th century BCE, a burst of light, a blossoming, a cultural epiphany, the birth of the first Enlightenment in classical Greece.

The light was the emergence of scientific thinking. Science is the recognition of the laws of nature combined with a search for their understanding. It is critical thinking. Psychiatry (from psyche, a Greek for soul among other meanings) and iatros, a Greek word for a healer or doctor) is the science of human nature. Ultimately psychiatry – anticipated by the Greeks medical tradition established at Asklepian healing sanctuaries like Epidauros – is the science of emotional pain, of thinking, of pleasure, the self, relationships, personal and group connectedness, in other words, what makes us human. We are capable of acting at odds with what makes us human and to our own survival. We can commit genocide based on scapegoating, racism, myth, or fear of “the other”. We become bedeviled by our root savagery, the various forms of greed, and of course the scourge of revenge.

Human history has been a roller coaster with reversals into savagery and corrections back towards civilization. In recent years we appear to have fallen into another reversal and/or become numbed by a kind of cultural post-traumatic stress disorder.

We’ve become seemingly indifferent to horrors that fill the daily news. Large swaths of our population, like Lemmings, blindly follow a cult leader over the cliff to the barbaric rocks below. Civilization, despite truly marvelous technological advances, is threatened by a seductive pull backwards, by demagogues who exploit passions, grievances, fears, greed and legacies of rage. Where is humanism? What is humanism?

There are many branches of knowledge that have contributed to our understanding of human nature, but the theatre has been uniquely effective. After all, its prime purpose is to engage the audience. The human drama on stage emotionally resonates with the audience lending power to the message of humanism. Those in the audience reacting according to their unique sensibilities, can identify with the characters, relationships and/or issues.

The playwrights, Aeschylus, Shakespeare, O’Neill with artistic mastery, projected humanism on the complicated palette of grief as core of what makes us human. Ironically, grief has become the neglected step child of modern psychiatry.

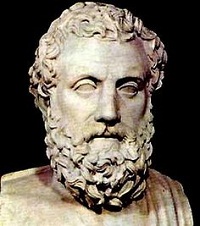

Although separated by chronological time, these authors share a unique circumstance in that their talent was seemingly sparked to bloom by agonizing personal loss. Aeschylus produced his best tragedies, indeed he created tragedy as an art form, style, structure and theme following the death of his brother who fought beside him at Marathon. In Fagles’ foreword to his translation of the Oresteia he presents Aeschylus’ tragic vision as the spirit of human culture, of suffering and regeneration, likened to the cycle of the seasons, or rites of passage. The Oresteia represents the rite of passage from savagery to civilization, from revenge justice to democratic justice. Although the iconic tragedy, the Oresteia does not end in despair. It ends on a joyful note with the transformation of the Furies, representing savage revenge, into the guardians of the rule of law.

His best writing sprang from his grief after his brother died beside him at the Battle of Marathon, 490 BCE. They’d enlisted together to fight the invading Persians, ancestors of Iran, and even then, an enemy of western ways. Aeschylus saw his beloved Koryenous hacked to death by the Persians. His grief fermented—metabolized—blossomed (sprouted if you will) in his drama.

His profound insight: unspoken grief is unresolved grief, that can smolder and become obsession, leading to madness and murderous retaliatory rage, only breeding more violence. He added: words are physician to the mind gone mad. In other words, giving voice to pain has healing power. From his own life and personal pain, he created a tragic drama that touched the deep need for psychological healing in a people that had experienced overwhelming losses from plagues, terrible wars, cycles of retaliatory violence, and the impact of social changes as the Bronze Age gave way to early modern civilization.

Until Aeschylus, drama was two-dimensional. In the ancient epic/lyric form, there is one actor, the hero, and the chorus, which represents some facet of the voice of humanity. The hero is defined, and engulfed, by external forces that grow stronger as he struggles against them. The character of the hero is almost irrelevant; he is pushed and pulled by destiny’s demons. The chorus, a communal voice with a character of its own, is the protagonist and defines the issues—usually grand communal themes, such as the polis, the defeated and/or the victimized—by focusing them on the single actor through a prism of moral force. Chorus and actor are in reciprocal relation. As the crisis develops and tension builds, the focus shifts. The actor becomes protagonist, the center of the moral struggle, which ends with the hero facing the crisis and making his decision. In the lyric epic, the initial situation never changes. The plot remains the same as in the first ode, when the actor enters and reveals the general situation. There is no moving plot. The only action is the increasing tension within the hero. There is no way to change perspective, to bring in another’s view of and interaction with the hero or situation, or to add information unknown to the hero that might change the situation. There is no way to change the parameters defined in the first ode, no way to move the plot along to bring action into the play. Temporal perspective and character definition are both impossible in such a scheme.

Aeschylus, in a creative leap, adds a second actor, which brings movement to the plot and shifts the focus onto character. The second actor introduces new information, such as relevant events that would be impossible for the hero to know, events that may drastically change his circumstances. An old family employee can come onstage with news that the hero’s wife is really his mother, or a messenger arrives to tell him that the presumed dead son is alive and has returned with murder in his heart, or that the opponent he is going to fight to the death is really his brother. The plot moves and thickens. Moreover, interactions between characters add definition and dimension to their development.

In another creative leap, Aeschylus modified the structure of the trilogy, linking three plays in a series with a unified theme. The concept of linked acts—action over time with continuity of motif—enables evolution of plot and issues associated with the generation of inner drama in the hero. Trilogy, as used by Aeschylus, can best be understood as the ancestor of the three-act play. Using this structure, he was able to portray the transfer of influences from person to person, generation to generation, within a family and within a people. He was able to depict personal change, growth, and decline. He could dramatize the legacy of emotions—a sense of obligation, a sense of guilt—that passed from fathers to sons and daughters and on to future generations. He could describe the harbingers of madness and the long-term effects of grief, abuse, conflict, and violence—thus showing that retaliatory violence, even in the name of justice, only breeds more violence, that oppression of women and children makes them violent in turn, that brutality is destructive to society. He was able to show that unspoken grief results in an inability to come to terms with the past and leads to the reenactment and perpetuation of old conflict and pain. His dramas were the first psychiatric studies.

If Aeschylus helped lay the foundation of psychodynamic psychology, he was also a consummate advocate for the incorporation of psychological understanding in democratic justice. He dealt with the issue of criminal responsibility when madness is an element of criminal behavior.

He had a great influence on literature, theatre, political and social life throughout the ages. Shakespeare in Hamlet and Merchant of Venice echoes Aeschylus in warning of the destructive power of revenge, as does O’Neill in Desire Under the Elms, and Mourning Becomes Electra. More recently: quoting Aeschylus, Robert Kennedy said, “Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God… dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and to make gentle the life of this world.”[ Speech on the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Greek people did not listen to the tragedians. The twin social parasites, greed and hubris, latched on to the germinating humanism sucking its life, exhausting it by aggressive expansion, and then a draining war with Sparta. Biologic plague compounded the social illness. Despite attempts by Pericles to keep alive the values of what was a Golden Age, that First Enlightenment was weakened from within and overshadowed by the rise of majestic Rome.

A Roman jurist, stateman, orator, Cicero, had lived in Athens and absorbed the values of their rich culture. He carried the essence of classical culture, values of humanism, to Rome. His writings were to serve as its seedlings. Indeed, Cicero coined the word Humanitas. The Roman Republic too was infected by the twin social diseases and destined to succumb. The terminal illness was long and painful. The flower of civilization was fragmented and wilted beneath the magical thinking, mysticism and savagery that rushed in to fill the void. Our early middle ages, called Dark Ages saw an increasingly reactionary theology attempting to hold onto at least a semblance of civilization. In that dark winter season, Cicero’s writings, like seeds of civilization, lay beneath the surface, waiting.

Our medieval period, or middle ages, was characterized by a rigidly controlling Catholicism, a structured oppressive ideology attempting to instill order, to contain the chaotic currents of a world transforming. But those currents, passions, when stifled ferment into vinegar rather than wine, and seep through the cracks in the form of cruelty and intolerance especially to “the other, coming out as the Inquisition.

Civilization, however, was not to be denied. Two Italian scholar-poet philosophers, history detectives, Poggio (1380-1459) and Petrarch (1304-1374) uncovered embryos that together germinated as the Renaissance. Poggio delivered the Italian poet-philosopher, Lucretius, author of On the Nature of Things,

Lucretius (50’s BCE), wrote a translation and interpretation of the Greek philosopher Epicurus into Latin, On the Nature of Things. Amongst moral and philosophical issues, this work included the fundamental concepts of an atomic theory and evolution. The history of Lucretius is a mystery. It appears that his work languished in the dim light of that era, and might be considered a premature growth peeking through the frozen winter frost.

Poggio was part of a nascent humanist movement that looked to revive the classics that were rising to the surface and spilling forth in what became known as the Renaissance. The essence of which can best be defined as Protagoras’ “man is the measure of all things” at the center of which is a scientific naturalism, a humanism centered on the dignity of all persons.

Spring arrived when the second Italian scholar, Petrarch, rediscovered Cicero’s writings. Cicero, an Italian Renaissance man before the Renaissance, was a Roman lawyer, politician, writer who coined the term Humanitas. He had immersed himself in Greek classics and carried Golden Age values to Rome. Those values long hidden had been simmering and bubbling for many years.

As the Middle Ages merged with Renaissance, European culture experienced a spring-like opening, throwing off the shackles of religious orthodoxy, releasing the freedom to think critically, to be curious, to experiment, to create. The printing press unleashed the new ideas and classically tinged humanism. An offshoot of the new freedom, the Reformation, led to more religious tumult. There were social implications as well. This was felt in England as a combination earthquake and eruption, an upsurge of grievances, long repressed, and a boiling of the under classes.

This was accompanied by an increasing growth of antisemitism. Jews were first brought to England by William the conqueror in 1086. He brought them to exploit their financial skills necessary for his growing economy. Because the Christian church at the time prohibited interest on loans, the king’s banks were at a disadvantage unless they used Jewish money lenders who were not so prohibited. At the same time Jews were prohibited from all occupations except lending money. This placed them in what later psychologists called a double bind. Their social position was more than awkward, making them pariahs, and an ideal target of scapegoating. Antisemitism reached a crest in 1290 with the Expulsion of the Jews. In 1290 AD there were approximately 2000 Jews in England who were expelled to France. They were not to return.

In England Elizabeth I attained the throne. Catholicism was replaced by the more tolerant Church of England, and it was a time of exploration, expansion, and cultural blooming. With more tolerance Jews were invited back in 1657. The Renaissance religious wound was bleeding into what was to become the Elizabethan era. Catholicism did not disappear with Elizabeth’s swipe of the quill. There was ongoing conflict. But there was relative peace compared to pre and post Elizabeth.

What was newly permissible on the stage contributed to the increasing popularity of theater. The London stage became a megaphone for public discourse and discontent. It was a tumultuous era. It was in this setting that John and Mary Shakespeare gave birth to their first born son William.

John Shakespeare was a successful glove maker. He was a very ambitious man with tendencies to overreach, and whose history confirms Heraclitus’ “character is destiny”. Shakespeare’s father was a money lender on the side, and dabbled illegally in the wool trade as well. Active in local politics he appears to have been something of a wheeler dealer. He was preoccupied with image, but was forced to resign as his conflicts with the law became more public, and his financial affairs unraveled. John Shakespeare’s public disgrace, and his character flaws had some impact on young Will’s skepticism of officialdom and keen eye towards the hypocrisy of authority.

This was also a time of religious upheaval; the overturning of Catholic order was accompanied by cruel punishments for differences. Punishments included public displays of beheadings, flogging, and mutilations. The flagrant cruelty must have had an impact on any with even the slightest sensitivity.

Little is known of Shakespeare’s personal life, which despite innumerable rumors and speculations, remains a mystery. We know he married Anne Hatheway when he was 18 and she 26, that their first born, Susanna was born 6 months later, and twins, Judith and Hamnet two years later. Of his marriage he revealed nothing, the empty space suggests a troubled relationship. The loss of their son Hamnet at age eleven, probably from plague, must have been cataclysmic to both parents and their relationship. In any event, for most of his married life he lived apart. without correspondence between husband and wife, and Anne Hatheway is not mentioned in his will, except for the pithy bequest to her of “the second best bed”. While the meaning of this has been debated, it does appear to be typical Shakespeare in its teasing opacity. While he did return to Stratford from time to time to conduct business, there does not appear to be any expressed marital bond. A cold war appears the best description. In the meantime Will was actively involved in a social life with at least one mistress, but he avoided the “debauched” life of many of his fellow actors and writers. Shakespeare’s principal colleagues, competitors, and critics were Marlowe and Greene. Both were of a higher social caste in an England where stratification and caste were defining, and restricting of identity. They also were brilliant, arrogant, uncontrolled, cruel and amoral. They probably also resented Will’s abstention from decadence as well as daring to violate class boundaries. In contrast, Shakespeare was determined, disciplined, committed to his art.

While Shakespeare was writing King John he was informed of his son Hamnet’s death, and wrote Hamlet in the wake of his loss. The merging of names cannot be coincidence. The following gives a peek at Shakespeare’s grief.;

“Grief fills the room up of my absent child.

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me.

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words.

Remembers me of all his gracious parts.

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form.

Then, have I reason to be fond of grief.”

““My grief lies all within

And these external manners of lament

Are merely shadows to the unseen grief

That swells with silence in the tortured soul.”

“Give sorrow words. The grief that does not speak whispers the o’er-fraught heart, and bids it break.”

This echoes Aeschylus’ Oresteia, that frozen, unspoken grief can lead to madness and homicide. His: words are physician to the mind gone mad, anticipates modern dynamic psychiatry. Put simply: talking, sharing emotional pain, such as the pain of loss, opens a path to healing. It means that sharing pain creates a bond. You do not walk that path alone. Both Aeschylus and Shakespeare shared their pain through their art. Hamlet also shares the Oresteia theme of duty to the dead, the conflicts engendered, and the destructive consequences of revenge.

While the famous soliloquy of Hamlet has been interpreted as an ode to suicide, there is another interpretation. “To be or not to be” can mean to be what’s in you to be, not succumb to other’s expectations or lack there-of. In other words “To Be” can be a statement of personal autonomy. If we look at Shakespeare’s personal history, sparse as it is; no doubt due to his personal reticence to revealing himself, he pulled up his roots in Stratford and set them down on London’s stage. He’d decided to be, to grow—what was in him to be. And, like Aeschylus coming of age during a transformational era Shakespeare created a new form of drama in which he combined tragedy, comedy, satire and history. His drama portrayed human nature from its heights to depths. And like Aeschylus Shakespeare’s creativity was fertilized by loss. His greatest tragedies came after his personal tragedy, the loss of his son Hamnet.

The Merchant of Venice is an example of Shakespeare’s understanding of the complexity as well as depth of human nature. Shylock, although portrayed as a “monster”, the stereotypical, greedy, blood thirsty poster Jew, he makes clear Shylock is but the product of the abuse he has experienced at the hands of anti-Semites. In that respect there is resonance with another author, Euripides, whose “monster”, Medea, was the result of the brutal cruelty she experienced. The point: “monster” humans are indeed hard to see as human, but if human beings are treated inhumanely it is no surprise to get inhumanity.

Eugene O’Neill although millennia removed from Aeschylus also lost a beloved brother. He also lost two sons to suicide, and his mother to narcotic addiction, probably the result of depression from loss of an infant son, Edmund, two years prior to Eugene’s birth. Ironically, her addiction had been attributed to Eugene’s birth, and, to compound the irony, Eugene’s brother, Jamie, was blamed for Edmund’s death. Blame and guilt following a death are recurrent themes, wrapped in denial and acted out in relationships, alcoholism, drugs, destructive and self-destructive behavior.

O’Neill acknowledged his griefs as the wellspring of his creativity. In his autobiographical Long Day’s Journey Into Night, he transforms the complex agonies of his family into living metaphor that resonates with the humanism of the audience.

Mourning Becomes Electra is in fact a trilogy of kindred spirit and resonates with Aeschylus’ Oresteia. It tells the story of a seemingly cursed conflicted family at the end of the American civil war, haunted by the plagues of filicide, slavery, betrayals, adultery, revenge homicide and matricide.

The Iceman Cometh is a play with a theme of pipe-dreams (fantasies) representing the defensive distortions of threatening unconscious issues. It is as if the ice pipe-dream as it melts reveals the underlying reality, more nightmare than dream. (guilt resulting in homicide, and in another character, suicide).

These authors explored the human soul, mind and heart, bringing to light what makes us human, but not papering over the dark recesses, the savage roots, that in every age struggles to strangle the flower of civilization. It is that very same struggle we face today.

Walter Borden, M.D. is a Distinguished Life Fellow, American Psychiatric Association; Diplomate, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and Diplomate, American Board of Forensic Psychiatry.