By Timothy Demy –

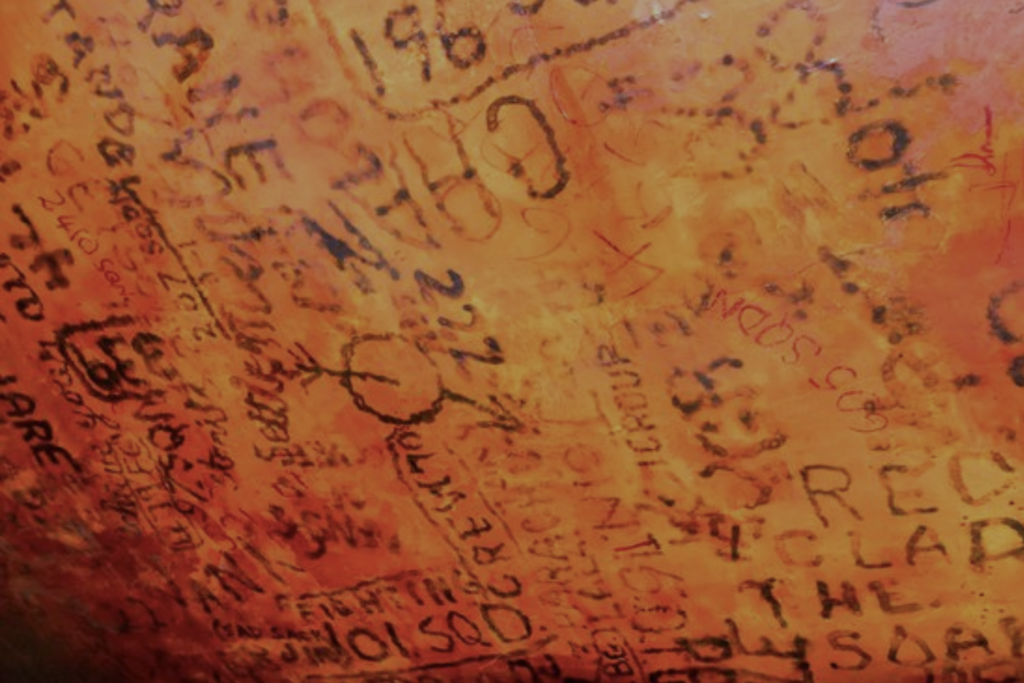

You can’t help but look up. The ceiling is covered with decades-old graffiti. It is not the profanity or pop art so often seen today on buildings, fences, and other public and private places. It’s not even the famous “Kilroy was here.” It is the names of aircraft, aircrew, and bomber units that were stationed nearby during the Second World War, along with dates of when some of the markings were made.

Except for a few aged aviators, perhaps enough for several aircrews, but certainly not enough to fill the combat box of a 12-plane B-17 formation, they are all gone now. They are part of history, part of a global conflict that claimed millions of lives from 1939 to 1945. But once they were young—some, very young. One American crewman, a waist gunner would write: “Less than two months after joining my Group, I became at age seventeen the oldest gunner in my squadron.”[1]

The graffiti is in The Eagle, a pub in Cambridge, England dating to the mid-17th century (and the previous inn on the site to the 14th century). It was in this comfortable and popular spot in February 1953 that Francis Crick and James Watson made their first public announcement of the discovery of the structure of DNA—“We have discovered the secret of life.” But that was postwar England, academic and scientific Cambridge, and a decade after boisterous young aviators left their marks—not to the secret of life, but certainly to the love of it.

They were Royal Air Force and American airmen of the United States Army Eighth Air Force. The former were likely flying Avro Lancaster British heavy bombers, “Lancs.” The latter flying Boeing B-17s, known as the “Flying Fortress,” and by those who flew in them as “Forts.” The bases were nearby and Cambridge, a “liberty town,” offered those with 48-hour passes diversion from the tedium of “mission counts” and the terror of acquiring the numbers needed to rotate home or elsewhere. Twenty-five sorties was the magic number. In 1943, the odds of completing them was remote—about 30%. Later, as fighter aircraft escorts improved in their range and capability, the number of required sorties rose 35—good reason to enjoy the company of others at the pub. Using candles and petrol lighters (cigarette lighters), probably Zippos, they stood on chairs and tables to leave their marks. When next they flew, it would not be unusual for less than half of the planes to return after the mission.

The “bomber war” was controversial then and remains so today. Ethics and war both entail necessary but difficult decisions. Randall Jarrell’s brief and vivid poem “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” remains a reminder of what the bomber crews faced on every mission. Though some missions were called a “milk run,” meaning little, if any enemy opposition, there were no guarantees. But for the young men returning from a mission and frequenting a pub, there was respite from their duties.

Whether on cave walls, brick walls, trench timbers, or the weapons and munitions of war, there has never been a shortage of war graffiti. Sometimes humorous, sometimes serious, frequently raw and emotional, the brief and often-hurried scribbles of warriors provide an interesting study in the psychology, sociology, and archaeology of war.

“Graffiti” and its singular form, “graffito” is derived from Italian “graffiato,” meaning “scratched.” It was a term coined in 1851 by archaeologists to describe inscriptions they found carved into the walls of ancient Pompeii. Many ancient sites have graffiti, so it is not surprising to find war graffiti among the ruins of battle sites. One need not look to lengthy ancient epics such as the Iliad or the Ramayana to consider either the emotions of warriors in war or the statements about them. War memoirs are carefully written with time and refection—war graffiti is hastily scribbled with adrenaline, boredom, and exhaustion.

Each graffito on the pub’s ceiling represents a story. Many of the marks are aircraft numbers such as “46455,” likely a reference to B-17 serial number 42-46455—a bomber that flew 58 missions, survived the war, and was later scrapped along with hundreds of others. However, it’s not all numbers. There is the Latin phrase “Alis Nocturnus”—On the Wings of the Night.” It was the motto of 58 Squadron, Royal Air Force—a bomber squadron flying Whitney bombers as part of Coastal Command. Another one reads “Bert’s Boys,” a reference to 196 Squadron, nicknamed for controversial Sir Arthur Harris who led Bomber Command. One of the boldest inscriptions reads “The Wild Hare,” the name of the B-17 bomber from nearby RAF Bassingbourn. It was lost on 26 November 1944 during a mission to Bremen, Germany—six of its crew were killed and the remaining four became prisoners of war.

Writing of a later American war, American-Vietnamese novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen observed: “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” His words resonate with those who study, experience, and remember the tragedy of war. Nearly two-and-a-half millennia ago, the famous epigram of Simonides was engraved on a stone placed on the Spartan burial mound at the site of the Battle of Thermopylae where the famous “300” Spartan warriors fell in 480 BCE:

“Go tell the Spartans, you who passeth by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.”

Consciously or subconsciously, perhaps that is what the young warriors were doing as they laughed, drank, sang, and reached for the ceiling at the Eagle pub—“leaving a mark”—longing to be remembered, even if only in graffiti.

As one looks at the ceiling it is easy to imagine the sights, sounds, and smells in the room from a bygone era. In a pub they lit the room with their candles and lighters. Returning to and in sight of their airfield, they lit the sky with double red flares—a signal to waiting ambulances that wounded crewmen were aboard. Thinking about the names, faces, images, and events represented on the cluttered ceiling, it is appropriate that they are found there and not on the walls. It was upward, in the flak-filled skies, where they flew and where many of them died.

[1] Cited in Kaplan and Smith, 19.

Recommended Reading:

Bratten, Jonathan. “The History Behind the Graffiti of War,” The New York Times Magazine (online), July 18, 2018.

Jablonski, Edward. Flying Fortress: The Illustrated Biography of the B-17s and the Men Who Flew Them. Corrected Edition. Brattleboro, VT: Echo Point Books & Media, 2014.

Kaplan, Philip and Rex Alan Smith. One Last Look: A Sentimental Journey to the Eighth Air Force Heavy Bomber Bases of World War II in England. New York: Cross River Press, 1983.

Nichol, John. Lancaster: The Forging of a Very British Legend. London: Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Overy, Richard. Bombers and the Bombed: The Allied Air War Over Europe 1940-1945. New York: Penguin Books, 2014.

Timothy J. Demy is a professor at the U.S. Naval War College (Newport, RI) and retired Navy chaplain. He is a graduate of the University of Cambridge with a master’s degree in international relations. Elsewhere, he earned doctorates in historical theology and also in the combined fields of technology and the humanities. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, he is an avid bibliophile, classical music lover, and student of piano.