By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

The Morgan Library and Museum – formerly known as Pierpont Morgan Library – on Madison Avenue has to be one of my favorite visits in New York City. A world-class collection of medieval manuscripts and related medieval relics is certainly known and appreciated, but there’s so much more than peerless medieval manuscripts here. J. Pierpont Morgan was a unique collector who amassed an amazing array of enviable collections. One needs at least a full day or two to take in just the always memorable exhibitions. When I was last there just last November (2021) the main exhibition was on manuscripts of the Morgan Library collection from 9th c. Carolingian to early Renaissance, but also included rare bejeweled Gospel covers from the Carolingian period all the way to Durer engravings. But there’s so much more – the gilded 12th c. Stavelot Triptych alone is worth the visit with its exquisite Mosan metal work and enameled rondels of the lives of Constantine and his mother Helena centered around a relic fragment of the “True Cross” (see above image). Of course, regarding wood fragments of the Cross, Voltaire famously quipped one could build a wood road from Paris to Berlin with all the reputed relic Cross fragments. Eusebius wrote a Life of Constantine that must be the source for the two side panel rondels, especially the dream of Constantine on the bottom left with the angel with the vision of the Cross before battle with Maxentius.

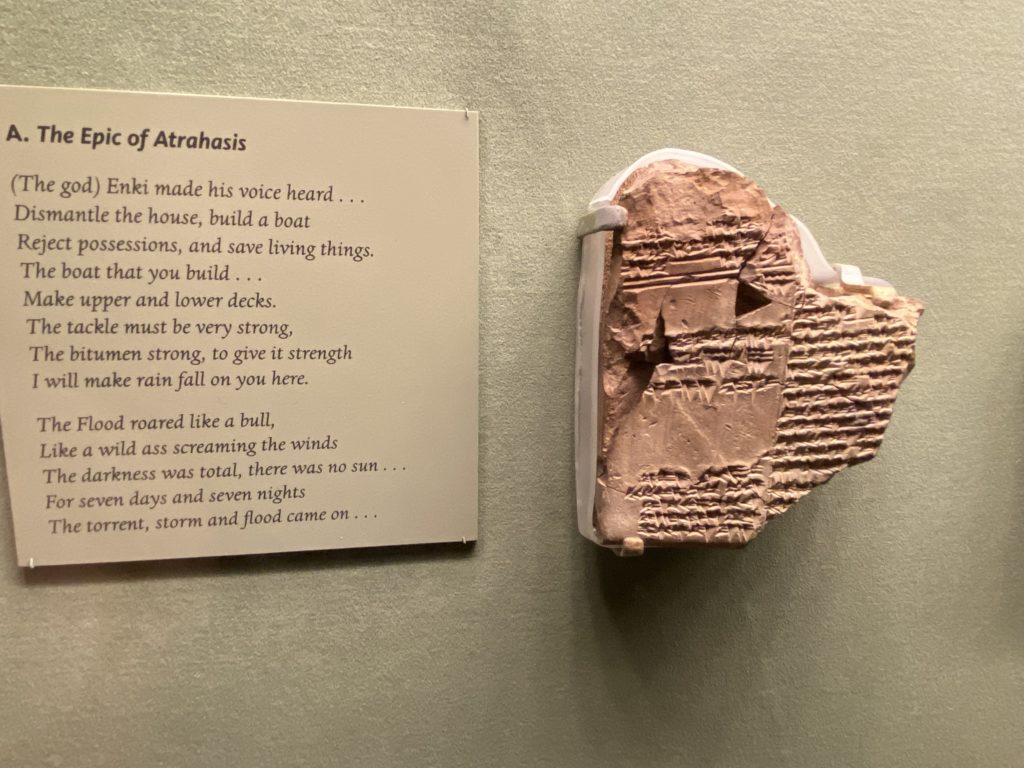

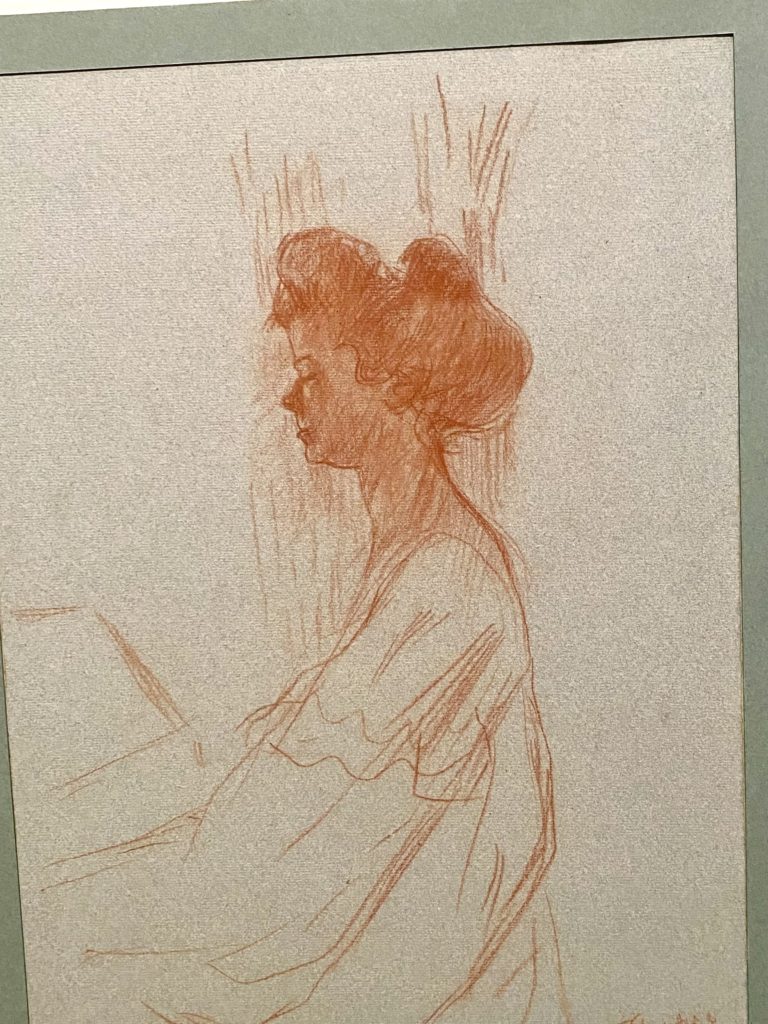

Among other incredible collections are a great assemblage of Mesopotamian cylinder seals and cuneiform tablets – including Babylonian lapis lazuli cylinders and a ceramic cuneiform tablet of the Babylonian Atrahasis Epic – and of course Etruscan bronze cistae and Roman material as well as Renaissance paintings, sculptures and glazed religious reliefs from the della Robbia Workshop in Florence. Not to be only a collection form antiquity, there are also exhibitions from more modern artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec sketches and even a collection of the French opera scores from the 18th century and in the Library a contemporary painting of Martin Luther and his wife. Other famous works include Tenniel’s illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice series, Giulio Clovio illuminations, works of Ingres and Gauguin, and Persian manuscripts of Rumi illustrations, among many others.

Durer has chosen the moment of John on Patmos receiving the command to take and eat the prophetic revelation from a mighty angel robed in a cloud with a face like the sun and whose legs like fiery pillars, one on land and on on sea, visualizing the text from Revelation 10.

Babylonian Atrahasis Epic cuneiform clay tablet, ca. Middle Bronze Age ca. 1626 BCE (Photo P. Hunt)

The Atrahasis Epic is also a Babylonian version of the Flood account – here written in Akkadian – recorded in Genesis and in other Mesopotamian tales such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, as Irving Finkel has so carefully recorded in his acclaimed book The Ark Before Noah. The most famous account is that from the Nineveh archive of Gilgamesh where Utnapishtim is commanded to built an ark sealed switch bitumen before the inundation but the Atrahasis story has equal details Finkel brings to light.

The della Robbia plaque was commissioned by a member the Antinori Family (Niccolo di Tommaso Antinori) and bears the Antinori heraldry in the blue and gold scudo below the scene. This plaque was pure tased by Morgan from Agnews in London in 1902.

Etruscan bronze cistae are often fantastic in inscribed decorations and the Morgan’s is from Praeneste (ancient Palestrina) discovered around 1864 and purchased by Morgan in 1907. It has a handled cover, also with beautifully-inscribed enigmatic myth scenes that have yet to be fully interpreted but likely connections to the Trojan War. This cista has bird-taloned feet at the bottom and chains along its cylinder side with ring attachments.

The humorous illuminations of this manuscript often have geese images, hence the name. This particular famous image shows a wolf and fox with likely bad intentions trying to teach a gaggle of geese how to sing from a musical folio on a lectern, but wolves and foxes may not be patient teachers when thinking about how tasty their pupils might be despite the present noise.

The date of this Neo-Babylonian lapis cylinder is roughly from the time of Nebuchadnezzar and shows the practicality of cylinder seals: how the circumference contains more images than can be seen at one time form the side. One altar looks like that of the moon good Sin, which was also the preferred god of Belshazzar, last ruler in Babylon in the 6th c. BCE, and the other may be the dog associated with the god of healing (Gula).

This Toulouse-Lautrec red chalk on blue paper sketch is actually a sketch of Misia Natanson. a talented pianist interpreter of Beethoven whom Toulouse-Lautrec had perform a particular Beethoven piece repeatedly for him, likely his 1811 “The Ruins of Athens” Opus 113 incidental music, as she relates in her autobiography. The most famous part of this music is a rollicking Turkish March that Beethoven also uses elsewhere, modulating back and forth between major and minor sections.

Whatever one’s aims in visiting the Morgan, it would be hard to imagine coming away in any way except with saturated satisfaction with the astonishing array of J.Pierpont Morgan’s collections – and ending after a visit to the gift shop with takeaways for any age. After a delicious croissant and latte, I purchased quite a few items including a pocket miniature treasure book on illuminated manuscripts and two fold-up children’s books for some lucky children.