By Susanne Houfek –

Unless you’re a medievalist you may not know Guillaume de Machaut was an important 14th century French poet and composer. Living from 1300-1377, he was prolific, innovative and influential, creating over 400 poems, 235 ballades, 76 rondeaux, 39 virelais and more, both secular and religious, in French and in Latin. His ars nova musical style is typical for France and Burgundy at this time. De Machaut was employed by various aristocrats and rulers around Europe. Of course, in intellectual France where composers, poets and artists are appreciated, he can be found on a 1977 French postage stamp of 1 franc 20 centimes.

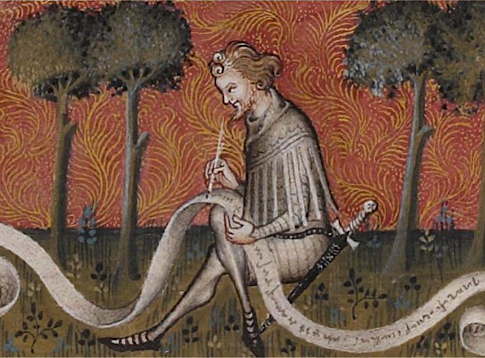

One of the most charming of his lyric-narrative poems is the courtly love poem, Le remède de fortune (The Cure for Ill Fortune), where the narrator, the author, falls in love with a lady, pursues her while overcoming obstacles, and learns how to properly court while growing as a lover, poet and composer. It is 4,200 lines long and includes seven songs. (In the courtly love tradition, courting a woman of higher status and professing undying love and loyalty through poetry make the man more noble.)

De Machaut supervised the creation of an elegantly illustrated manuscript for this poem, which required one artist and two collaborators, 1350 – 1355. The artist/illuminator, known as the Remède de Fortune Master, his name unknown, is the same one who illustrated The Miracle of the Leprous Pilgrim and St. Denis Aids Dagobert in the Missal of Saint-Denis, and The Life of St. Paul in the Bible Moralisée of Jean le Bon.

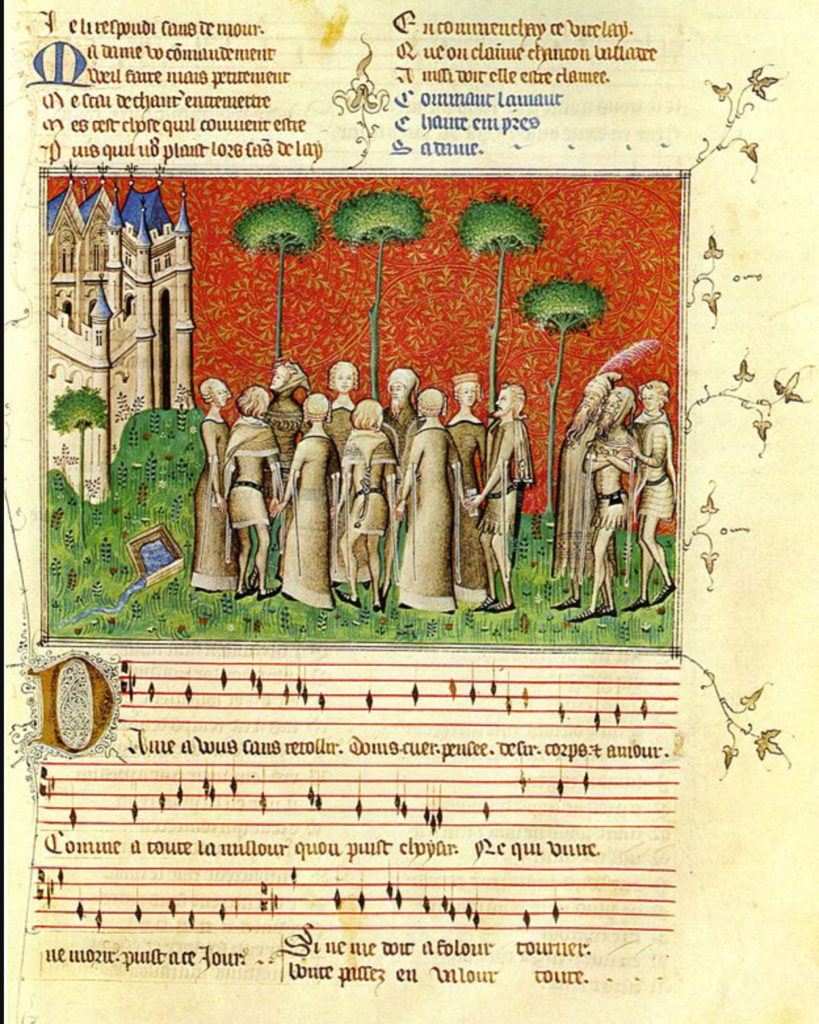

My favorite page from Le remède de fortune is fol. 51, “The Lover Sings as his Lady Dances.” How can you not find this entire endeavor endearing? The young suitor (with blonde hair, beard, with sword and cape) finds his lady (in pink pillbox hat) dancing a carole (circle-dance) with her friends near her castle. They are all holding hands. She invites him into the circle-dance, asks him to sing, and he obliges with a song called a virelai (or chanson baladée).

Machaut, Le remède de fortune fol. 51

But this folio offers so much more than charm. Title, stanza, image, decoration and music are integrated into one aesthetic unit. It operates on artful nested levels: the song within the poem that the narrator who is really the author composes , in the narrative, after the poem’s lady requests it, which he claims to make up on the spot. It’s spontaneous, but artifice. It claims to be humble, even naive, yet is highly sophisticated. It is innocent, yet dark. Song and dance are combined into one form. It relies on older forms of literature, yet introduces new forms of music. It provides understanding of social class mores, offers a sophisticated look at interpersonal relationships, and even functions as a form of therapy. And of course, this is an aristocrats-only world. The page invites its viewer to read, observe and listen simultaneously, then to respond with emotion, aesthetic pleasure and new understanding. It is art fully in the service of a life lesson and philosophy.

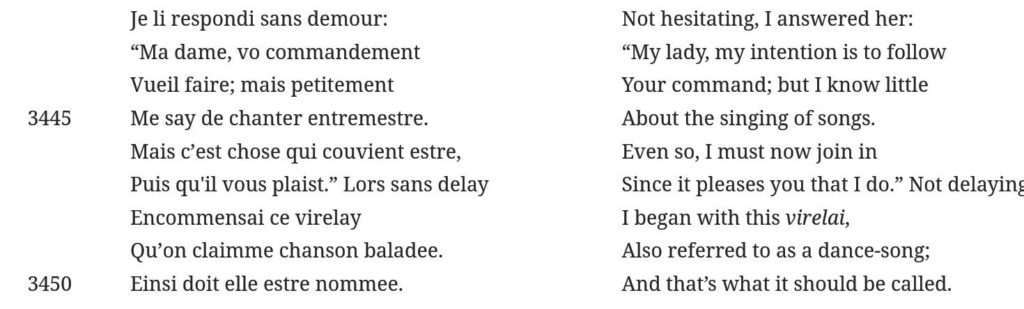

At the top are lines 3442 – 3450 of the poem, in red, followed by the title of the page, in blue. The large blue M is archaic uncial, for “Ma dame…” (“My lady…”) and has a very faint red tracery pattern in and around it. The letters of the lines of poetry are miniscule, with uncial capitals in the archaic form at the start of each. The red is dark, nearly brown, so likely made from cinnabar, a mercury sulfide ore mineral. You can see faint ruled lines. The Old French title is “Commant lament chante empress sa dame,” the ink derived from lapis or azurite. I was able to read enough of the text to locate this section of the poem and to figure out that the blue was the title, but it wasn’t easy!

Machaut, Le remède de fortune, fol. 51, lines 3442-50

In the center of the folio is a delicate and so-sweet depiction of the lovers’ encounter on a flower-strewn meadow. There are two scenes in one: the young man arrives with his two friends on the far right, then joins his lady in the dance while he sings. Her elongated castle has Romanesque arches and Gothic windows; crenellation along the top; the corner towers have blue witches-caps; and the steep blue roof lines are topped with fleur-de-lys that extend beyond the frame. The bright red background is adorned with gold-leaf homogeneous leaf and branch pattern. On the top and right of the frame are rinceaux – typical vegetal and floral margin decorations of 14th c. illuminations – here very delicate, simple, repeating stems with leaves and perhaps acorns or fleur-de-lys, along with tiny decorative squiggles; it appears these are all gold-leaf.

You can draw a line straight from the Remède Master to the Limbourg brothers — this ca. 1405 – 1408 Belles Heures illustration of the Duc de Berry and his entourage, with its Burgundian castles, green landscape, gold-foliated background and acorn/oak leaves or fleur-de-lys rinceaux.

Duc de Berry Belles Heures

In “The Lover Sings” (below image) I delight in how the Remède Master depicts in detail the fashions of the day, something he was known for: the man’s shawl with the long looped tassel, the jaunty hoods, the tall pink feather in the cap, the long single fringe dangling from sleeves, the girls’ elegantly styled hair. It interests me, too, that all his characters are blonde, as they are in much of early Italian Renaissance painting. I understand this tradition began with Petrarch, with his love poems to the curly-blonde Laura, and it became fashionable for Florentine women later to lighten their hair to blonde. Of course, every one of the Master’s characters here is handsome or beautiful.

Remède Master, “The Lover Sings” illumination

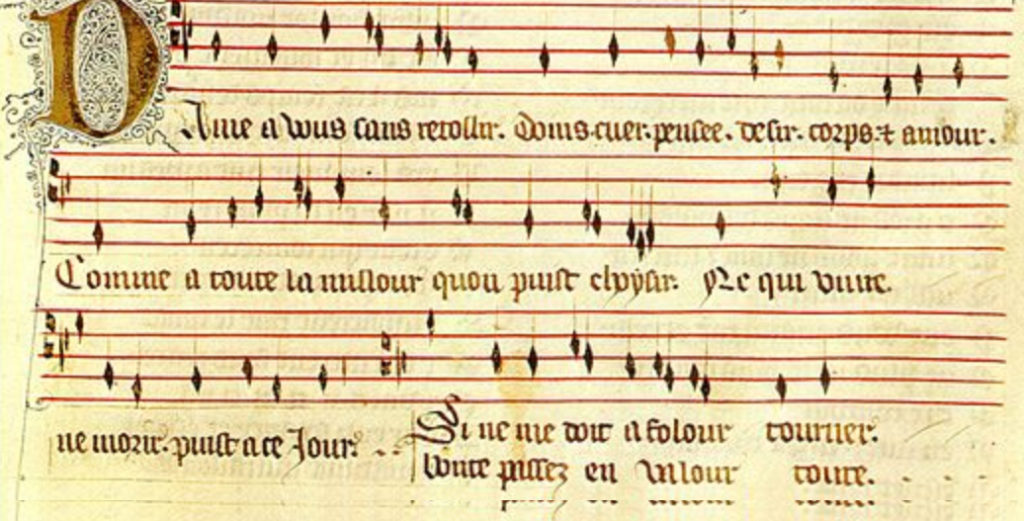

In the bottom third is “Dame, a vous sans retollir,” the virelai the suitor sings to his lady at her request, with score and lyrics for the refrain. It was composed by de Machaut. In fact, he created this new type of song, the virelai, which has a circular form – here, refrain, verse, refrain, verse, refrain, verse – and is monophonic.

The majuscule D, for Dame (below), looks like gold-leaf and features delicate tracery. Extending from the left side of the D are simple rinceaux — long vertical delicate curving lines. The lyrics are in miniscule, with each line beginning with archaic uncials. The elegantly twisted S near the bottom marks the beginning of the first verse. The music staff is five lines, a form which first appeared in Italy in the 13th c., and the notes are all the same shape, located farther or closer apart to indicate timing – closer ones are eighth notes – and there are no ligatures (a graphic connecting notes).

“Dame, a vous sans retollir” with majuscule D for Dame”

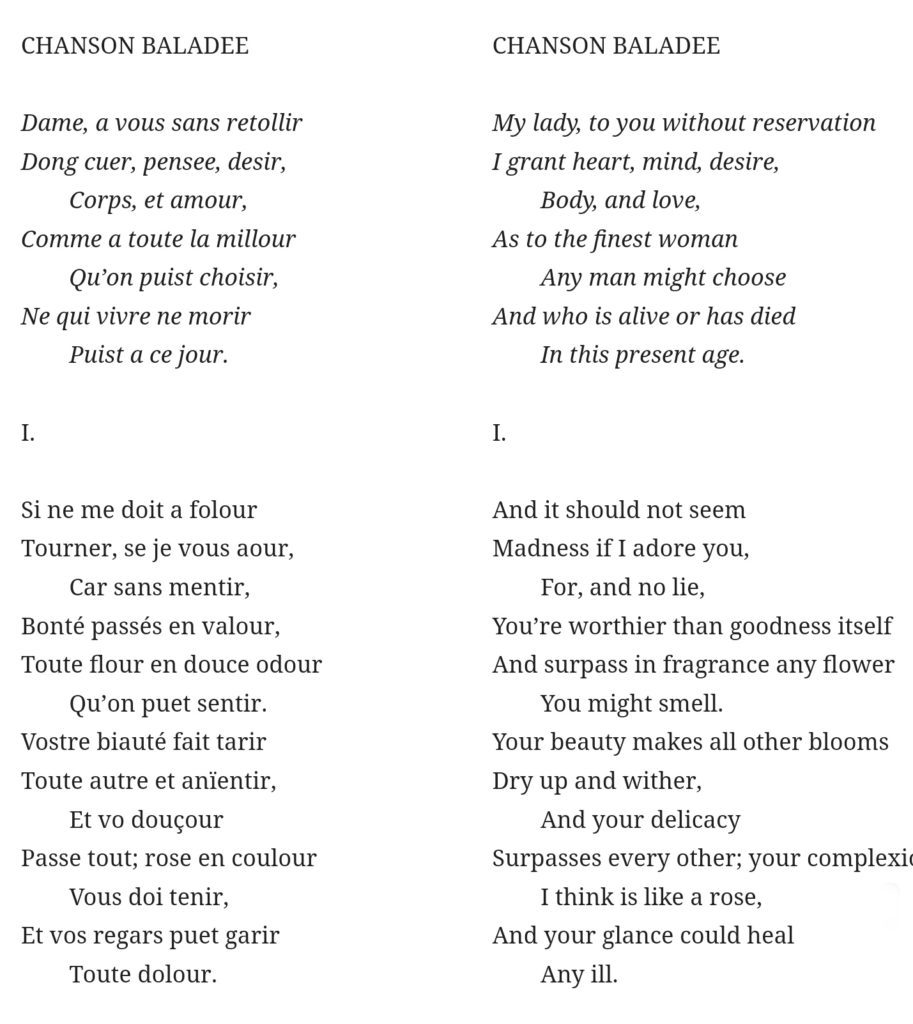

Here are the words to the refrain and the full first verse (of the three in total). Again, how utterly charming.

If you want to hear this virelai, here are links to an interpretation:

Dame, a vouz sans retollir – Guillaume de Machaut

(Links to an external site.

https://www.facebook.com/221171337161/videos/922960234830253

Ultimately, however, de Machaut’s poem is a cautionary and poignant tale. While the couple does exchange rings after the song and dance, at the end of the poem the lady seems to have lost interest, either hiding their love by pretending to be disinterested, or actually moving on. She says, “…qui en amour ne scet faindre, / il ne peut a grant joye ataindre” (“…a lover who does not know how to feign, cannot attain great joy”). The narrator, who can only hope she will ultimately return his love, learns that it is better to pay homage to “Love” than to a lady, that writing about love is more important than love itself. He accepts that hope and poetry are sufficient remedies for the ill fortune of suffering from desire. Sigh…I was really rooting for our young man.