P. F. Sommerfeldt –

Julius Caesar knew that to destroy the fractured Gauls, his overarching task was to accentuate their tribalism, not their national unity, in order to divide and conquer. History repeats this time and again as Michael Anderson cogently writes on tribalism, the bane of 21st century America. Anderson has done it again with a great sequel book to his Progressive Gene, which identifies deep emotional and even genetic tendencies and responses in behavioral psychology that drives and divides humans into compassionate (progressive) or loyal (conservative) camps, albeit along a broad spectrum. Tribalism is a long-held tenacity to cling to limited regional “us versus them” clannishness or limited nationalism over, for example, multiculturalism, global identity and seeing humanity at large. Racism, for example, is a political construct of the most superficial xenophobic tribalism.

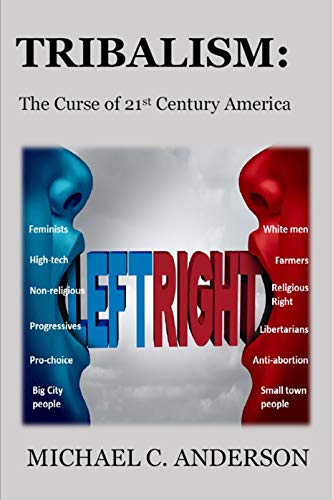

Anderson’s new book is Tribalism: The Curse of 21st Century America and it couldn’t be more timely as 2020 rages on. “Left versus Right” has become increasingly polarized, especially when the current Trump divisiveness becomes ever more entrenched against “libtard” Democrats like myself, such that honest conservatives despair along with honest liberals – each side with patriots who know national unity is becoming ever more elusive across the abyss. Who could have imagined that Republicans and Democrats could represent such horrible polarized “enemies” as Americans have somehow seemed to become? Weren’t we told only a generation ago that Soviet Communism was the enemy, not our own country’s political parties. Is the dichotomy between Republicans and Democrats as “enemies” true or merely propaganda? I believe the latter. Of course, the fault is on both sides, as Anderson documents.

Nativism and anti-immigration prejudices – nationalist xenophobias – are other aspects of the worst kind of tribalism that can be exploited by internal and external forces. Media preferences can all too easily reinforce tribalism, where charges of “fake news” add fuel to the already irrational flames. Too few know that the meme of “fake news” (part of dezinformatsiya) was a favorite device of Stalin’s NKVD (becoming the KGB) to discredit and destroy opposition and neutralize international media by sowing distrust, undermining what would be perceived as “true’ in postmodernist relativist understanding; in this country “fake news” didn’t really enter the common vocabulary until the political campaign of 2015. The more lies anyone can tell and get away with, the more bewildering the search for knowable truth becomes in the insidious aim to deceive public opinion. To international intelligence analysts, it is clear that certainly within the last decade or so Putin’s authoritarian apparatus exploits the possibilities for disinformation to the max, using the wiliest propaganda experts in pursuing much of this deliberate policy, knowing how to use tribalism in the worst possible ways to divide and destroy other sovereign nations. We should examine exactly how the media has become in Trump’s words, “the enemy of the people” because this rhetoric sounds exactly like what you would have heard and still hear coming out of Russia state-owned organs.

On the simplest level, most people who follow sports have favorite teams – usually their local ones – and this is a deeply-ingrained tribalism where individuals vicariously identify with a sports team that likely doesn’t even know that individual’s existence. I knew rabid fans who became so angry “their” team lost that they literally threw out the television from an upper apartment window in blind rage. Absurd, for sure, but an example of simple tribalism run awry.

Some of my favorite text sections in the book have to do with extended analyses of how we got to this current impasse through Enlightenment rationalism, to post-Enlightenment, Collectivism, Socialism and Liberalism to Postmodernism. Anderson also says (p. 206) about Trump: “He’s not even a Conservative. He’s a Populist and Populists are politicians who don’t embrace a particular ideology but build a platform around what they think the people want.” Great graphs like on p. 207 show how educated people have gradually moved toward the Left – partly because of academic bias – and many credible political surveys right now confirm educated people moving toward Independent and Democrat affiliations and away from the Republican party as it has polarized so far away from the center and embraced authoritarianism in executive branch power. Elsewhere Anderson’s keen observations and possible solutions include building bridges between divided ways of thought that are exacerbated by enculcated academic and media philosophies to break down animosities to find common ground (p. 282): “If Americans could see their government functioning the way they believe it should, working for the benefit of all of us, the tension level would abate within the tribes. Unfortunately, this will not happen before the end of the Trump presidency. Successful or not, Trump is too divisive to get the Left talking to the Right.” Anderson doesn’t say it, but in my opinion Trump is the ultimate Tribalist.

This book offers insightful commentary and documentation, and is very clearly written with historic depth. Anderson shows that he can reach me, a Jewish liberal, right between the eyes and in the heart, not with deadly aim so to speak, but with genuine passion and warnings for the immediate future. Anderson may be a prophet in this regard. His glossary at the end is superb, and while he doesn’t mince words, it’s almost impossible to see him taking sides in partisanship. I simply cannot recommend this book enough for readers of modern political thought. Anderson’s warnings are on the mark. The alternatives are frightening, and civil war and dissolution of the U.S. could too easily ensue if we don’t quickly fix the problems of tribalism. When I last stood in the old Athenian Agora in 2016 and saw the ruins of the Bouleuterion, the Greek political voting chambers where democracy began, tears came to my eyes as I pondered how fragile democracy remains. This was even before Trump…