By Andrea Gáldy –

In sixteenth-century Florence, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici succeeded his murdered predecessor Alessandro in 1537 and, even though the murderer was a close relative, knew very well what he needed to do to stay alive and in office. He had inherited a guard staffed by Italians and headed by Pirro Colonna which may have been satisfactory in general but did not help Cosimo’s attempts to gain a direct line of report to the emperor.

As a youth, Cosimo had witnessed the allure of imperial “German” guards during Charles V’s coronation at Bologna in 1530. They must have made quite an impression and, as soon as he had become Duke of Florence, Cosimo seems to have nurtured a plan to exchange the old for a new bodyguard. There were several advantages: a German guard would be less annoying than one composed of Italian soldiers (Cosimo de’ Medici, 29 June 1541), it would also help to get rid of its irritating captain and, finally, it would give Cosimo more room to manoeuvre in a duchy of very limited sovereignty under the control of Charles’s Italian ministers. It was therefore important for him to bypass them and to get his way without causing offence where it mattered.

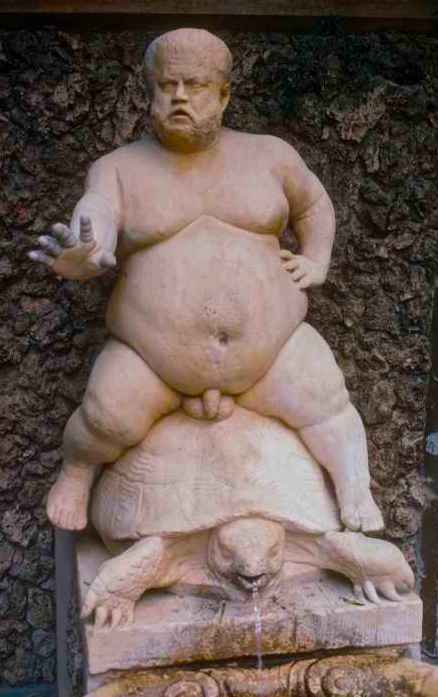

A pretext was found after Cosimo’s wedding to Eleonora of Toledo, daughter of the Viceroy of Naples Don Pedro of Toledo, and after the young couple’s move to the Palazzo della Signoria (Palazzo Vecchio) in 1540. Eleonora was a political animal and an inveterate gambler. Her court was populated by several dwarves (Fig. 1, Cat. 15) in accordance with Spanish and imperial fashions. In June 1541, the desired opportunity offered itself, when during a game of cards he was losing against Eleonora, Pirro started to beat one of the duchess’s protégés. At this point, Cosimo was “forced” to express his dismay at the lack of proper behaviour towards his wife, in particular since she and her family were closely connected to the Empire. Pirro was dismissed and a new guard based on the imperial model of Charles V’s “cien tudescos” was created.

Fig. 1, Valerio Cioli (1529-1599), Barbino the Dwarf, c.1564-66, marble, Giardino di Boboli, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.

Fig. 2, German workshop (Nuremberg?), Foot soldier’s cuirass worn by Johann Fernberger von Aur (1511–84), c.1580, steel, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna.

The current (unusual) exhibition at the Uffizi brings together a range of exhibits rarely seen in this combination at the gallery. True enough, as was usual in early modern Europe, there was an important Armoury near the Uffizi Tribuna, for which several rooms were set aside and especially decorated. The rooms still exist and so does the decoration. The suits of armour and weapons were taken away in the eighteenth century, often destroyed, and can only be reconstructed in part. The guard’s armoury was a different entity and therefore did not share the fate of the Medici armoury and a substantial portion of it is preserved in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello. One of the highlights of the exhibition (unfortunately not held in the rooms of the former Uffizi Armoury) is the freshly restored armour of the lanzi’s captain Johann Fernberger von Aur (c.1580; Fig. 2; Cat. 34), another consists of the (sparse) remains of Duke Cosimo’s set of armour (c.1538; Fig. 3; Cat. 30). When Titian painted the emperor’s (lost but preserved in a copy by Rubens) bearded portrait in armour after the battle of Pavia, this type of portraiture had become fashionable among members of the nobility connected to the Empire. For a small duchy such as Florence with new members of the European aristocracy at the helm, both the German guards and the type of portrait became an indispensable sign of allegiance (Fig. 4; Cat. 29).

Fig. 3 a; b; c and d, Innsbruck, Jörg Seusenhofer and Leonhard Meurl, Remains of Cosimo I’s light horse soldier’s cuirass (Parts of the cuirass belonging to Cosimo I, depicted in the numerous versions of the official portrait devised by Agnolo Bronzino), c. 1539, steel, Musei del Bargello, Florence.

Fig. 4, Workshop of Angolo Bronzino, Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in Armour, 1543-45, oil on panel, Galleria Palatina, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.

But there is not only armour to admire, e.g. the typical armour and weapons of members of the lanzi, even though much effort and progressive techniques went into their production. Rather the narrative of these trabanten (i.e. body guards) also comprises archival testimonials offering more than just a glimpse into the origins, duties, even family lives of the men employed by the duke and later grand dukes. Once one starts to search for them in the etchings, engravings and paintings of the time, it becomes clear how often they were portrayed together with their master. Where the (grand) duke appeared, he was surrounded by his guards; in fact they became a symbol of his rule. Several interesting pieces, i.e. paintings, etchings and engravings, in the exhibition make it clear how many of the lanzi were on duty during special occasions, such as coronations, festivities and pageants. In other depictions, we can see bodyguards half hidden behind doors, guarding a meeting etc.

For the two centuries the lanzi formed the Medici body guard in Florence, they were an important part of Florentine daily life. Their headquarters were in the Loggia dei Lanzi (hence the name) and in a building behind it with a door opening onto the loggia. The building fell victim to the Uffizi extension and its door was walled up after they ceased to serve the Medici. The lanzi also had their own church at Santo Stefano al Ponte Vecchio; in theory they had to be Catholics but, as so often during his rule, Cosimo turned a blind eye to confessional alliances as long as they caused no trouble in public. His sons were less tolerant. The “German” members of the lanzi came from “Alemagna”, an area roughly comprising Southern Germany, Austria, the Südtirol and therefore brought a rather diverse heritage with them to Florence. There, they integrated quite well with the native population, e.g. guards married into Florentine families, but as a large minority, they were still visible and maintained their own manner of prayer or their typical music, fashion, food and laws.

Fig. 5, Florentine workshop, “Tunic” from the court of Cosimo I, c.1560, plain crimson silk velvet, Museo di Palazzo Reale, Pisa.

Perhaps, surprisingly for this type of exhibition, women play an important part. The fates of the wives or widows of the guards and their children are an important issue here and can be traced by means of several documents, such as petitions, from the archive of the German guards, almost entirely preserved in the Archivio di Stato of Florence. Nonetheless, the main focus is on two aristocratic women that were enormously important for the destiny of the German guards: Eleonora of Toledo who played an important role in the pretext needed to create the lanzi. She is represented by her portrait as well as by a gown (c. 1560; Fig. 5, Cat. 14&Cristofano di Papi (c.1530-1605), Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo, c.1549, oil on panel, Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Museo della Moda e del Costume, inv. 1890, n. 1469, Cats. 20) preserved to this day because of its use as the garment of a statue of the Madonna Annunciata a San Matteo. About two centuries later, Anna Maria Luisa (Fig. 6; Cat. 77), sister to the last Medici grand duke Gian Gastone, was the last to preserve a nucleus of the German lanzi for her own protection after the Guards’ abolition while waiting for the arrival of the Swiss Guard of the new ruling house of Lorraine. The Florentine Medici men may have thought the lanzi were theirs, but two powerful Medici women, i.e. Eleonora as a foreign dynastic bride and Anna Maria Luisa as the last Medici, were important players at the beginning and end of their history.

Fig. 6, Antonio Franchi, Portrait of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667-1743), 1689, oil on canvas, Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Depositi delle Gallerie, inv. 1890, n. 2738.

Both the exhibition and the catalogue are highly to be recommended; it is rather a shame though that the catalogue is only available in Italian.

Cento lanzi per il Principe curated by Maurizio Arfaioli, Pasquale Focarile and Marco Merlo.

Uffizi, Sale di Levante, first floor

4 June – 29 September 2019, open Wednesday to Sunday, 8.15 to 18.05 and Tuesday 8.15 to 21.05, closed Mondays

Maurizio Arfaioli, Pasquale Focarile and Marco Merlo, eds. Omaggio a Cosimo I: Cento Lanzi per il Principe. Florence: Giunti, 2019.