By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

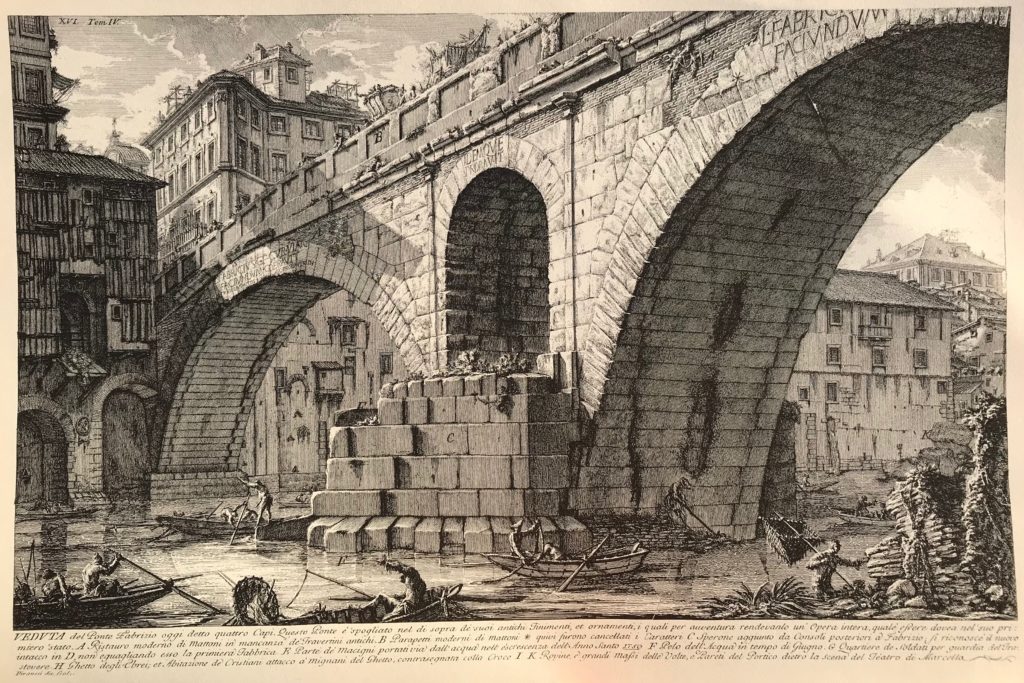

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-78) is well known as a Neoclassical engraver of Roman monuments and shadowed architectural fantasies (such as invented or imaginary carcere or “prisons”). But his work as a pioneer in archaeology is not as familiar, although his work provides ample details about the state of Roman ruins and his own preservation and restoration conducted from his stone and plaster workshop in Rome on the Via del Corso. While he was keenly interested in understanding antiquity purely on his own from his architectural training, it is also highly likely that antiquarian collectors of Rome – especially British visitors connected to Gavin Hamilton – while on the early Grand Tour stimulated some of Piranesi’s commercial restoration work and bought his exquisitely detailed engravings of Roman views.

Born in the Veneto near Treviso just north of Venice – home of prosecco – Piranesi’s father was a stoneworker and mason who passed on quite a bit of his craft to his son; a brother also aided him in his education, including Latin tutoring. This combination of craft and scholarship would naturally be a magnet to the ruins of Ancient Rome as they precariously survived in various monuments and fragments spread around the Eternal City. An early apprenticeship to his uncle, architect and engineer Matteo Lucchesi (1705-76), who was part of Rome’s Magistracy of Waterworks (Magistrate delle Acque) and had studied Palladian architecture, gave Piranesi the perfect training to undertake historical studies from an engineer’s perspective as the magistracy worked on building restoration from the technical side. [1]

Piranesi also worked from 1740 onward as a draftsman for the Venetian Ambassador to the Papal Court of Benedict XIV. Marco Foscarini, the Ambassador allowed Piranesi to live in the Palazzo Venezia on the Via del Plebescito in Rome just north of the Capitoline Hill, where he learned etching and engraving from artist Giuseppe Vasi (1710-82).

Piranesi carefully documented views (Vedute) of Rome in several architectural books, Prima parte di Architectura e Prospettive in 1743 and Varie vedette di Roma Antica e Moderna in 1745. But Piranesi had returned to the Veneto and Venice in particular in 1743 where he became close to artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who apparently taught him much about dramatic architectural and topographic perspectives. Piranesi’s “Skeletons” circa 1748, from Grotteschi (Grotesques), even directly quote Tiepolo’s Scherzi in elements like Tiepolo’s leering herms.[2]

Although some of his identifications of Roman buildings such as the Temple of Cybele have now been corrected (now known since the 19th c. as the Temple of Hercules Victor in the Forum Boarium), his visual recording is more accurate than Andrea Palladio’s visuals of around 1580. [3]

Piranesi not only improved on many of Andrea Palladio’s measurements of monuments, one of his most important contributions, he also ultimately published exceptionally architecturally accurate views of Rome in his Le Antichita Romane de’ tempo della prima Repubblica e dei primi imperatori of the 1750’s and his Campo Marzio dell’antica Roma of 1762. Piranesi was elected to the Accademia di San Luca, the artists’ guild, in 1761 and also began publishing form his own printing press in Rome from the Via Corso. Based on service to the Papal States, Piranesi was “knighted” as a Cavaliere of the Golden Spur in 1767. Because visiting British antiquarians often sought him out for his accuracy and working knowledge of Rome displayed in tours and in copious notes on technical drafts as well as for his vedute series, Piranesi was elected in 1757 to the London Society of Antiquaries as an Honorary Fellow.[4] He had also worked closely with the Scottish antiquarian, Neoclassical artist and pioneering nascent “archaeologist” Gavin Hamilton (1723-88) when Hamilton excavated – not always scientifically – for buried Roman sculptures and monuments, especially the first excavations of Emperor Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli (1769-71) and the Roman ancient port of Ostia Antica (1774-5). Due to his training in engineering and architecture, it is likely that Piranesi was more interested in recording details and contexts than Hamilton, himself more reputable than most contemporary antiquarian dealers. Many of Hamilton’s finds are centerpieces of collections in the Museo Pio Clementino of the Vatican as well as the British Museum in London. [5] Piranesi also restored the famous marble Piranesi Vase – adding and even carving extraneous elements – now in the British Museum Enlightenment Gallery.

One of Piranesi’s important offices since the mid-1750’s had been his connection to the new Portici Museum adjoining the Palazzo Reale of the enlightened King Charles II of Naples (1716-88), where Piranesi was much involved in sorting and likely drawing the new Roman archaeological finds from Herculaneum. Because at least a third of the monuments Piranesi carefully engraved are now lost or destroyed, his visual records – carefully annotated in over a thousand meticulous copper engravings [6] – still faithfully serve as the best contemporary sources for what had survived in Rome to his day.

Notes:

[1] J. Wilton-Ely. The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

[2] “Piranesi’s The Skeletons, from Groteschi (Grotesques), ca. 1748.” Metropolitan Museum of New York (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/361994).

[3] Calder Loth. “Can We Trust Palladio? Antoine Desgodetz Details Palladio’s Inaccuracies” Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, June 4 2014 (https://www.classicist.org/articles/can-we-trust-palladio-antoine-desgodetz-details-palladios-inaccuracies/)

[4] Darran Anderson. “Pen Portraits: Giovanni Battista Piranesi”. The Architectural Review, July 2, 2018.

[5] David Irwin. “Gavin Hamilton: Archaeologist, Painter, Dealer.” The Art Bulletin 44.2 (1962) 87-102.

[6] Anderson, 2018. “Piranesi remains a valuable guide, forever etching the places that cannot be photographed.”