By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Thomas Kren with Jill Burke and Stephen J. Campbell (eds.), The Renaissance Nude, Getty Publications: Los Angeles 2018.

The Renaissance Nude, The Royal Academy of the Arts, London, 3 March to 2 June 2019, organised by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Royal Academy of the Arts

The current Royal Academy (RA) exhibition The Renaissance Nude investigates the representation of the nude human body from the fourteenth century onwards. While during Greek and Roman antiquity human nudity seems to have been commonplace, at least in the arts, during the middle ages the nude body was no longer used as a form of physical celebration. Although it did not disappear completely, it rather served the celebration of the steadfast faith of saints and martyrs. Saints chastising the flesh and mortifying their bodies, e.g. St. Jerome, as well as martyrs undergoing terrible forms of martyrdom, e.g. St. Sebastian (Bronzino, Fig. 2), were customarily depicted as lightly clad or in the nude.

What changed over the centuries was the modelling of such representations after ancient gods and heroes and the increasing life-likeness of these works of art. Still, they were made for the display in churches and chapels as well as in magnificent books of hours such as the one for the Duke of Berry. And, what was perceived as too much nudity would caused a stir well into the sixteenth century, when for example Michelangelo’s David and even more his Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel called forth debate that ended with the famous fresco in Rome being partially overpainted with drapery in accordance with counterreformation tenets.

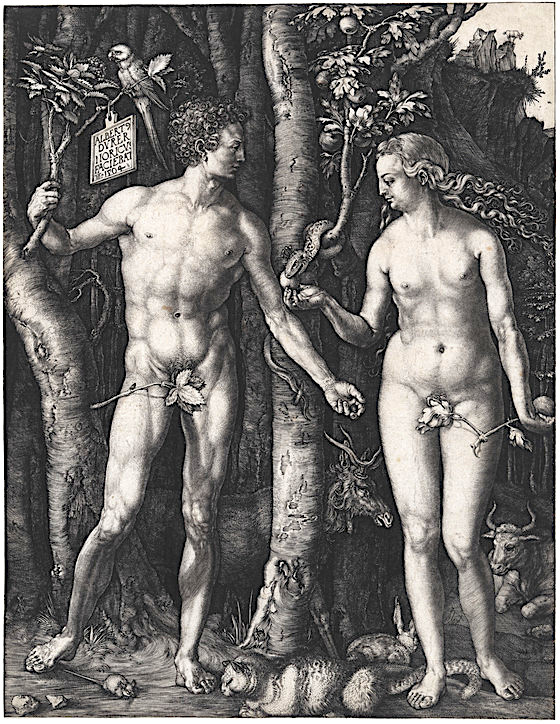

Old- and New-Testamentarian figures, from Adam and Eve (Dürer, Fig. 3) to the Blessed Virgin with the Christ child and the Passion of Christ provided the subject matter for depictions on walls, reliefs, panels, pages and in sculpture. Until the fifteenth century, the artistic style and taste conformed to “regional” ideas of beauty that bore little relation to ancient models or realism. Nonetheless, for example in the case of the Netherlandish Limbourg brothers working for the Duke de Berry, such depictions were able convincingly to express sensuality and to present religious narratives. Regionality is also a keyword in relation to puzzling fashions south and north of the Alps and to an understanding of modesty that would bare particular parts of the body, while leaving the head and face covered, e.g. in sixteenth-century Venice. After all, such nudity could be partial – although no less startling – and nevertheless be perceived as dangerous.

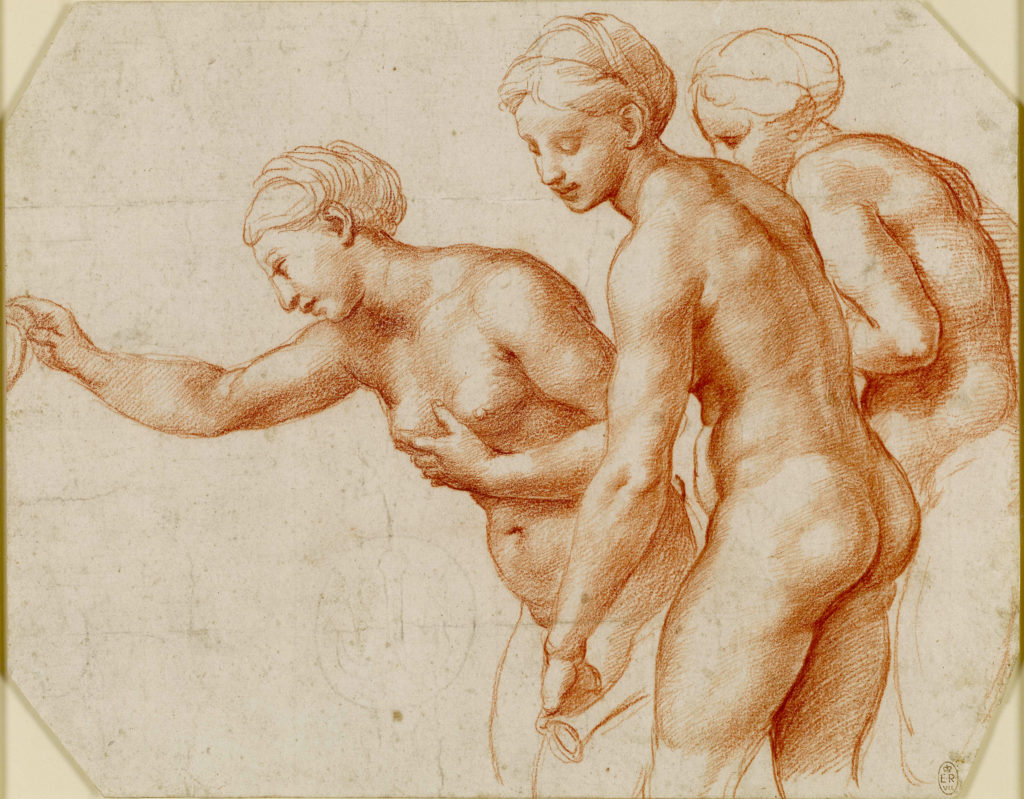

With the advent of “The Renaissance”, however, classical antiquity started to play an ever greater role as information about ancient art and culture grew and spread. Particular works of art, such as the nude Belvedere Torso or the Spinario and types such as that of a Venus Pudica or Anadyomene (Titian, Fig. 4) could be adopted as models for secular and sacred art alike. A considerable portion of the exhibition is therefore dedicated to the issue of renaissance art and its stylistic and pictorial roots in antiquity. The use of all’antica works of art in the form of paintings, murals, drawings, tapestries, bronzes and book illuminations is being discussed. Ancient myths served as subject matters and followed the antique mode in their structure, rendering and look, frequently translating a work from one original genre into the next or from the Pagan into the Christian and/or vice versa, as in the fluid case of the Three Graces (Raphael, Fig. 1). Reduced-size formats in the case of statuettes and book illuminations made such works of art particularly appealing to collectors who would display them in their study rooms. A particular example discussed in the exhibition is the study of Isabella d’Este at Mantua, which housed many ancient and antique objects together with Christian works of art in a display context fashionable by the fifteenth century and adopted by male and female patrons of means and taste. Isabella certainly was an exceptional collector and patron in comparison with her male as well as female fellow enthusiasts. The juxtaposition of works with Pagan and Christian subject matters, many of them depicted in the nude, may have struck contemporaries as weird and unbecoming for a woman. Her familial background, however, including the patronage of her female relatives, had prepared her for this type of cultural diversity uniting the Christian and ancient worlds typical of humanist culture.

The Royal Academy show concentrates on a wide range of topics, including “The Nude and Christian Art”, “Humanism and the Expansion of Secular Themes”, “Artistic Theory and Practice”, “Beyond the Ideal Nude” and “Personalising the Nude”. It is a great strength of the exhibition that it not only compares ancient myths with Christian legends, southern with northern art and diverse uses and contexts across possible genres. It would have been easy to limit the display (and the excellent catalogue) to the artistic contrast between (and imitation of) the antique, mediaeval and renaissance rendering of human nudity.

The particular interest of the exhibition lies, however, in the added discussion of theory and study of the human body as well as of divergent renderings that, however, often use the same models as their more conventional counterparts.

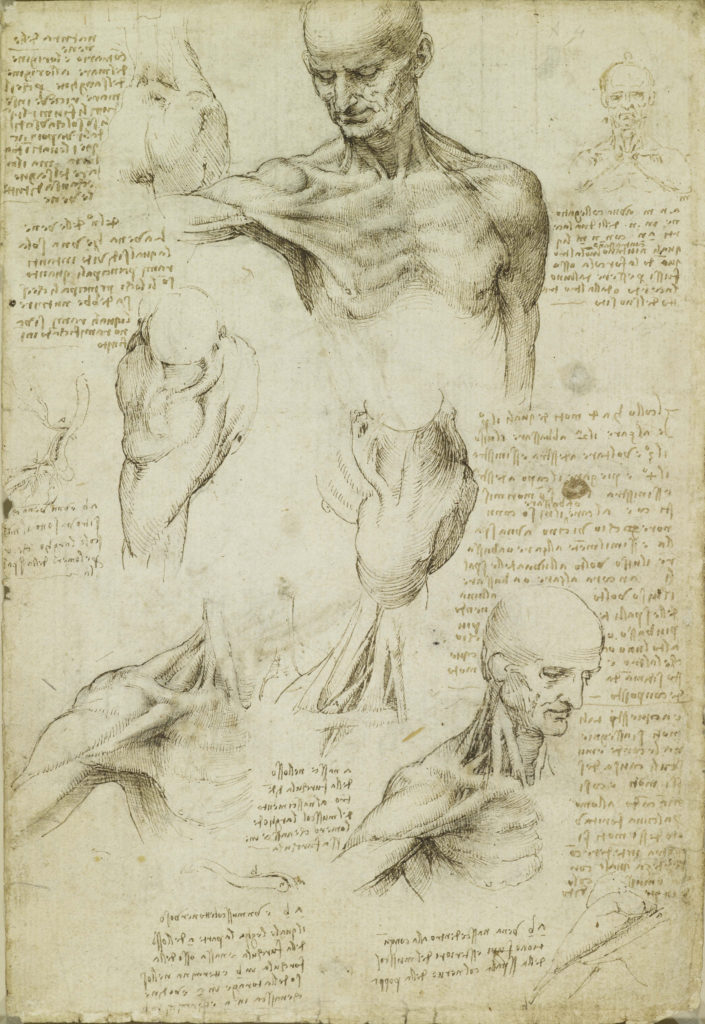

Perhaps the most interesting section is indeed the one on the theoretical investigation of the human body. At a time, when anatomical studies blossomed, albeit hidden away from the authorities, artists such as Isabella’s protégé Leonardo started to explore not just the beautiful nudity outside but also the workings of muscles and tendons inside (Leonardo, Fig. 5). Beauty became a matter of proportion and mathematics almost as if human bodies needed to be constructed in the way of architecture.

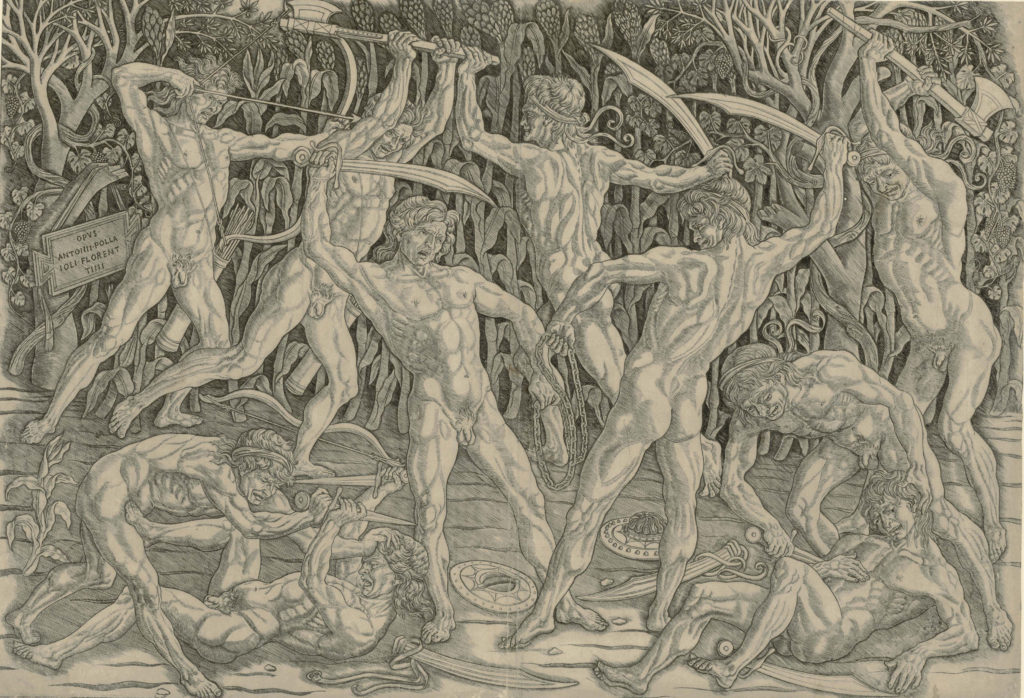

At this point, the all’antica grace of earlier Renaissance works of art (Pollaiuolo, Fig. 6) started to give way to a more academic treatment of the human nude that still regarded ancient art as its direct model but nonetheless harked back to an imaginary antiquity mainly useful for allegorical paintings (Dossi, Fig. 7).

The exhibition brings together a great profusion and diversity of themes; it is of great quality and interest, while the catalogue provides a welcome opportunity to revisit the exhibition and its narrative in one’s mind. If one looks for anything to criticise, one ought to mention the mass of exhibits in relation to the available room (and the considerable number of visitors, much to be applauded) which occasionally makes viewing a bit of a challenge.

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/the-renaissance-nude