By Andrea M. Gáldy –

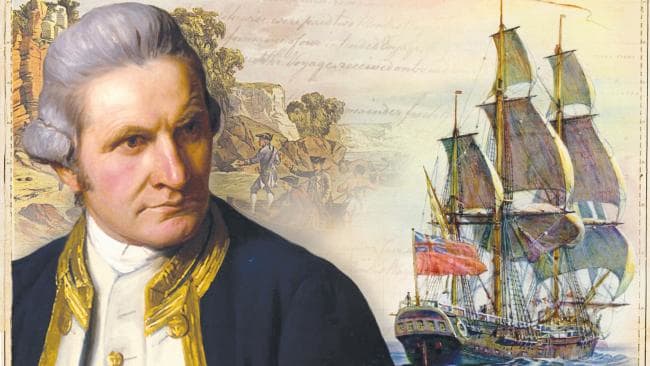

When Captain James Cook left for the first of his three expeditions to the Pacific in 1768, he stood in a long line of naval explorers looking for new routes and continents. His ship was appropriately named Endeavour and the task ahead was daunting.

Cook was a talented surveyor, as he had shown during previous journeys to Newfoundland, and perhaps this work had recommended him for scientific travels to the South Sea. He was meant to observe the Venus transit across the Sun with the aim to calculate the Sun’s distance from Earth. In addition, the Admiralty charged him with looking for the fabled continent of Terra Australis, the existence of which had been suspected but never been proven since antiquity. From the seventeenth century, Dutch explorers and the Dutch East India Company had been active in the Pacific area without being able to claim such a discovery. Now a British explorer in the company of British natural scientists was going to try.

Cook discovered Australia, at the time called “New Holland” to match “New Zealand” and Batavia, as well as a great many islands. He also managed to open this new world to the natural sciences, since eminent botanists, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, accompanied him and were able to make important observations as well as to take home botanical specimens for further study. Cook’s explorations not only brought him in contact with new species of fauna and flora, he and his crew also encountered native peoples settled in Australia and on the islands of “Oceania” for some (tens of) thousands of years.

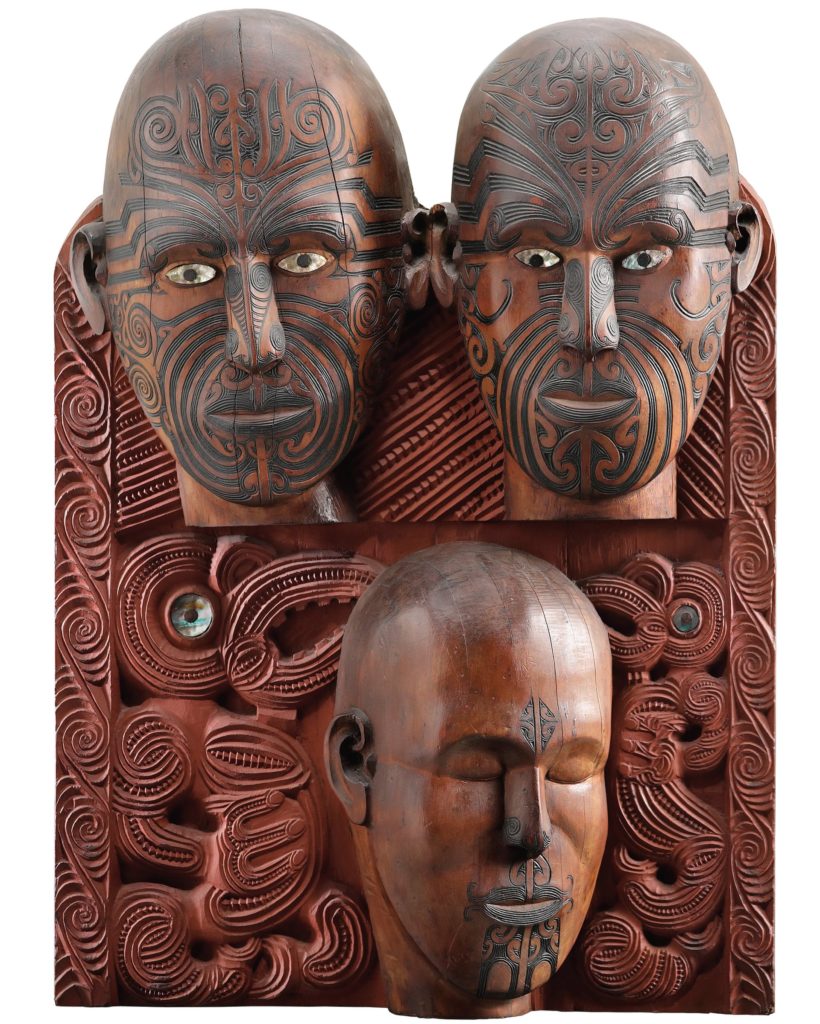

For both parties, for the English and for the diverse “indigenous” people, the ocean had been the path to carry them towards new places of trade and settlement. Both groups brought their own cultures with them and allow them to clash on the occasion of their meeting. Gifts were liberally exchanged, as well as infectious diseases, since for a while at least the Pacific populations seem to have expected that engaging with the new arrivals on equal terms might bring advantages. Many such presents were taken home to England and now form some of the most splendid exhibits currently shown at the Royal Academy, e.g. the feather form of a Hawaiian deity offered to Cook in 1779 (see above image). After a while though, these encounters turned sour on both sides and indeed Cook fell victim to a counter-assault when trying to kidnap the Hawaiian king KalaniÊ»ÅpuÊ»u, and was killed there (note the below image of his statue in Waimea, Kauai, Hawaii). This kind of image of a feathered cloak as a deity symbol looked foreign and primitive to the Europeans but carried notions of tremendous spiritual value and importance to the donors.

The Oceania show at the Royal Academy displays 200 pieces from the South Seas to give an impression of the rich and diverse culture the Pacific peoples had developed over the centuries. An important aspect of the exhibition lies in the presentation of the intentions of both parties in the eighteenth century and of the resulting misunderstandings and misinterpretations. For the peoples of the Pacific areas ancestor worship and the acknowledgement of what they call “mana”, the spiritual strength and charisma of a leader. Nonetheless, the show not only dwells on the past but also includes features of a present, in which the encounter between the “modern” West and a “traditional” Oceania continues and raises serious issues. For spectators not very familiar with Pacific culture and artifacts, confronting Oceanic heritage and the history connected to it constitutes a vicarious brush between explorers of earlier centuries, such as Cook, and the civilisation of the original settlers.

Even those who not necessarily subscribe to the notion of a general “white person’s guilt” will find it difficult to deny the grave loss of cultural and religious heritage the islanders underwent. Although they were at least in part willing to give up or modify their traditions, in the long run the encounter only brought financial, territorial and scientific advantages to one party.

Nevertheless, Pacific culture is by no means dead. Instead it is still of immense importance for the native peoples themselves who may use the Oceania exhibition to reach back and catch up with their own family and ethnical history.

The audience was notified that visitors from the Pacific Islands may be paying their respects rather than simply look at the artefacts and that their purpose is to be acknowledged. It is one of many levels, at which the encounter has turned into a discourse. These days, contemporary Pacific artists engage with Western culture by creating objects, for example Michael Parekowhai’s red piano He KÅrero PūrÄkau mÅ te Awanui o te Motu: Story of a New Zealand River (2011), both musical instrument and sculpture (see image below) or the panoramic video In Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015–17) by Lisa Reihana.

in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17 (detail)

Single-channel video, Ultra HD, colour, 7.1 sound, 64 minutes

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o TÄmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2014.

Additional support from Creative New Zealand and NZ at Venice Patrons and Partners

(c) Image courtesy of the artist and ARTPROJECTS

The cultural and artistic exchange goes both ways: both Henry Moore and Picasso were great admirers of Oceanic art, e.g. the sculpture of a Polynesia deity from island of Rurutu, the startling modernity of which made a lasting impression on them. And, after all, the idea of art as a means to convey religious believes is something Islanders and Westerners can easily share. Apropos of Capt. James Cook and his brave but possibly unwise demise in Hawaii trying to kidnap a Hawaiian king on Kauai, note below the wooden statue of Ku, Hawaiian God of War, from this wide-ranging Royal Academy Exhibition, the first of its kind to being together the heritage of vast Oceania.

Oceania, curated by Prof. Nicholas Thomas FBA and Dr Peter Brunt with Dr. Adrian Locke, 29 September ‘ 10 December 2018, daily 10am – 6pm, Friday 10am – 10pm, main Galleries, Burlington House, Royal Academy of Arts, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/oceania#articles-and-videos.