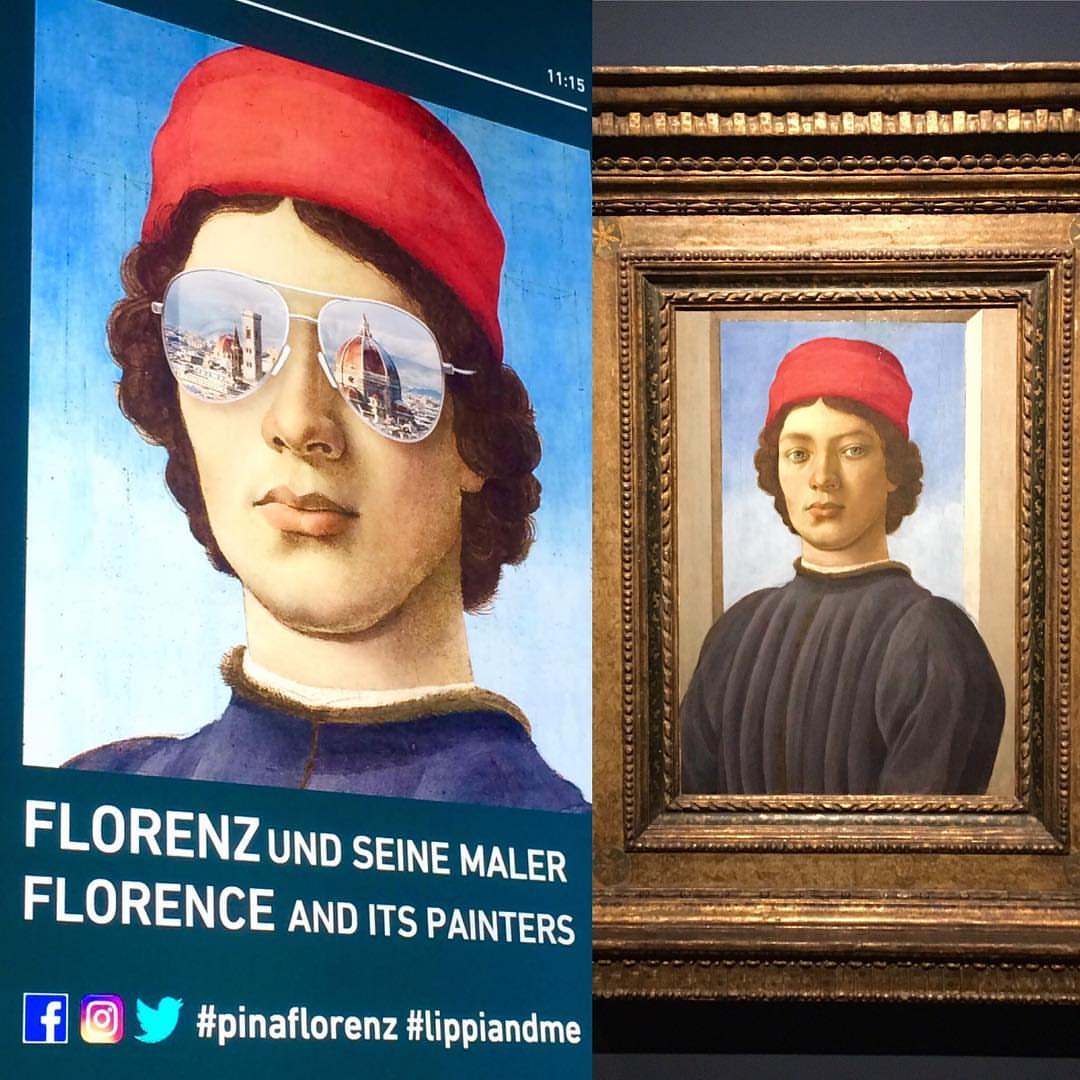

Fig. 1 Filippo Lippi, Portrait of a Young Man, ca 1480-5, National Gallery, Washington DC, Andrew Mellon Collection (image courtesy National Gallery of Art)

By Andrea M. Gáldy –

If it would not look so catty, temptation would be great to call the exhibition poster based on Filippino Lippi’s above Portrait of a young Man (c.1480-1485) the best thing of the current show ( (“Florence and its Painters”) on Florentine art in Munich’s Alte Pinakothek. The young man in question (Fig. 1 above) looks stylish and rather full of himself; he might turn round and dash off to the nearest fashionable bar for his daily prosecchino and a chat with his friends. We have all seen the type in cities of a certain life-style such as Florence, Milan or Munich. On the poster, this young man wears a pair of up-to-date mirrored sunglasses which reflect the cityscape of downtown Florence. Thus the advertisement makes an important statement: Florence as the renaissance city of artistic innovation was peopled by men and women like you and me. We are as Florentine as the quattrocento patrons, audience and creators of Florentine art.

Such a statement is important, since the profusion of early modern Italian art in the world’s museums and in the current exhibition at Munich makes it easy to forget that the paintsings, drawings and works of sculpture we admired were once commissioned an executed for and by real people. They served a particular purpose – often as devotional images or to commemorate family members – and originally were displayed within a particular architectural framework. The setting has often been lost or destroyed since the “modernisation” taking place during the Cinquecento and in later times. Encountering them in museums rather than churches, chapels or the private chambers of (Florentine) palazzi, takes away from their meaning to and importance for their patrons.

Fig. 2 Munich Alte Pinakothek “Florence and Its Painters” Exhibition (image courtesy of Haydar Korupinar for Deutschhe Welle, dw.com)

The Munich exhibition, slightly misnamed for we get to see the works of painters, sculptors and draughtsmen, creates an intimate space (Fig. 2 above) to help us look at the over 120 exhibits gathered, for example from Berlin, Paris, London and Washington. Several paintings belong to the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, of which Raffaellino del Garbo’s Lamentation (ca. 1495) was restored for the show and provides a vivid glimpse at the amount of grime collected over half a millennium and the benefits of modern cleaning methods (Fig. 3 below).

Fig. 3 Rafaellino del Garbo, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, ca. 1495, Bavarian State Art Collection (image courtesy of Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen)

The themes of the exhibition include sections on disegno, artistic innovation, on devotional paintings, including the much appreciated and often executed images of the Annunciation, on pictorial narratives and innovative sculptural works as well as on portraits and other types of secular painting. The particular focus is on artists of the later quattrocento such as Donatello, Ghiberti, Verrocchio and Botticelli, i.e., the top tier of Florentine renaissance production. A particularly interesting point, and welcome diversion from the more conventional topics of the show, is the presentation of technical aspects and of craftsmanship involved in creating these works, e.g. the transition from tempera to oil painting. In the case of panel paintings (Fig. 4 below) using the new oil technique it is important to note – and is explained – that it was not a Florentine invention but a northern, Netherlandish influence brought to Florence by means of Netherlandish works of art purchased and commissioned by Florentine bankers active internationally across Europe.

Fig. 4 Leonardo da Vinci, Madonna with Carnation, ca. 1475-78, oil on poplar panel, Munich Alte Pinakothek (image courtesy of Alte Pinakothek)

Altogether, the exhibition offers a well-considered array of wonderful art from an era and city proverbial for renaissance artistic production. The audience is captured from the start and the international group of art historians responsible for the explanations on site and for the catalogue chapters, available in English and German, provide much background information that manages to make up to some degree for the context the individual works of art have lost over the centuries. Particularly strong among the catalogue essays are those dealing with either technical innovation (Doris Carl, Michael Cole) or with competing cities (e.g. Florence and Siena), the rivalry of which prompted and influenced patronage as part of a lively dialogue that went in both directions (Scott Nethersole).

What is surprising though is the otherwise rather old-fashioned clinging to ideas Jacob Burkhardt would easily recognise and approve of. Today, the concept of an Italian and mostly Florentine renaissance is under debate and even the theory of a “renaissance” as an era of rebirth of classical antiquity has been challenged. It is a shame, therefore, that the geo-political, chronological and societal focus is drawn so tightly that it leaves out a great many aspects proposed by recent historiography and research, such as the influence of Burgundy, in particular during the fifteenth century, the networking between the courts of Europe and the fact that there was not just one important artistic centre in early modern Europe. Without wishing to take anything away from Florence’s role as a leading city in terms of art and patronage, it would have been good to hint more often at influences coming from outside Tuscany and to give greater space to the long “forgotten centuries” that would pick up and transform fifteenth-century art into mannerism. One could argue of course that some of these aspects are discussed in the catalogue and that such a fuller treatment would have made explode a highly ambitious exhibition. In my view though, the exhibition would have benefited from a slightly different approach and mindset that would have made it even more exciting and extraordinary than it is.

Fig. 5 Poster for Florence and Its Painters, Munich Alte Pinakothek (image in public domain)

So, yes, the above poster (Fig. 5) with Filippino Lippi’s Young Man in Sun Glasses promises a modern take on the arts of the Florentine quattrocento that is not quite kept in the galleries. It is still a very worthwhile exhibition to visit, beautifully arranged and displayed, but so much more profitable if the visitor reads the catalogue as well and, if possible, before entering the exhibition.

FLORENCE AND ITS PAINTERS: FROM GIOTTO TO LEONARDO DA VINCI, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, curator Andreas Schumacher, 18 October 2018–27 January 2019: https://www.pinakothek.de/en/florence