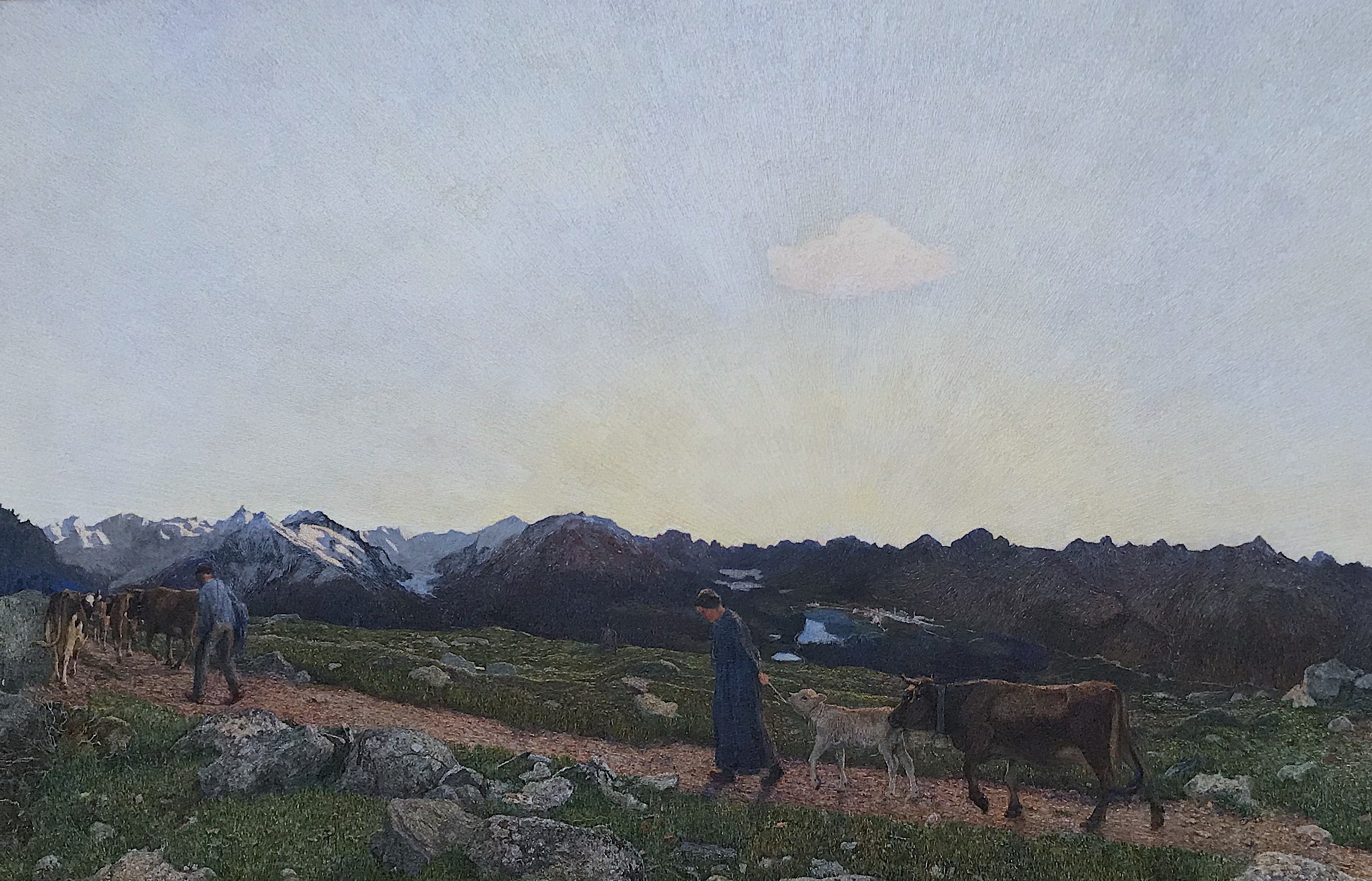

Giovanni Segantini, La Natura detail, 1897-8, Segantini Museum, St. Moritz (image public domain)

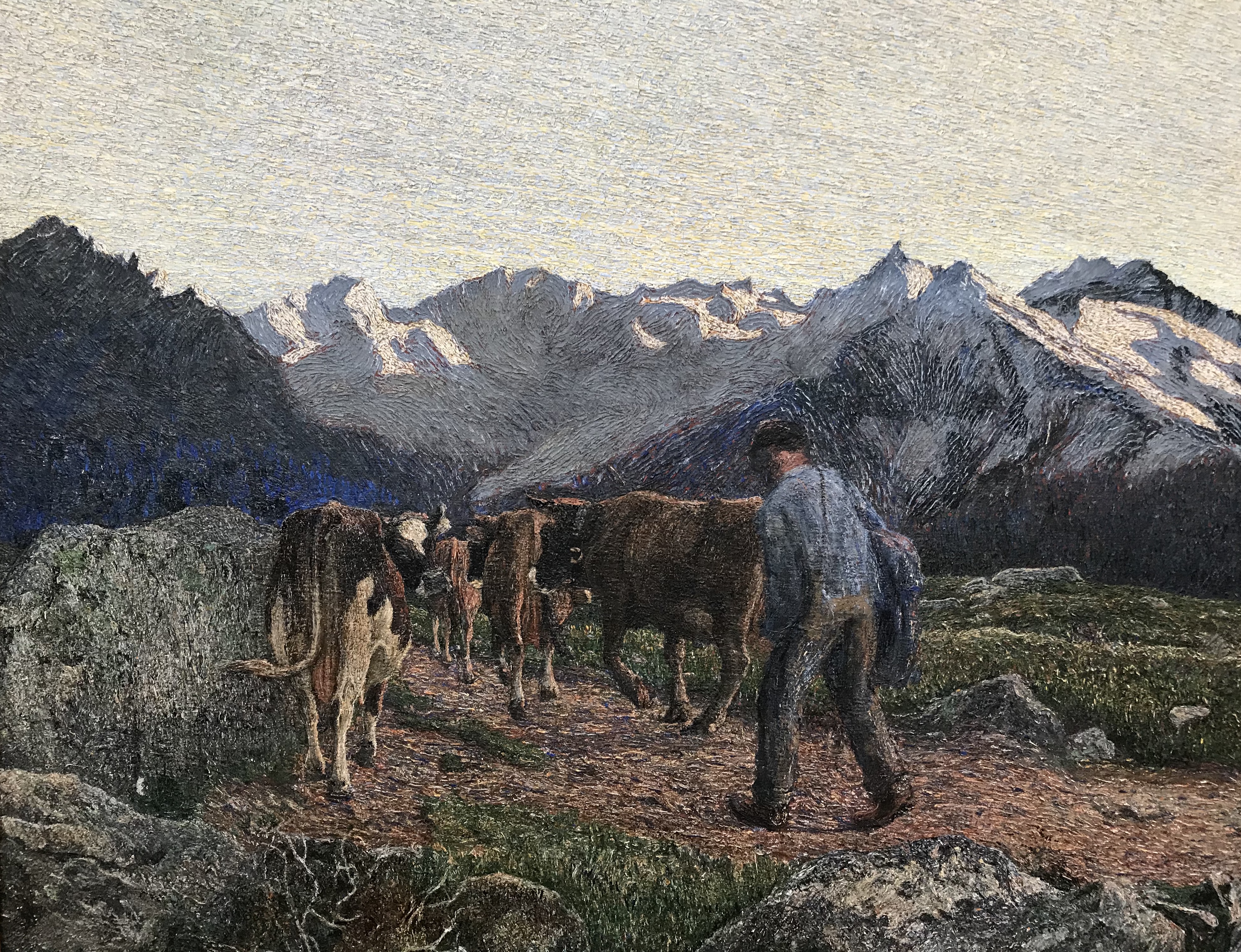

Giovanni Segantini, La Natura detail, 1897-8, Segantini Museum, St. Moritz (image public domain)

By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

Giovanni Segantini (1858-99) was not only a pastoral artist who loved mountains, especially the Alps around the Engadine above St. Moritz, but one who captured their majestic beauty in a landscape shared with people and animals in his Divisionist style of Symbolism. Even when dwarfed by nature, humans gain rather than lose value in Segantini’s art (see above image). His short life of 41 years – spectacular in its output – was often notable for his emphasis on a spiritual bond with nature rather than fondness for institutional religion combined with an unconventional social outlook. Although I’ve seen his work in Berlin, New York and in temporary exhibitions in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris, the best place to view his art corpus in the optimum context is in a specially museum in St. Moritz dedicated to his art.

Segantini, La Natura, (Triptych) ca. 1898, Segantini Museum, St. Moritz (image public domain)

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz, (image public domain)

The Segantini Museum above St. Moritz and the lake houses at least fifteen of his best canvases, including some of his most famous works, some of them gigantic proportions that he painted on a huge easel high in the mountains. Sadly, in 1899 Segantini died from complications of a burst appendix high on the Schafberg mountain above Pontresina where he preferred to paint outdoors; his son was sent down to fetch a doctor but it was too late.

Segantini, Early Mass, ca. 1885, Segantini Museum (image courtesy of Segantini Museum)

One of his first works to garner attention – particularly from Milanese dealer Vittore Grubici who helped sponsor the young artist who was only functionally literate but who had profited from an artistic education at Milan’s Accademia di Brera – was his above 1885 painting of a priest Early Mass (overpainted from a young “Sinner” girl the Church judged harshly). The church can be seen on the left behind the stairs where a shriveled priest climbs to perform his duties but Segantini seems to have more natural awe for the morning sky with a dim full moon. It seems to be one of the few paintings Segantini’s full signature in which is so prominent, possibly because he was not happy with the Church to force him to repaint it.`

Segantini, Ave Maria Crossing the Lake, 1886 Segantini Museum, St. Moritz (image P. Hunt, 2018)

His Ave Maria Crossing the Lake (1886) above, despite the name is more about Nature than any institutional religious context. This painting is remarkable for its reflected light and nearly silhouetted subject. In it the young affectionate mother with head bent to her clinging child (Mary and Jesus?) are in the front of a boat with a rowing shepherd (Joseph?) at the boat rear. The rower is almost asleep at the oars while ferrying sheep across a lake at dawn or sunset. The lake ripples brilliantly break up the reflected boat image below.

Segantini, Mother and Child detail of Ave Maria (image P. Hunt, 2018)

If this is the Holy Family (and a subtle evocation of the Lamb of God), it may remind of Caravaggio for its elevation of simple peasants into a sublime story where a simple wood frame over the boat creates a double arcade like a dual halo; the church on the horizon is so small it must be a deliberate philosophical statement about true piety likely transcending any ritual.

Segantini, sheep detail of Ave Maria (image P. Hunt, 2018)

Reflected light rippling on the lake water and the light also reflected off the sheep backs is likewise profound: Nature offers its own worship in a vast outdoors rather than in a church building. Perhaps what is sacred doesn’t seem to need affirmation from clergy in Segantini’s view. Two sheep in the foreground appear to almost dip their heads into the lake water to drink, their own proximity echoing the endearing bond of the mother and child.

Another alpine picture among Segantini’s most famous is his Primavera sulle alpini of 1897, or Spring under the Alps. His en plein air technique of preferring painting outside to studio painting is shown here in what he termed his style of natural symbolism where this outdoor light is clear; no single light source other than what pours from the sky. Segantini’s philosophy is easily summarized in his statement, “I’ve got God inside me, I don’t need to go to church.” His unfinished triple masterpiece series is his triptych (Life, Nature, Death) was commissioned for the Paris 1900 Exposition Universelle and remains his most famous set of paintings, now housed upstairs in the rotunda of the Segantini Museum of St. Moritz, definitely much more worth a visit than the glitzy casino nightlife of this famous Engadine town.

Segantini, Primavera sulle alpini, 1897, private collection (image public domain)

Segantini, Primavera sulle alpini, 1897, private collection (image public domain)