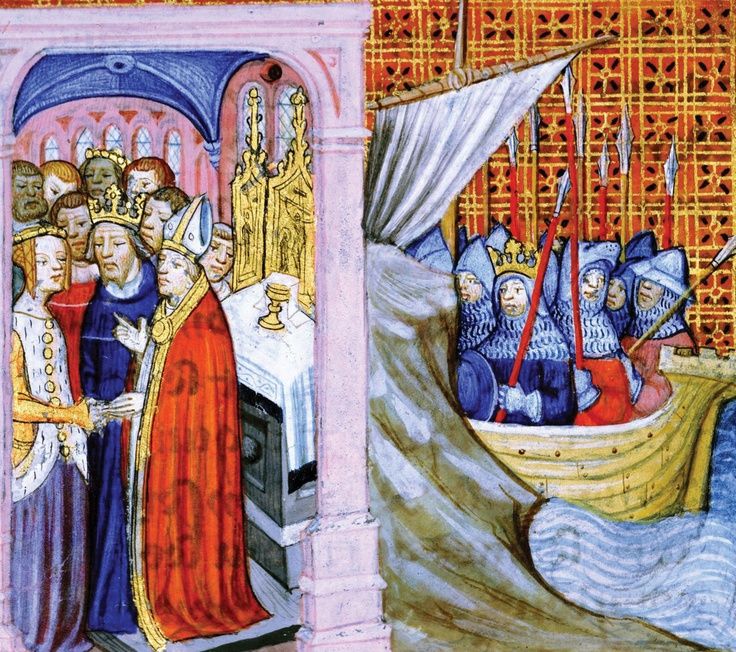

Marriage of Eleanor and Louis VII and Louis Leaving for Crusade, 15th c., Chroniques de St. Denis (image public domain)

Marriage of Eleanor and Louis VII and Louis Leaving for Crusade, 15th c., Chroniques de St. Denis (image public domain)

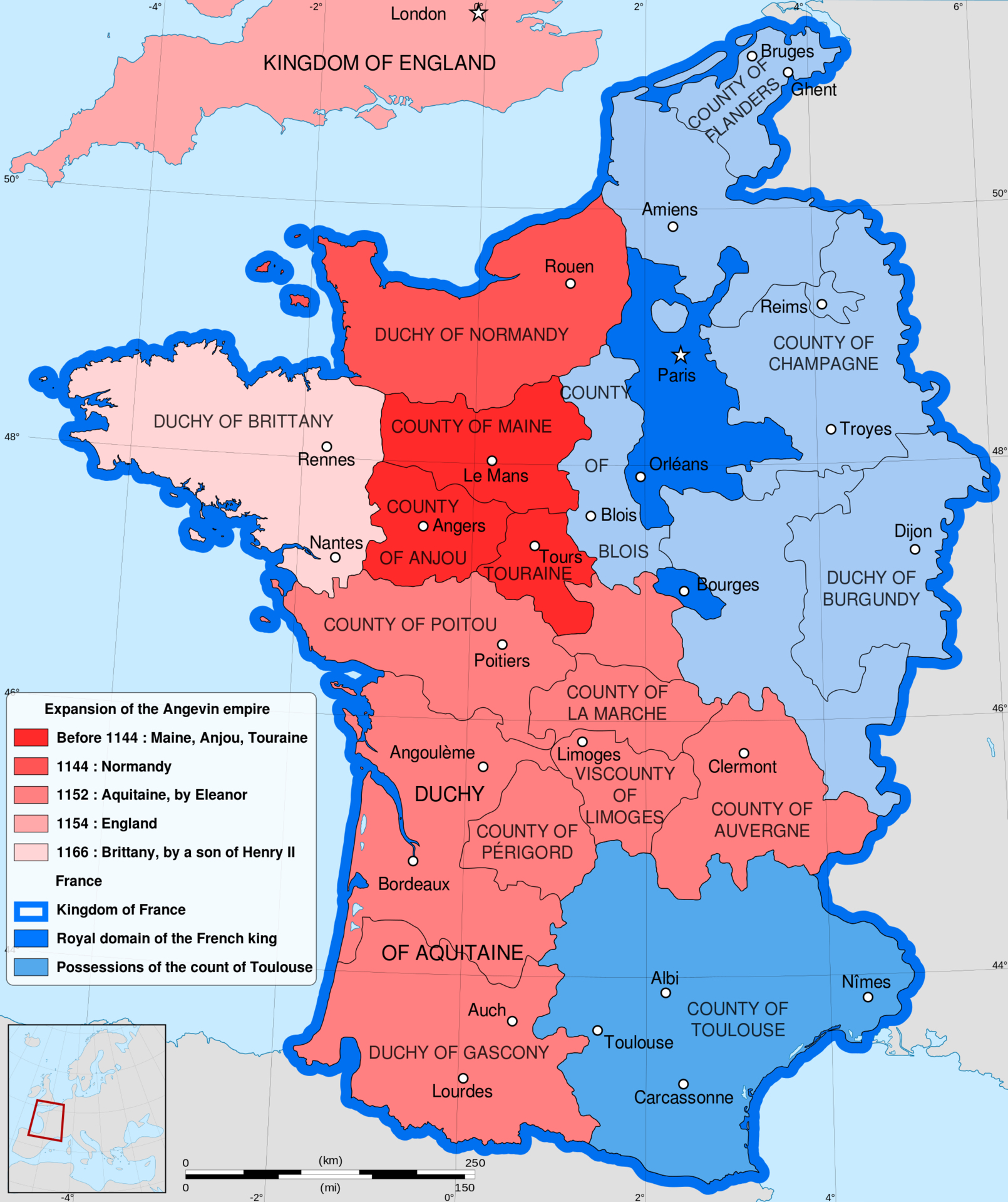

By Emmanuel Zilber –

Defying so many male imposed status quo “rules”, Eleanor of Aquitaine (ca. 1124-1204) was remarkable, but not only for being the wife of two kings and mother of three kings. How many famous men owe so much to their wives or mothers? We remember King Richard I the Lionheart, but rarely acknowledge his mother Eleanor, who would have called herself Aliénor although in English we mostly use her Anglicized name.[1]

During the 12th and 13th centuries, women were mostly perceived as inferior to men in the eyes of men. Women were considered undesirable for holding land, as the family dynasty would lose its territory once the women married, and they were seen only as tools for politics: individuals who could be married off and secure alliances with the patriarch of another family. Eleanor, however, is remembered in history as one of the greatest leaders, patron of the arts, and matriarchs of the middle early ages, as well as a hugely significant historical figure on history’s timeline.

Map of France (including Duchies and Counties) in 12th c. (image public domain)

Eleanor of Aquitaine was born to William X, Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers. Aquitaine was a sought after region: a vast piece of real estate that France had been trying to keep within its hegemony although “France” at the time was mostly a loose aggregate of duchies (like Aquitaine) or counties under nominal Capetian kingship. In 1137, Aquitaine’s William X died, and all his possessions went to his only child, Eleanor, a young woman only fifteen years old. Upon her father’s death, she was married off to the king of France, Louis VII that year (1137). At such a young age, Eleanor was thrown into the high stakes game of royal politics and courtly maneuvering. Her 15 year marriage to Louis VII was not a happy one, however, and they agreed to an annulment in 1152. Six months after the annulment, Eleanor married Henry II, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, where she would rise with him to power as future King and Queen of England. Aquitaine also grew and developed over this time, becoming a legendary center of poetry, romance and courtly love, where Eleanor could become a patron of troubadours. During her time as Queen, she manipulated many different events as well, even going so far as to stage a rebellion with her sons against Henry II. Therefore, Eleanor of Aquitaine not only left a tremendous cultural legacy, but also wielded and maneuvered significant political power in France and England to such an extent that she defined herself as no ordinary Queen, but instead one of the strongest and wisest leaders of her time.

Effigy of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Fontrevaud Abbey Church, Anjou (image public domain)

While Eleanor of Aquitaine never officially ruled a kingdom, she wielded as much power and influence as a King especially in his absence. By first marrying the King of France, Eleanor could learn the ways of politics and navigate herself through a royal court. Though she was still young and barred from publicly advising her first husband, Louis VII, she served as a private counsel. If the marriage did not last long, was it most likely because she didn’t produce a son? Nevertheless, the royal partnership brought her influence, power, and recognition in the world. Through marrying Henry, she was able to own lands spanning from Spain all the way to Scotland. No queen ordinarily presided over such a vast land, but Eleanor of Aquitaine’s duties became more than simply public appearance. She dignified herself as a wise leader, managing to assist in the administration and strategy of ruling the Angevin Empire for herself and for her sons. Jean Markale notes “Eleanor […] possessed a keen intelligence that she exhibited every moment of her life […] she was a powerful woman, the holder of sovereignty over a large domain and perfectly aware of the political role she could play.” [2]

Eleanor, from a young age, was placed in a position of power, and with her beauty and intelligence, Eleanor was able to use that power to its fullest potential. Marion Meade also explains, “Although she never ruled a kingdom in her own right, she wielded more influence than many monarchs, demonstrating what a courageous and determined woman could achieve despite the misogynistic forces within the church and society…Her influence on twelfth century history and culture exceeded that of any other woman of her time.” [3]

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Donor Portrait in Psalter of Eleanor of Aquitaine, ca. 1185, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague, Netherlands (Courtesy of Koninlijke Bibliotheek)

During Henry’s absences, she would preside over courts at Westminster and Normandy, as well as issue writs and documents for the Kingdom’s management. She granted her favorite son, Richard, the Duchy of Aquitaine, but was often the person he sought after for guidance and aid. According to Alison Weir, upon his coronation as Duke, she strategically crowned Richard with a coronet, used when she herself was crowned Queen of England, subtly making it clear Eleanor was still very much in control of Aquitaine and her son as regent . She demonstrated her acute political savvy no more so than in the attempted revolt of her sons. Henry the Younger, the eldest of her sons, had grown tired of his lack of power and sovereignty, and prepared to fight his father, Henry II, for control of the Angevin Empire. Henry the Younger, though, needed allies on his side to fight his powerful father. Eleanor, hosting Richard and her younger son, Geoffrey, urged her sons to join their brother in his cause. Theories on why she convinced her sons to join the war against Henry abound, though most concur the decision was based on power she could yield. According to Weir, Eleanor employed a strategy or garnering a coalition in order to aid Henry the Younger. She adeptly persuaded her sons to join the cause, utilized the grievances or regional lords to join against Henry II, and played on the ambitions of her ex-husband King Louis VII of France to increase the force of her sons’ armies. Henry II quickly learned of Eleanor’s conspiracies, and imprisoned her. Without her, the war effort fell apart, and though the sons were forgiven for their treason, Eleanor was made a prisoner for the remainder of Henry II’s life. Once Henry died, she was released from her confinement, and served as an integral counsel for the now King Richard I the Lionheart.

Effigy of Richard I Lionheart, Fontrevaud Abbey, Anjou (image public domain)

While Richard was away on the Third Crusade (1189-92), Eleanor tended to the affairs of England: she rode from region to region requiring that all lords must swear fealty to Richard. Roger of Wendover (recorded in Alison Weir) wrote, “She arranged matters in the kingdom according to her own pleasure, and the nobles were instructed to obey her in every respect.” She issued acts ranging from measures on corn and liquids to new standards of coinage, and the Southern Queen transformed into a popular figure in England. Though Richard, on one of his attempts to take the Holy Land, appointed Hugh de Puiset and William Longchamp to serve as official chancellors, as Weir writes, Puiset and Longchamp both looked up to Eleanor for advice, and obeyed her as though she was the leader of the Kingdom. Richard’s time in England was sparse, only serving three out of ten of his years in his domains, and as such Eleanor was left to defend against encroaching hostilities from Philip II of France. In one instance, the King of France deceived Eleanor’s son, John, offering him land and power if he plotted against King Richard. Eleanor immediately learned of such intrigue, and swiftly put down the attempted treason, once more travelling around Richard’s realm and ordering the fealty of his lords. Much of Eleanor’s later years in life were dedicated to ruling the Angevin Empire; her proficiency and wisdom gives credence to her exemplary political acumen and power no Queen during her time held. A true “working woman” of the medieval world, some early modern “psychologizing castigated queens such as Eleanor of Aquitaine for their lack of involvement with their offspring”, but this early theorizing of medieval childhood contradicts the prevailing consensus and clearly doesn’t hold water given her advocacy for them. [4]

Sigilium of Aliénor, Duchess d’Aquitaine and Comtesse of Anjou (image public domain)

During Eleanor’s reign in Aquitaine, she allegedly triumphed over many artistic and literary achievements. Although the “Court of Love” did exist, the historical consensus agrees the literary and artistic achievements at Poitiers are most likely exaggerated, and ought to be more closely described as “legend” rather than fact. While the largest achievements may have been fiction, there is indeed some truth to Eleanor’s patronage and “judgments” of Troubadours. Jean Markale writes, “During her life and after, she was quickly made into a heroine of courtly romance, a particularly colorful symbol of the ideal women of the twelfth century.” While some accounts of literary and artistic achievement existing in Aquitaine date back to William IX, Eleanor was able to return her court and serve as the most visible patroness for romance, poetry, and art. As Meade concurs, “If it was not the government Henry had hoped to install [in Aquitaine], it was one that reflected Eleanor and her conceptions of the ideal state: music and poetry, love and laughter, freedom, justice, and a modicum of order. In the [eleven] sixties and seventies, all roads in Aquitaine lead to Poitiers and to the ducal palace, where events were taking place that intrigued the Aquitanians and amazed the rest of Europe.” Eleanor would often sit and listen to quarrels of lovers, acting as a jury with several other members of her court. The court would listen to their questions on love, and rule on matters of romance. It is said around twenty-one cases were heard, the most famous one revolving around whether true love could exist for marriage. Eleanor’s court of love had important cultural implications in the nature and concept of love and romance during the Middle Ages, shaping contemporary thought on the matter. Eleanor’s patronage did indeed turn Poitiers into a center of poetry music, art, and literature, although to the degree of how much is still contested. Regardless, Eleanor’s reputation for her courtly influence is mostly intact and this looming influence has transformed her into a cultural legacy worth examining. Her shaping of the rules of chivalry are probably worthy of acknowledgement.

By the time of her death in 1204 at 80 years old, Eleanor of Aquitaine was acknowledged as one of the most impressive women of medieval history; she defied the traditional role of queens, and distinguished herself as a figure worth admiring. She aided her city in the transformation of a center of culture and art, obtaining literary and poetic achievements, and controlled a very strong territorial empire. Eleanor achieved far more than many queens of her time: she was tough, smart, beautiful, and powerful. Her skills and wisdom made her one of the most revered figures of her time. Powerful men often came to her and sought her help when her sons were absent or too stubborn to listen to advisors. Eleanor of Aquitaine held tremendous political power in two medieval countries, as well as leaving a significant cultural legacy.

Notes:

[1] Alison Weir. Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Life. New York: Ballantine Books (Jonathan Cape, 1999), Preface, iv, and elsewhere.

[2] Jean Markale. Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of there Troubadours. Inner Traditions, 2007.

[3] Marion Meade. Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Biography. Penguin Books, 1991.

[4] Lisa Hilton. Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2008, 6.