Eagle and Snake, Imperial Palace Mosaic Museum, Istanbul, circa 6th c. (image in common domain)

By Patrick Hunt –

Courtesy of the Nikia and Hippodrome revolts of 532 that destroyed part of the Imperial Palace of Constantine in Constantinople, subsequent rebuilding by Justinian (reigning 527-65) and possibly added to by Heraclius (reigning 610-41) created a mosaic peristyle colonnaded court with imperial mosaics that made up part of the new palace adjacent to the Hippodrome. These mosaics in Late Roman style are among the highest quality stylistically and thematically from Late Antiquity. What has survived and on view in the Great Palace Museum at Arasta Square near the Sultan Ahmet (“Blue Mosque”) complex constitutes roughly a seventh of the original plan.

Imperial Palace Mosaic Museum Floor section (photo Patrick Hunt, 2014)

Turkish authorities in Istanbul and academic institutions such as Ankara University in collaboration with the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and the Austrian Academy of Science, among others, jointly conducted excavations from 1935-38 and 1952-54 and finalized in 1983-87. The Great Palace Mosaic Museum opened in 1987 to highlight these singular mosaics, claimed to be the “most magnificent landscape examples to have survived from ancient times” and best in “size and quality”. [1]

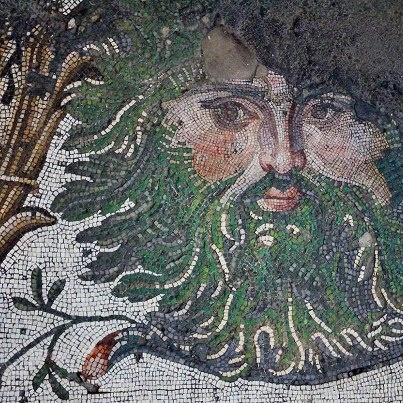

Great “Human” Head in Acanthus Border Surround, Imperial Palace Mosaic Museum (image common domain)

The mosaic background is mainly white tessera in circling scallop patterns with highly-colored images and the mainly rural subjects range from subtle imperial tropes like the great eagle to bucolic nature and animal domestication, shepherds and gooseherds, hunting scenes, elephants, tigers, stags, bears, donkeys and fishermen, children at play, a bearded but balding old “philosopher” seated on a rock, possibly mythic or hybrid creatures like a possible griffin or “lion-goat”, and even myth scenes like Bellerophon and the Chimaera, the Infant Dionysus on Pan, as well as the four seasons symbolism in the guise of humans heads, especially embedded in acanthus leaves in the 50 meter wide frame that surrounds the interior scenes. There may have been other myth scenes that are now missing from the surviving remains.

“Lion-Goat” Eating Lizard, Imperial Palace Mosaic Museum (image public domain)

The human faces of hunters and children often show emotive expressions of intense but simple force (e.g. the children with animals, some of the hunting scenes with dangerous animals charging). The dynamism of these mosaics suggests that while undepicted urban life in the imperial city might show a wide spectrum of normal human hierarchical relations, on the other hand, outside the city but inside the palace, contrasting nature is filled with another ebb and flow of life and death and violent predation supposedly unlike calmer human interactions. As an aesthetic meditation on nature, the palace mosaic is no Arcadian idyll but rather a dynamic display of what might be encountered outside the imperial domain in much more rural contexts where animal power might be brokered on its own, amoral terms.

Donkey Fed by a Youth, Imperial Palace Mosaic Museum (image public domain)

The most famous individual mosaic motif in the Imperial Palace Museum may be the battling eagle and snake seen in the above lead image. Often interpreted as the power of the Empire or Emperor and the capital city Constantinople wrestling with besieging enemy forces, the eagle fights a snake coiled around it but the outcome often is suggested that the eagle will be victorious. The museum’s published text suggests the eagle is the Eastern Empire administered from Constantinople in its triumph over enemies and that a similar arrangement of images may have been employed by Alexander the Great at Babylon in 324 BCE as Plutarch relates in the huge funeral pyre of Hephaistion designed by Stasicrates that may have reached 60 meters high, often called the most expensive funeral in history, costing 10,000 talents. [2]

The Imperial Palace Mosaic Museum is not usually on the main tourist itinerary in Istanbul and the times I have visited were fairly low visitor density. Sometimes in intense light, the attendant shadows make it difficult to take good photos but the museum encourages visitors to visit – with an inexpensive entrance ticket fee – and to photograph these best examples of surviving Early Byzantine mosaic scenes. If not much remains, what does is an exquisite reminder of the aesthetics of the 6th century and the likely staggering amount of imperial revenue supporting art. As Cormack reminds, the light in antiquity – either direct sunlight from above or by candelabra [3] – was likely not much better, but these imperial mosaics are worth the effort to view and remember.

Notes:

[1] Erdem Yusel, ed. Great Palace Mosaic Museum. Istanbul: Bilkent Kultur Girismi Publications, 2010, 6, 11.

[2] Plutarch, Life of Alexander 72.4

[3] Robin Cormack. Byzantine Art. Oxford History of Art Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd ed. 2018, 1.