A. Van Dyck, Charles I (triple portrait) Royal Collection ca. 1635

By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Charles I, the second Stuart king of England, is for most of us the unlucky monarch who lost his head and his throne on scaffolding in front of The Banqueting House in Whitehall, London. While we may be aware in general that King Charles was also a great connoisseur and patron of the arts, it is always useful to be reminded of his activities as collector – not least since the works of art he amassed were sold after his death in the great Commonwealth Sale and then re-bought, as far as possible, by his son and successor Charles II during the Restoration. His collection thus plays a major part in at least two distinctive episodes in the history of dynastic collecting as well as being closely connected to collections and collectors throughout Europe. At the moment, two exhibitions in London tell the tale of the creation, expansion, loss and reconstruction of one of the most important royal collections on the British Isles. By doing so, they also take the spectator on a journey through the political and cultural history of a northern realm too often considered to be situated far from the artistic centres of early-modern Europe. The exhibitions shown at the Royal Academy and at the Queen’s Gallery impressively prove that England and her monarchs were not held back by little things such as location but rather engaged in a lively cultural exchange with their peers and with artists and agents on the Continent.

In England – as in parts of Europe – collecting had long been tied to dynastic claims and ambitions. A new dynasty would commission and/or collect similar works of art as had their predecessors, for example to legitimise their own rule. In other cases, certain imagery or modes of display had made such an impact that the new royal house wished to refer to the former monarchs with all the connotations it entailed. The Tudors thus reclaimed Plantagenet and Yorkist (by marriage) court culture, while the Stuart kings of England strongly identified with their Tudor relatives after succeeding to their throne on the death of Elizabeth I in 1603. While James I’s main cultural interests had mainly focused on antiquarian studies, his son Charles soon acquired fame as an art enthusiast on a much wider scale who combined a whole range of artistic influences, historical and contemporaneous, as the foundation of his patronage. After all, Charles had been the “spare” heir to the throne until the premature death of his brother Henry in 1612 but this pivotal calamity not only propelled him forward onto the political stage, it also meant that he was from now on exposed to important cultural leverage from the in- and outside of his future kingdom.

Roman, Aphrodite (‘The Crouching Venus’), second century CE

Roman, Aphrodite (‘The Crouching Venus’), second century CE

Marble, height 119 cm

RCIN 69746

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Exhibition organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust

An important dynastic step for such a young man would have been the search for an appropriate bride and it looks as if Charles made the most of the negotiations starting with the Spanish Habsburgs by visiting the Peninsula in person in the company of his favourite George Villiers in 1623. Even though this lengthy stay did not bring about the wished for result, it made an enormous impression on the young prince who may well have decided there and then that he would try to build a collection of similar rank in due course, fuelled not least by gifts and purchases made at the time (cat. 16). The fact that he eventually married a French princess (with Italian roots) reinforced and modified this decision. Henrietta Maria’s cultural heritage would remain of great importance throughout Charles’s reign and, eventually, during that of their son and heir Charles II. What must also be remembered is the cosmopolitan aspect of a royal court that combined Scottish, English, Danish, Spanish, French and Italian traditions in an attempt to underpin the validity of Stuart rule.

Andrea Mantegna (1430–1506), The Triumph of Caesar: The Vase Bearers, c. 1485–1506

Tempera on canvas, 269.5 x 280 cm

RCIN 403961

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Exhibition organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust

Indeed, when the Gonzaga collection, comprising antiquities (cats. 19-24), paintings and – in particular – Mantegna’s famous Trionfi (cats. 25-33) came on the market, Charles I did not hesitate to make a successful bid in 1627. As the new owner he was able to present himself as a putative descendent of the ancient Caesars who had ruled over a large and international empire.

Charles I: King and Collector

27 January 2018 to 15 April 2018

Key. 1 / Cat. 76

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Charles I in the Hunting Field, c. 1636

Oil on canvas, 266 x 207 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris, Department of Paintings, inv. 1236

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Christian Jean

Exhibition organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust

Charles I understood the importance and impact of royal portraiture and of such state portraits to be displayed in state rooms. In one case we know that he had a highly finished triple portrait executed by Anthony van Dyck in 1636 (cat. 3) and sent to the famous Italian sculptor Bernini who created the ordered bust of the king but kept the painting in Rome. The bust was lost in the fire of Whitehall Palace in 1698 but the Flemish sculptor François Dieussart had probably executed a portrait after Van Dyck’s painting for the Earl of Arundel (cat. 2). When a portrait of the queen was executed for the same reason later on, Bernini seems to have refused the commission, however, although we cannot tell exactly what happened at the time – the painting may not have been sent to the artist (cat. 9). Generally though, Bernini preferred to work on his sketches and designs with the living sitter in front of him and was less willing to make an exception for Henrietta Maria than for the king.

Charles I: King and Collector

27 January 2018 to 15 April 2018

Key. 64 / Cat. 3

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Charles I in Three Positions, 1635–36

Oil on canvas, 84.4 x 99.4 cm

RCIN 404420

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Exhibition organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust

Apart from his early marble bust, there are several other state portraits displayed in the Royal Academy exhibition, on horseback (cats. 72-74) and in the hunting field (cat. 76). Perhaps the most impressive is the so-called “Greate Peece” (cat. 66, preparatory oil sketch cat. 65) of 1632, showing the royal couple with two of their children in a state portrayal that harked back in spirit to the Whitehall Mural commissioned by Henry VIII from Hans Holbein in 1537. Obviously meant as a declaration of dynasty and of a divine right to rule, the great state portrait introduced the next generation of Stuarts in a setting that seemed to announce the longevity and inevitability of their kingship. Another, presumably less formal group portrait of the five eldest royal children – painted by Van Dyck – together with a rather lovely large dog of a now extinct breed was once displayed in the King’s Breakfast Chamber at Whitehall Palace (cat. 70).

Van Dyck’s paintings clearly dominate the exhibition and may once have been in the majority among the works of art commissioned by King Charles. Nonetheless, a great many works of other masters were commissioned and collected from abroad. The Trionfi were by no means the only example of Italian art being brought to Britain, for Charles I also employed Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi (cats. 84-88) as well as importing works by Cristofano Allori (cat. 89) and in particular by Guido Reni for his collection (cat. 90). The exhibition at the Royal Academy thus assembles the international (Northern and Italian) artistic influences on the Caroline court and, even better, discusses the diverse patronage of king and queen within the context of European court culture and on the basis of a changeable art market populated by artists, agents and merchants such as Daniel Nijs.

While antiquities and early-modern state portraits played an important part in Charles I’s collections, they were complemented by other collectibles such as small-scale valuables in the tradition of other collections and forms of display both in England and on the Continent, where they had frequently been used to underpin dynastic claims and princely ambitions, for example in the scrittoi of Medici Florence (cats. 115-138: small bronzes, miniature portraits, ancient cameos, coins and medals). Long overlooked by scholarship, such collections also existed on the British Isles from the fifteenth century onwards, when they had been massively influenced by Burgundian court culture. During the rule of King Edward IV, whose sister Margaret of York had married Charles the Rash, Duke of Burgundy, in 1468, this type of cultural impact was so strong that the king had introduced the Black Book of Burgundian court ceremonial in England. Even though the House of York was eventually superseded by the House of Tudor after the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, many such elements were adopted by the new dynasty and by their courtiers. A similar development can again be observed in the early years of the seventeenth century.

One particular feature of this process of cultural adoption by collecting, was the import of Flemish tapestries which were able to fulfil a range of tasks, decorative and practical, and had long played an important role in royal and princely households and economies. Emperor Charles V as descendant of Charles the Rash had founded a tapestry workshop in Brussels in the 1540s, a move that was going to be imitated in Ferrara and Mantua and by Duke Cosimo I in Florence from 1545. In England a royal tapestry workshop had been founded (among several others, including one for armour) by King James I at Mortlake in 1619. Charles I continued to commission such works with (mostly) religious scenes created after cartoons by Raphael and with borders designed by Francis Cleyn.

The full tragedy of the fates of king and collection become apparent from Abraham van der Doort’s Catalogue of the Collections of Charles I compiled in 1639 (cat. 140). The list was drawn up by the Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and kept by him up to his death in 1640. There are three further fair copies for which the one in the RA exhibition served as the basis. Dispersed during the Commonwealth Sale of 1649, the king’s treasures went to collectors in England and on the Continent, where many pieces are preserved in former Royal Collections, e.g. at the Louvre, to this day. Henrietta Maria had been able to flee in 1644 and spent the following years with their children in her native France. The British republic only lasted for about a decade and in 1660 Charles II returned from exile to start a period of Restoration. He also tried to regain as much of his father’s collection as possible and bought and commissioned works of art to replace what had been lost, e.g. to be used at his coronation in 1661 (cats. 23-27).

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-77)

The Coronation of Charles the II in Westminster Abbey the 23 of April 1661, 1662

Etching | 36.0 x 48.0 cm | RCIN 805164

The exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery, therefore, attempts to recreate the lively and glamorous court culture of Charles II with its society made up of diplomats, artists, actors and scientists (pp. 383-405). Since Charles II understood very well the connections between art and power, it became one of his foremost preoccupations to restore his father’s collection in order to underpin his own dynastic claims. An order, soon to become a law, was passed which declared that everyone holding works of art acquired at the Commonwealth Sale should return them to the royal palaces (cat. 124). Through the efforts of a special committee Charles II managed eventually to reassemble over 1,000 paintings as well as other works of art, many of which had once been the property of his father. Other collectibles arrived as diplomatic gifts, for example the splendid Exeter Salt, created in c.1630 in Hamburg (cat. 31). He also seems to have been unusually conscious of the importance of his own portrait in painting, drawing and (mezzotint) print and commissioned a high number of such likenesses from his early years in exile onwards (cat. 162).

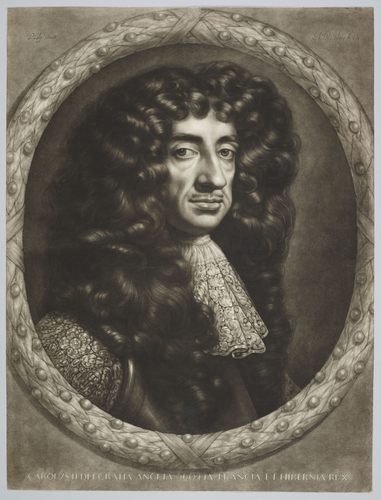

Abraham Blooteling (1640-90) after Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680)

Charles II c.1680-90

Mezzotint | 68.3 x 51.5 cm | RCIN 602538

One of the most impressive state portraits, executed most likely during the 1670s, is the one showing him in his coronation robes and holding the recreated regalia in a very formal pose that seems to recall Van Dyck’s Greate Peece as well as Tudor state portraiture (cats. 49 & 65). It is used to legitimise Stuart reign as part of a natural order of kingship.

In the case of Charles II, the French court was going to play a major influence, in particular as far as fashion and material culture was concerned. But his Portuguese wife, Catherine of Braganza (cat. 53), not only brought a large dowry; as a result of their marriage, Portuguese colonies e.g. on the Indian Subcontinent and in Morocco including Bombay and Tangier (cat. 172) became part of the realm and somewhat balanced Catherine’s failure to produce the desired heir. While her cultural impact on court life has not received enough scholarly attention until recently (see for example www.marryingcultures.eu/research/catherine-braganza), it most likely was comparable to that of Henrietta Maria. Catherine stayed in England after the death of her husband in 1685, but later returned to Portugal where she looked after the governing of her brother’s kingdom, while he was incapacitated by illness.

Jacob Huysmans (c. 1633-96)

Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705) c. 1662-64

Oil on canvas | 216.5 x 148.7 cm | RCIN 405665

The rising artistic star during the final years of Charles I had been a Dutch portraitist who arrived in England in the early 1640s, (Sir) Peter Lely. He was a collector and connoisseur, would acquire many works of art during the Commonwealth Sale of 1649-51. Lely made a notable career for himself both during the Commonwealth as during the Restoration under Charles II (see: Painted Ladies: Women at the Court of Charles II, 2001/2002 at the National Gallery, London and at the Yale Center for British Art). Today he is still famous for his portraits of Windsor Beauties (pp. 132-39) who included many a sleepy-eyed depiction of the king’s mistresses, among them Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, in the guise of Athena (cat. 57). Even though these portraits were not exact likenesses, since the artist preferred (or was ordered) to flatter his sitters. Barbara Villiers became the mother of five royal children and was painted by Lely several times in allegorical styles.

Both exhibitions are to be recommended on their own, since they give such an impressive picture of the respective court culture, artistic development and scientific progress during the rule of Charles I and Charles II. At present, however, there exists the chance to view them together in one day and thus to appreciate the similarity and contrast between the two courts as well as the impact of the Commonwealth in between. The show at the Queen’s Gallery takes the narrative even further throughout the long seventeenth century and includes the rule of Charles II’s brother and beyond to the end of the Stuart dynasty in Britain with the rule of Queen Anne.

While the exhibition Charles I: King and Collector focuses on the building of a major collection and its use as part of Stuart politics, its great merit lies in the reassembling of a great number of Italian, Northern and English masterworks that were once part of the collection and thus by providing the material context that once served as the background for the collectibles. Its counterpart Charles II: Art & Power instead emphasises the glamorous court culture reinstated after the end of the Commonwealth and in pace with the reacquisition of as many works of art as possible. It also attests to the prominent role images in diverse media were going to play for court culture and politics right through the second half of the seventeenth century.

Charles I: King and Collector, organised by the Royal Academy in partnership with the Royal Collection Trust, Royal Academy of the Arts, 27 January – 15 April 2018, curators and editors Per Rumberg and Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Royal Academy of the Arts, London 2018.

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/charles-i-king-and-collector

and

Charles II: Art and Power, organised by the Royal Collection Trust, The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 8 December 2017 – 13 May 2018, curators and editors Rufus Bird, Olivia Fryman and Martin Clayton, Royal Collection Trust, London 2017.

https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/charles-ii-art-power/the-queens-gallery-buckingham-palace