By Catherine Clover –

By its definition, the Beaux Arts movement in architecture combined the classical proportions of the Greco–Roman period with the Neo-Classical decorative elements popularized in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Of the many buildings that fall into this category of architecture, two prominent international opera houses come to mind – the Palais Garnier (1861-75) in Paris and the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco (1932). The revivalist style was widely popular with those wishing to commission large-scale public and private works in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today it is represented in places where students of the famed Ecole de Beaux-Arts in Paris or students of similar schools of architecture and fine arts received commissions to work.

One such student was Mario Tamagno (1877-1941), an Italian architect from the Piemonte region. After graduating from the esteemed Royal Albertina Academy of Fine Arts in Turin, Italy in 1895, he first gained employment teaching architecture at his alma mater in Turin. Tamagno’s sensitivity to design forms outside of the European lexicon caught the attention of fellow Italians working for the Siamese government seeking to fill positions in the newly formed Office of Public Works in Bangkok [1]. The Siamese government invited Tamagno to come to Bangkok and join the team of fellow Italians, including Annibale Rigotti, working on several large-scale royal projects. The lucrative contract spanned a twenty-five year period, [2] from 1900-1925, and it provided Tamagno the opportunity to travel to a foreign land full of new and inspiring architectural styles. In the years following his arrival in Bangkok, his repertoire of works included buildings, bridges and monuments combining classic Italian design elements with a Siamese twist. In his designs one finds a symbiotic use of local building materials, such as carved teak and wrought iron alongside imported Italian materials including marble, granite and carved stone.

One of his early collaborations with fellow Italian architects after arriving in Siam was a Buddhist Temple called Wat Benchamabopit, also known as the marble temple because of the large amount of Italian marble featured in its design. After the return of King Chulalongkorn from Europe in 1907 and following the success of Tamagno’s Siamese Pavilion erected at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, the Siamese government named Tamagno as Siam’s Chief Architect. [3] During his twenty five years in Bangkok he was part of the Italian team responsible for such royal works as Abhisek Dusit Throne Hall and Suan Kularb Residential Hall in the grounds of the Dusit Palace, Bang Khun Prom Palace, the former residence of Prince Paribatra Sukhumbhand and Phitsanulok Mansion, now serving as the official residence of the Prime Minister of Thailand.

Hua Lamphong, or Krungthep, train station (c. 1916) in central Bangkok is another prominent example of his collaborative work in Bangkok that is still in use and easily accessible to visitors today. With two flanking towers on either end of a rounded train shed, the design of Hua Lamphong is distinctly Beaux Arts in style. Its structure and form recall the grandeur of world’s fair pavilions seen in Chicago, St. Louis and San Francisco at the turn of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. [4] Fittingly, the grand station today still serves the famed historic rail service of the Eastern and Oriental Express running from Singapore to Bangkok and beyond.

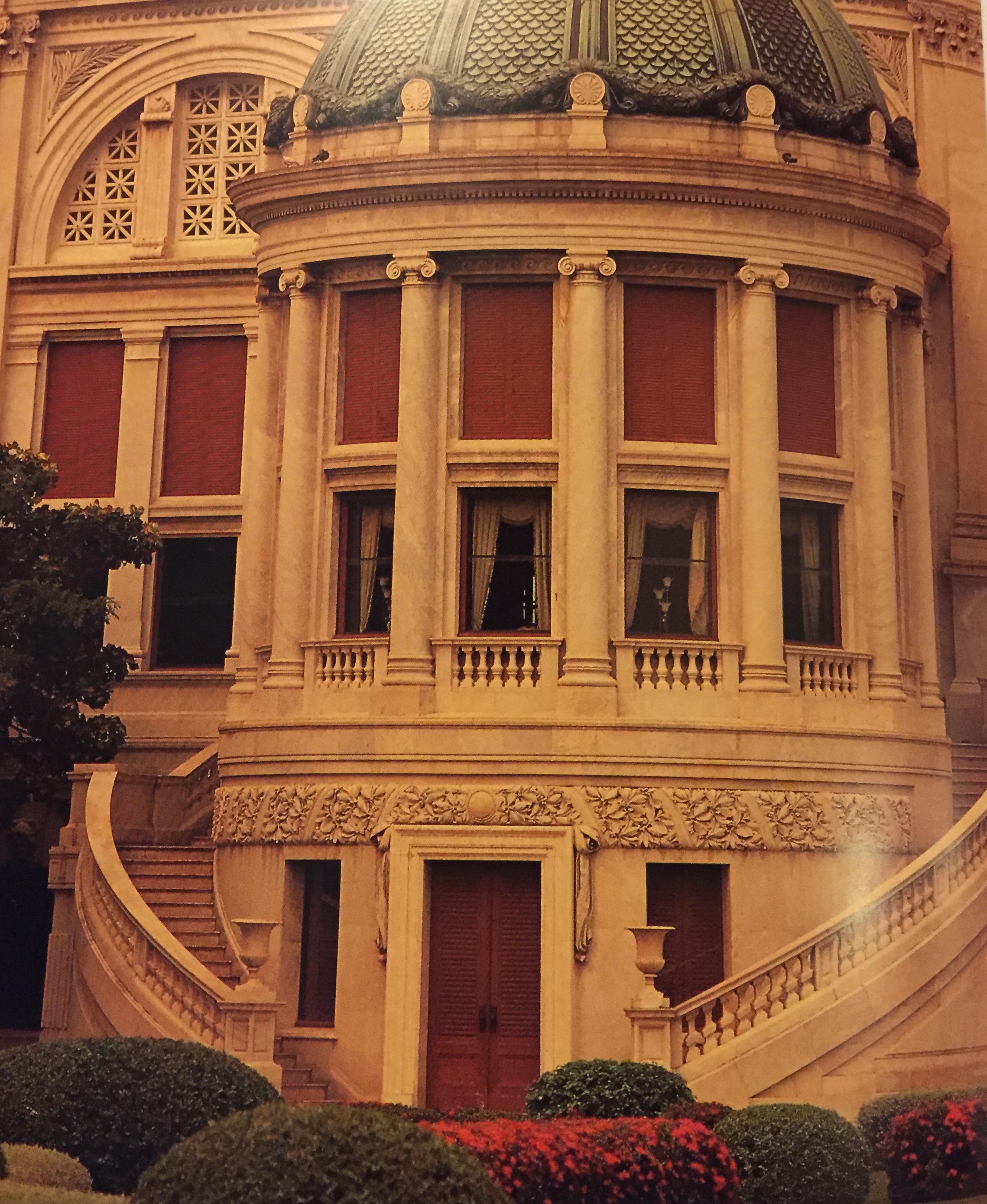

In addition to his individual works on projects for private corporations and the government of Siam, Tamagno often collaborated with other notable Italian architects and engineers. The Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall (1907-1909) was an early collaboration between Tamagno, fellow Albertina Academy graduate Annibale Rigotti, and Italian born engineer Carlo Allegri. Another project was Villa Norasingh, today used as the Office of the Prime Minister of Thailand. Together with Rigotti, and fellow Italians Ercole Manfredi and Cesare Ferro, the men were charged with designing Villa Norasingh as a Siamese version of the famous Cà d’Oro of Venice, giving Bangkok, with its many canals, the feel of a “Venice of the East” in 1923.[5] Tamagno’s works in Thailand reflect the influence of his Italian heritage, often incorporating Siamese design motifs, while overcoming the challenges of building monumental works in a tropical climate.

It is within the context of the work he did on various royal projects that the commission for the Neilson Hays Library falls. Though not a royal work, it remains one of Tamagno’s most unique private commissions in Bangkok.

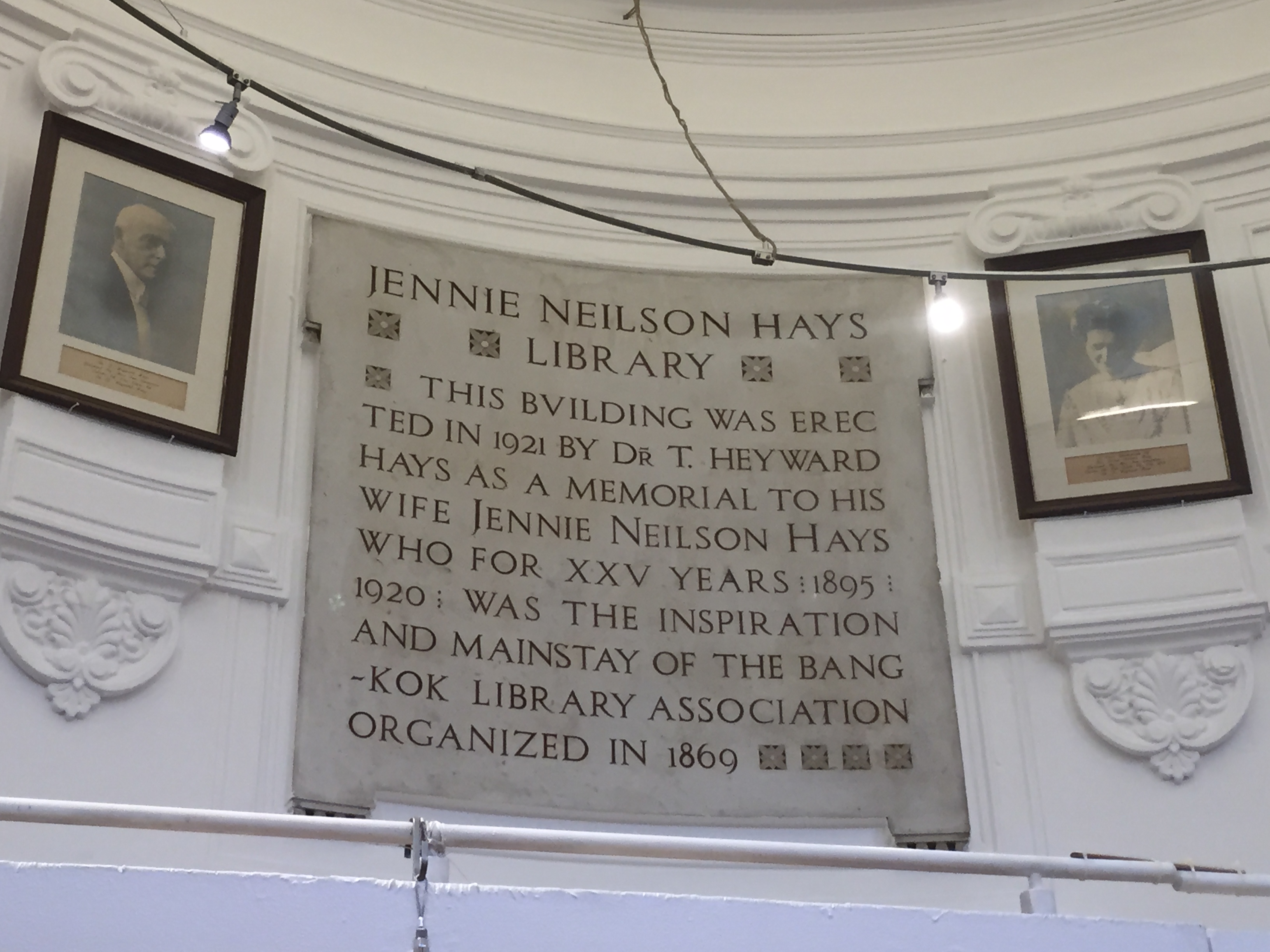

Heralded as “… a grand palace on a small scale” by the Bangkok Post in 1922, the Neilson Hays Library was built in memory of a Danish-American missionary, Mrs. Jennie Neilson Hays, wife of Presbyterian medical missionary Dr. Thomas Heyward Hays. In 1881 Ms. Neilson arrived in Bangkok on assignment with the Protestant Mission in Petchaburi. [6] It was while working with the Mission that she met and married fellow American missionary surgeon, Dr. Hays, in 1887. [7] The pair provided medical care in Bangkok during the course of their married life together in Thailand. From the time of her election as President of The Ladies Library Association in 1895 until her sudden death in April 1920 from cholera, Jennie Hays remained an active member and staunch supporter of the first English library in Thailand. [8] As part of her lasting legacy, in her will she left money to the Library Association, effectively cancelling all their debts. [9] Two years later, on June 20 1922, the present library building, designed by Tamagno and located on Surawong Road, opened to its doors to members, a gift of Dr. Hays to the Library Association. [10] The building is a tender memorial to Jennie Neilson Hays and her dedication of service to the Library Association.

Upon opening, a review of the library and its special design features appeared in Bangkok Post and reads as follows:

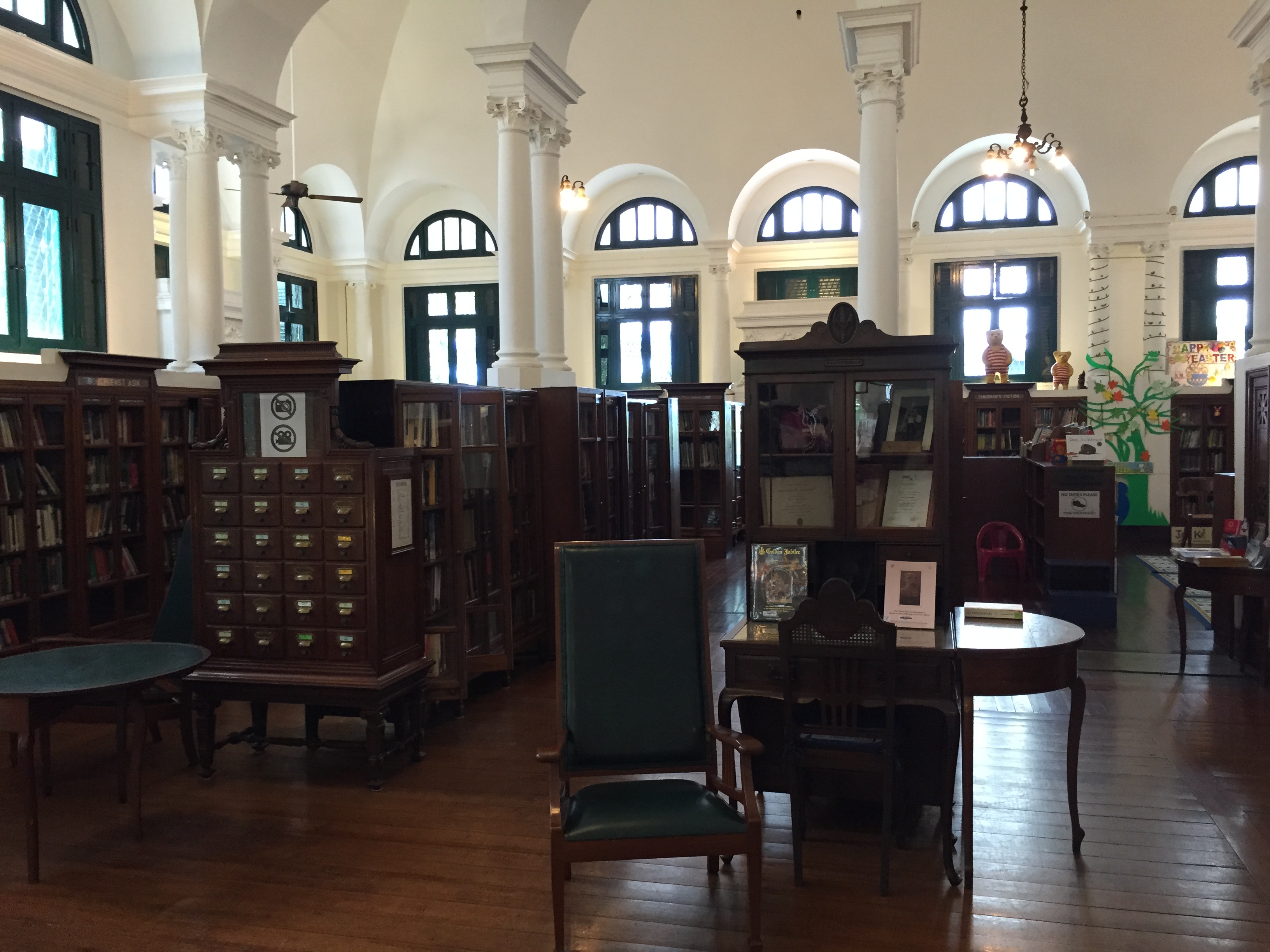

“The design is particularly pleasing to the eye and from the point of view of utility, it would be difficult to find a more ingeniously designed building in Bangkok. From the brass screws in the bookcases to the top roof tile(s) everything is the best that money can buy – material and craftsmanship. The main features of the building are the central hall with its high domed roof, and the two wings also with domed roofs.” [11]

Another description of the library includes further detail into the architect’s overall vision for the building given its location in an area of Bangkok prone to flooding:

“Built on a concrete foundation resembling an inverted saucer, the building is moisture proof and well ventilated. Each of the three large rooms is skirted by bookcases snugly built in double walls allowing an air space at the back, thus keeping them dry and at the same time insect proof. The floors are of polished teak, making the building eminently suited for social functions, and an excellent lighting system has been installed… And there is accommodation for over 8,000 books.” [12]

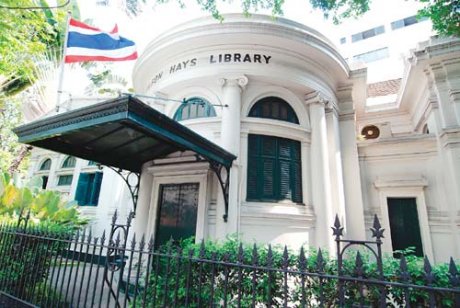

When first arriving at the Neilson Hays Library, visitors enter the library from the side of the building. Architectural pilasters rising the full height of the building are capped with decorative capitals of no specific order, while on the exterior of the rotunda (the former entrance to the library from Surawong Road) four plain-shafted half columns with Ionic capitals attached to the walls. A plain architrave runs around the exterior walls of the building, with arched windows over rectangular ones providing natural light to illuminate the interior from all sides of the building. The distinctive green shutters on the lower windows both darken and cool the interior of the building when necessary.

The interior of the library continues the classical motif seen on the exterior, with freestanding double columns capped with combined Ionic-Corinthian capitals supporting a plain architrave springing point of the vaulted ceiling. Carved garlands are swagged across all the door lintels, apart from the original front doorway in the rotunda, bringing a subtle feminine feel to the otherwise solemn look of the interior. As mentioned in the Bangkok Post description above, the dark hardwood floors and built-in wooden bookcases with glass doors are still in use today. Their subtle design gives the interior the look of a small collegiate library.

Tamagno did not have to look far afield for inspiration when it came to the design of the library. It incorporates many of Tamagno’s design features from other projects on an intimate, personal scale. The library interior recalls Hua Lamphong’s double columned façade while the protruding Rotunda of the Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall is directly referenced on a more intimate scale in the Neilson Hays Library version of the same. Certainly the organic beauty found in the buildings of the Royal Albertina Academy in Turin would have been an influence intrinsic to Tamagno given the amount of time he spent working there before he moved to Bangkok.

With its stately beauty and meticulous attention to detail, the classic Beaux Arts style library remains a lasting memorial of a profound love between a husband and his late wife. Tamagno’s design sensitively captures that feeling of love and devotion. The Neilson Hays Library is a reposeful oasis for its members and visitors who seek a peaceful literary refuge in a majestic architectural setting, unlike anything else in the City of Angels.

Notes:

[1] Leopoldo Ferri De Lazara, Paolo Piazzardi and Alberto Cassio. Italiani alla Corte del Siam–Italians at the Court of Siam, Bangkok: Amarin Publishing, 1996, 218.

[2] De Lazara et al., 218

[3] De Lazara et al., 218-9

[4] Tamagno designed a Siamese Pavilion for the San Francisco Exhibition in 1914. De Lazara et al., 222

[5] De Lazara, et al., 101

[6] Rita Ringis et al., The Neilson Hays Library Bangkok, Tenth Cycle Commemoration Booklet, Bangkok, 1989, 20

[7] Jim Algie, Dennis Gray, Nicholas Grossman, Jeff Hodson, Robert Horn, and Weslet Hu. Americans in Thailand. Singapore, 2014, 100.

[8] Ringis et al., 25

[9] Ringis et al., 25

[10] Ringis et al., 26

[11] Ringis et al., 27

[12] Ringis et al., 28