By Catherine Clover –

“Remember gentlemen, it’s not just France we are fighting for, it’s champagne!”

– Winston Churchill, WWII

As the year 2014 comes to a close, it is a most fitting time to reflect upon the year in review and prepare resolutions for the year ahead. After meeting Francois Hurtel, champagne specialist with Moët Hennessy USA, in the cave at the wine merchant Alex Bernard’s Vineyard Gate in California, I was reminded of why the holiday season is the perfect time to taste and toast the year end with your favorite vintage of sparkling wine. We’re ready to consume the above champagne photographed here! But the persistent question remains, what makes the magic of the bubbles?

In a recent article entitled “Work by chemistry and physics becomes all about the bubbles” published in The Columbus Dispatch on December 28 2014, journalist Laura Arenschield garnered the the input of Gerard Liger-Belair, a French scientist, Andrew Waterhouse, a wine chemist at the University of California-Davis and Dr. Patrick Hunt an archaeologist at Stanford University to help demystify the science behind a glass of bubbly.

“The fermentation process converts sugar to alcohol and carbon dioxide,” said Andrew Waterhouse, a wine chemist at the University of California-Davis. Champagne starts with grapes that are slightly less sweet than traditional wine grapes. They are crushed and made into a wine in which small amounts of yeast and sugar are added. The yeast consumes the sugar, breaking down sugar molecules into molecules of ethanol and carbon dioxide. The result is bubbles.”

Providing the proper historical timeline for champagne production and storage reveals that consumption of sparkling wine occurred over the course of the past two millennia. In an article published in Stanford’s Philolog in January 2011, Hunt summarizes the history of champagne in a concise manner. He points out that the earliest effervescent wine consumed by the Romans was likely not a product of years of oenologic study, but rather a by-product of fermentation process which happened to produce the effect of spumante.

In the same article Hunt clarifies this effect on the Roman vessels that contained the wine even further:

“The natural yeast’s carbonation produced undesirable results for centuries, including bursting bottles, since the cold French winters halted fermentation and warmer spring kick-started refermentation again. It was touch-and-go until stronger bottles were specially made to withstand the internal pressure… That the Romans were in and around Reims is clear from the chalk mines that now comprise some of Pommery’s and others’ champagne caves converted from chalk pits called crayères around 30 meters (about 100 feet) underground.”

Hunt notes some of the science behind champagne and humorously also describes the “fizzics” of bubbles. His champagne article includes a brief history of the introduction of French champagne into French royal courts and English society.

“As tastes changed after the sparkling wine from the region of Champagne was introduced at the Louis XIV’s Versailles court by Marquis de Sillery, it was the exiled Marquis Charles de St-Évremond who seems to have presented champagne to London around 1662. Christopher Merret had even read a paper in 1662 before the Royal Society in London about how to make sparkling wine. Since our London-based historian daughter had introduced us to Tilar Mazzeo’s recent book The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It (Harper, 2008), our family duly trooped in pilgrimage through the countryside to Madame Clicquot’s neo-Gothic chateau in Boursault overlooking the Marne, where she retired after almost single-handedly building the supply and demand global champagne market by 1840, making it an elegant commodity by her merchandising genius. Thanks to Veuve (“Widow”) Clicquot (née Barbe Nicole Ponsardin), champagne today is a status beverage whose orderly bubbles confer even more elegance on grand ladies, especially the ambience of an excellent champagne.”

With roots deeply planted in the wine trade of the early to mid-eighteenth century Champagne region of France, the name Moët is synonymous with a lineage of high quality champagnes. According to the company, by 1743 the champagnes of Moët were exported to many European countries including the UK, Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Holland, Germany and Switzerland. In 1760 Moët was the preferred champagne of the Imperial Court in Russia as well as those members of the French court in the circle of the Marquise de Pompadour. Today the house of Moët remains the official supplier to the Royal Courts of Great-Britain, Denmark, Sweden, Belgium, Spain and the Vatican. Theirs is a heritage of quality and taste unparalleled by any other champagne house.

There are many ways to consume champagne, as a brunch elixir when mixed with different juices, as an aperitif with hors d’oeuvres, as a cocktail mixed with cognac, bitters and sugar and of course, neat. Drinking vessels vary depending on the drinker, some prefer the modern champagne flute, a glass designed to give the drinker the full range of tastes and aromas the champagne imparts. Others prefer the classic saucer shaped glass that is lovely to hold in the hand and feel the release of effervescent bubbles as they escape to the rim. Champagne makes a celebratory statement unlike any other. When sea faring vessels are launched into service it is the bottle of champagne that is sacrificed to commemorate the moment. Similarly, after many sporting events the winner of the match is handed a bottle, or magnum, of champagne, which invariably becomes a token of the win and is used to literally shower the winner and their retinue with a spray of the fizzy nectar.

During my visit with M. Hurtel, I asked him a few questions about the champagnes of Moët & Chandon, and he regaled me with many interesting details, some of which I shall add here. When it comes to the champagnes produced under the Moët & Chandon label, centuries of experience in oenology have helped create the consistent taste the label is so respected for today. With over 2,800 acres of vineyards in Champagne at their disposal of which fifty percent are Grand Cru and twenty-five percent are Premier Cru it is little wonder that they produce such a variety of unparalleled champagnes. It is the long aging in the barrel (24 months no less!) that helps the Moët & Chandon Imperial champagne release its characteristic bright fruitiness with a delicate bubble and silky texture upon the palette.

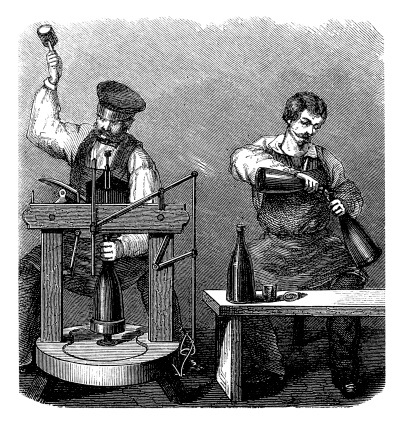

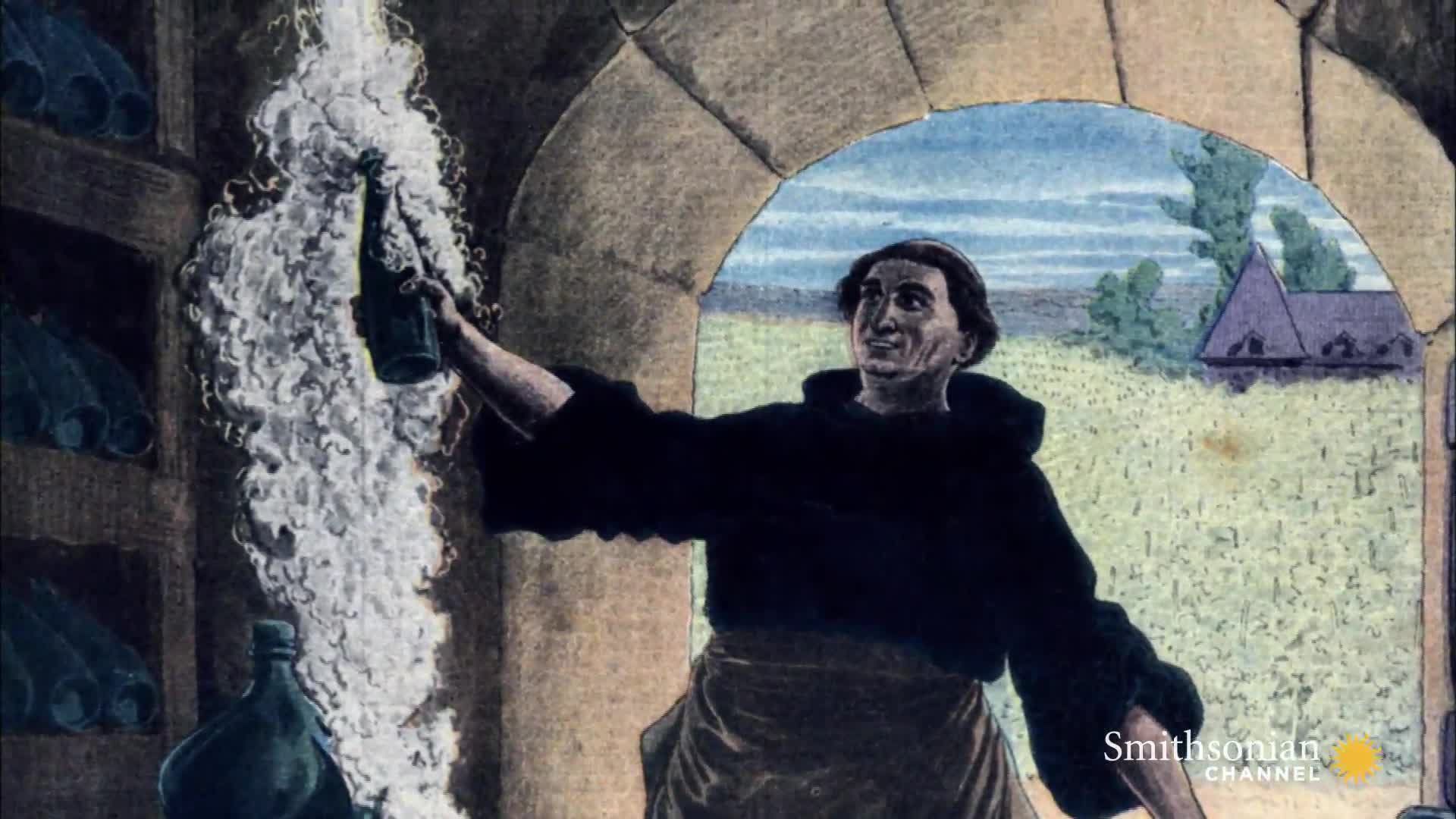

The legendary Dom Perignon label is now one of Moët & Chandon’s most iconic champagnes. The 17th century monk Dom Perignon, considered one of several pioneers in refining champagne by managing to control the process so less bottles would burst – making thicker glass bottles, working to fix the cork with a wire cage, and adding a deep punt in the base for pressure resistance – is reputed to have said when he first tasted his successful end product, “Brothers, come quickly, I am tasting stars!”

Apropos of Winston Churchill’s affection for bubbly, he is reported as having consumed thousands of bottles in his lifetime, possibly one per diem in his adult life. Whether or not these were solo bibendary experiences is hard to know, but he had an indomitable spirit and was always looking for the bright side. Perhaps champagne inspired him as it has so many to likewise celebrate with it.

On December 31 around the world – from San Francisco to Tokyo to Bangkok – the sun will set, the lights will darken and the night sky will fill with a blanket of stars. Fireworks will rain their sparkling lights of celebration over people of all cultures at this joyous time. Though the new year is observed in many different ways, at restaurants, in homes, at parties in small towns and large, there is one thing that will commemorate them all. The familiar ‘pop’ of the champagne cork as it makes its providential flight to free the bubbles and toast the night.