By Patrick Hunt –

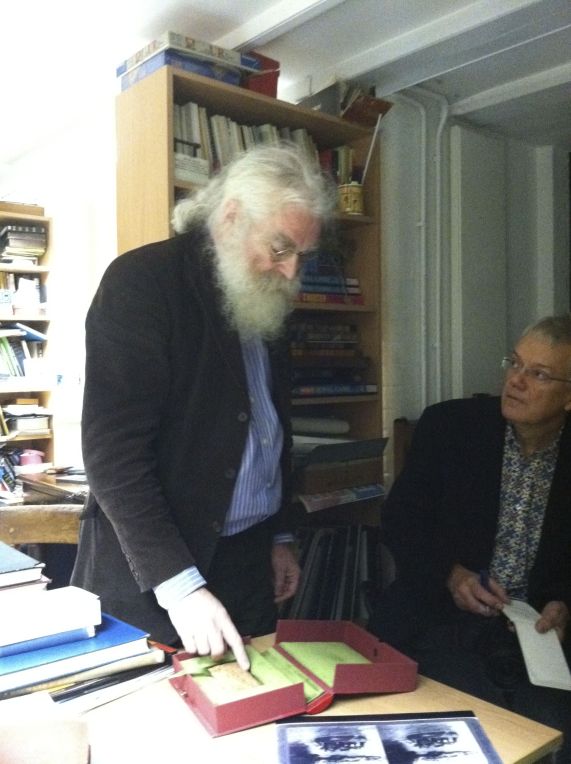

The Atrahasis Flood Tablet I first saw in Irving Finkel’s office at the British Museum a few years ago before this book was published seemed much like many others in the museum galleries, a cuneiform clay tablet one could easily hold in a hand. But this one was different in several ways once Finkel had started translating it from the cuneiform, rightly relishing his discoveries. For one, it described a round ark built for the great flood – like a giant coracle – and the second stunning revelation was one phrase a delighted Finkel had repeated with amused intensity: the animals assembled for the menagerie to be safely protected from the deluge were to enter the ark “two by two”, exactly as the biblical account said. This had been recorded by Israelite scribes thousands of years ago but written down seeming millennia later than this other earlier Mesopotamian account in front of me in clay. The “two by two” meme was the origin of the biblical Noah story, Finkel told me, and showed how carefully some vital details are repeated, completely logical if you want to replicate a species from haploid DNA.

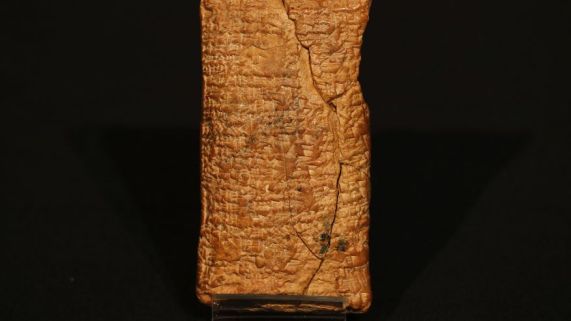

The unassuming cuneiform tablet that launched this marvelous book is only sixty lines long and measures a compact 11.5 by 6.0 cm (4.3 x 2.3 in), written down almost 4,000 years ago, roughly 1900-1700 BCE in literary Babylonian (essentially Akkadian). It tells very pragmatically how to build the Ark, describing the local materials, including rushes, ropes, bitumen and tamarisk wood, and the circular dimensions, such as its diameter equalled 70 meters or 22 London double-decker buses end to end. Thus Finkel’s translation of the “new’ Atrahasis Ark Tablet shows a “Super Coracle” with a base area of 3600 square meters and a divinely-shared plan from the god Enki to be drawn out in a circle (kippatu in Akkadian) on the ground.

Some of the “new” details brought out in this particular Atrahasis tablet (there are others) are fascinating. For example, among the many animals to be brought, aboard, the list includes 44 types of snakes, 19 types of dogs, 13 types of insects with three added types of locusts differentiated by size, 16 types of larvae, 5 types of lizards, 3 types of jackals, 11 types of scorpions, and 20 types of lions, all reflecting a genuinely Mesopotamian world of the time. Perhaps the one startling animal genre is that 23 ties of pigs are to be shipped, intriguing given later religious bans.

Finkel’s writing is wonderful. Here’s an example excerpted from the first chapter:

“…George Smith’s discoveries led to unease in more than one quarter. It was simply bizarre that a close relative of Holy Writ should emanate from such a primitive, barbarous world through so improbable a medium, to thrust itself uncompromisingly into public consciousness. How could Noah and his Ark possibly have been known and important to the Assyrians of noble Asnapper and the Babylonians of mad, dread Nebuchadnezzar? Worried people over garden fences and in church pews clamoured to have important questions answered. Smith, writing soberly in 1875, ducked none of them, unanswerable though they were. Two questions that have presented themselves at the outset have echoed ever since:

Which flood translation was older? When and how did the transmission of the flood tradition take place?

The first has long been answered: cuneiform flood literature is by a millennium the older of the two, however one dates the biblical text – still a difficult problem. As for the second, this book offers a new answer…”

Finkel also convincingly relates – seemingly as a pioneer – how the exiled Jews in their Babylonian Captivity in the late seventh to sixth centuries BCE heard the Flood story and their scribes eventually acquired cuneiform reading skills to absorb and recycle the scribal details for their own Torah, to be handed down as the familiar Genesis 6-9 story of Noah.

It’s very hard to stop reading when one writes like this.

Finkel is a great storyteller, savoring details with wit and verve, and his droll sense of humor catches the reader immediately, from describing the early training of a budding cuneiform scholar to the antics of George Smith, a pioneer cuneiform Assyriologist in this very museum and thus a predecessor of Finkel more than a century ago. As patient as he is meticulous (without being boring) Finkel takes the history of the Noah story back to a time much earlier than its familiar Hebrew account. He has spent enough time in the field to know rural reedy coracles still cross the Euphrates into the present time, and from his many translations of texts – he can unlock cuneiform and read it as quickly as most authors read the New York Review of Books – can also make the dimensions and philology of this literary ark version easily accessible.

Finkel also gives early on in the book to anyone interested a compelling basic introduction to cuneiform writing from the origin of wedge-shaped signs to the Mesopotamian syllabaries and how Sumerian differed from later Akkadian, the precursor to many cognate Semitic languages such as Babylonian, Assyrian, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Hebrew and even Arabic that subsequently evolved however differently.

I was in Istanbul this past spring and saw in many of its old bazaars various Safavid Persian, Mughal and Ottoman hand-painted illuminations of the Flood story. Animals of all kinds peeked from windows under turbanned mariners of a bearded old sage and his three sons (like the aged Noah and his sons Shem, Japheth and Ham); the ships were often gilded and floated on the waves en route to a salvific destiny. The tale also regales Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the great Abrahamic faiths. But the pre-Abrahamic story of the Flood and its savior – however told or depicted – belongs to the world, not just to any one people or religion. In this case the Flood epic precedes the later religions of the fierce desert, going back to Sumeria, to Gilgamesh’s Utnapishtim and the Akkadian of the Early Bronze Age more than four thousand years ago as well as the Babylonian of about the time of Hammurabi, as Finkel tells better than anyone with the Atrahasis Tablet.

I assigned Finkel’s new book to a Stanford University class this past quarter on Mesopotamia, and the class agreed it was a keeper, extremely well-written and full of irony. If an academic can write a page-turner, this is it.