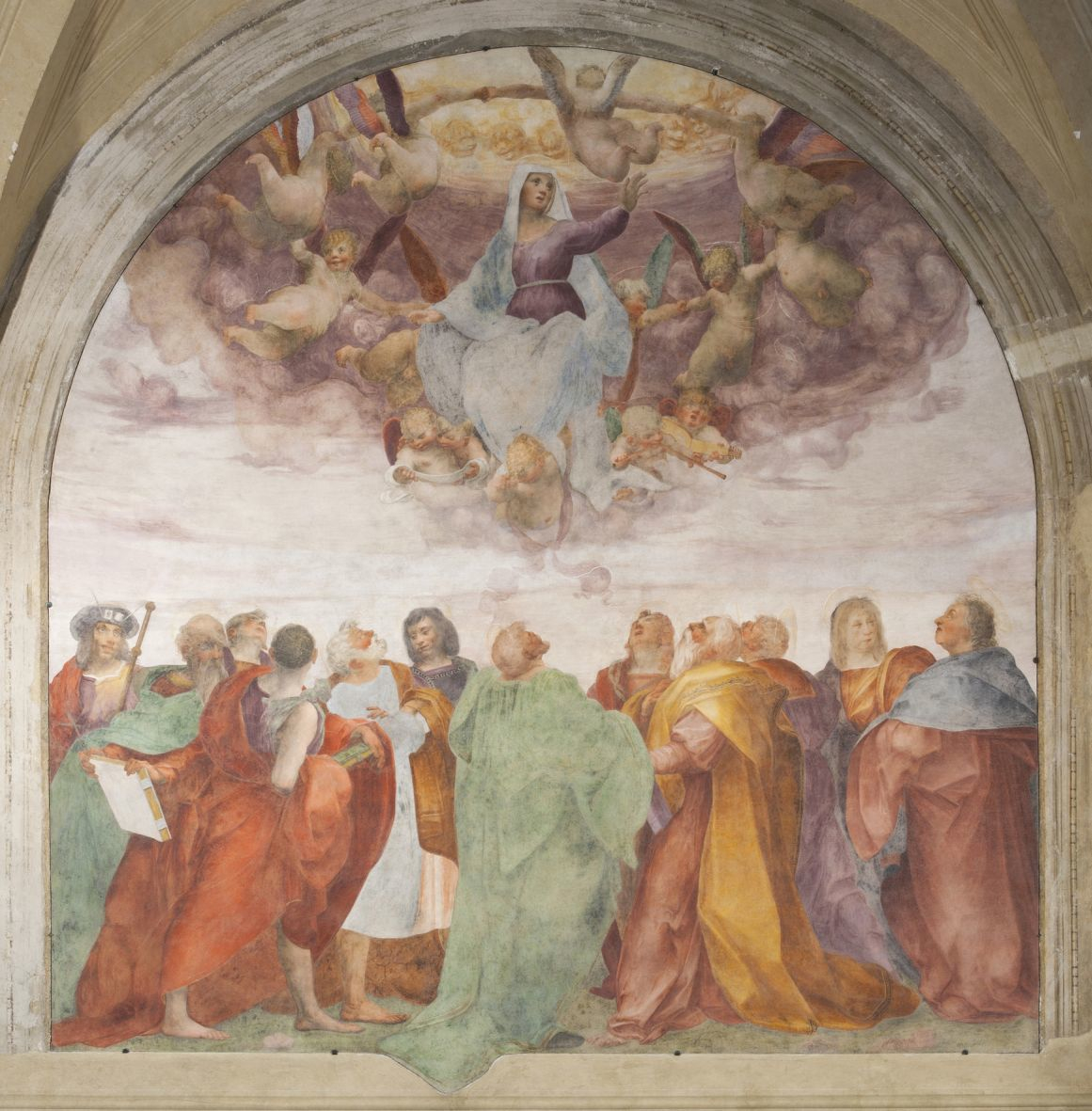

By Andrea Gáldy – Pontormo and Rosso. Diverging Paths of Mannerism, 8 March to 20 July 2014, Palazzo Strozzi, Piazza Strozzi, Florence, Italy, www.palazzostrozzi.org. An exhibition curated by Antonio Natali (director of the Uffizi Gallery) and Carlo Falciani (lecturer in art history) and held at the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi. Carlo Falciani and Antonio Natali, eds. Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, Diverging Paths of Mannerism. Mandragora: Florence, 2014. Paperback, pp. 371, 129 illustrations (in b/w and colour). “Mannerism” is a problematic term: invented quite recently as a label for art created between the Sack of Rome 1527 and the advent of the Baroque, it covers one of those awkward time periods which with hindsight and from a distance of several centuries seem to belong neither with the preceding nor with the following eras. Such a point of view has much to do with the nineteenth-century definition of the “Renaissance”, another highly problematic term, as the rebirth of Classical Antiquity in Italy, mainly Florence. Accordingly, mannerist art was created by followers of Michelangelo without ever reaching the genius of their hero and model; the label was often used derogatorily in the past – almost to denote a bad Renaissance following the good Renaissance of Masaccio, Donatello and Michelangelo. No longer the rebirth of Antiquity, Mannerism was defined as an era of the strange and fanciful, art created by busy entrepreneurs without real talent, epigones such as Giorgio Vasari, or weird eccentrics with an unfortunate tendency towards eating disorder and heresy, such as Jacopo Pontormo. Art historians have been hard at work to dispel these notions and exhibitions such as the current show at Palazzo Strozzi contribute to a much more nuanced view of a style which developed as an organic part of the innovations which had been gradually introduced by artists since the thirteenth century. Some of these were the result of the artistic engagement with and changing intellectual perception of antiquities; others had to do with technical progress, access to a larger range and better quality of raw materials, a growing financial surplus which could be re-invested in artistic production. Foreign influences sparked creativity in Italy while Italian know-how was received and adapted to the requirements of fellow-artists across Europe. By the sixteenth century, the art world – just like warfare – had become international and an integral part of the cosmopolitan Europe of princely courts. Artists as well as their patrons were engaged in more or less friendly rivalry and, therefore, had to seek attention through the beauty, novelty and virtuosity of their art. Rosso Fiorentino and Pontormo were part of this world. Born in 1494 in and near Florence respectively, both worked with Andrea del Sarto in the Chiostrino dei voti of Santissima Annunziata (Figs. 1.1-3; cat. I.1.1.-3.). While Pontormo (Jacopo Carrucci, d. 1557) remained in the Florence area for his entire life, Rosso (Giovan Battista di Jacopo, d. 1540) led an itinerant existence which brought him eventually to the royal court of France. Whereas Pontormo found early patronage with the Medici (95-101), Rosso was favoured by leading families of the Florentine oligarchy engaged in a losing battle to preserve the Republic. In the end both artists worked for aristocratic courts, for these were the main source for commissions, and therefore it is perhaps not so fruitful to style the one a court painter for the Medici and consider the other the rebel artist in the Savonarolan tradition. As so often in these matters it is important to be able to study and compare the works of art carefully in the historical context of a precise chronology.

By the time the two artists worked alongside one another in the Chiostrino, the Medici had been involved with Florentine politics for a couple of centuries. We all too often regard this family as the natural rulers of Florence, when their political hold on the city-state was precarious well into the sixteenth century and the single branches of the clan were quite happy to fight one another as well as compete with the other leading families of Florence. Even though the Medici were enjoying a political comeback from the 1510s onwards, there was constant opposition and infighting; we cannot speak of a Medici court before the 1530s and even then the ducal grip on power over Florence might have ended on several occasions in the 1540s and 50s. Cosimo I’s survival was ever a close run thing as is attested by episodes of open rebellion, intrigues and conspiracies during his rule. What the exhibition (and the XI chapters of the catalogue composed by an international group of scholars) does best, in my view, is to trace the artistic development of the two artists side by side – and, it will take a long time before we shall have such an opportunity to compare their work in this fullness and well-choreographed juxtaposition. Of course, both painters were influenced by the oeuvre of their teachers and role models, which in Pontormo’s case were mostly Florentine and in Rosso’s include a wider variety of regional and personal styles.

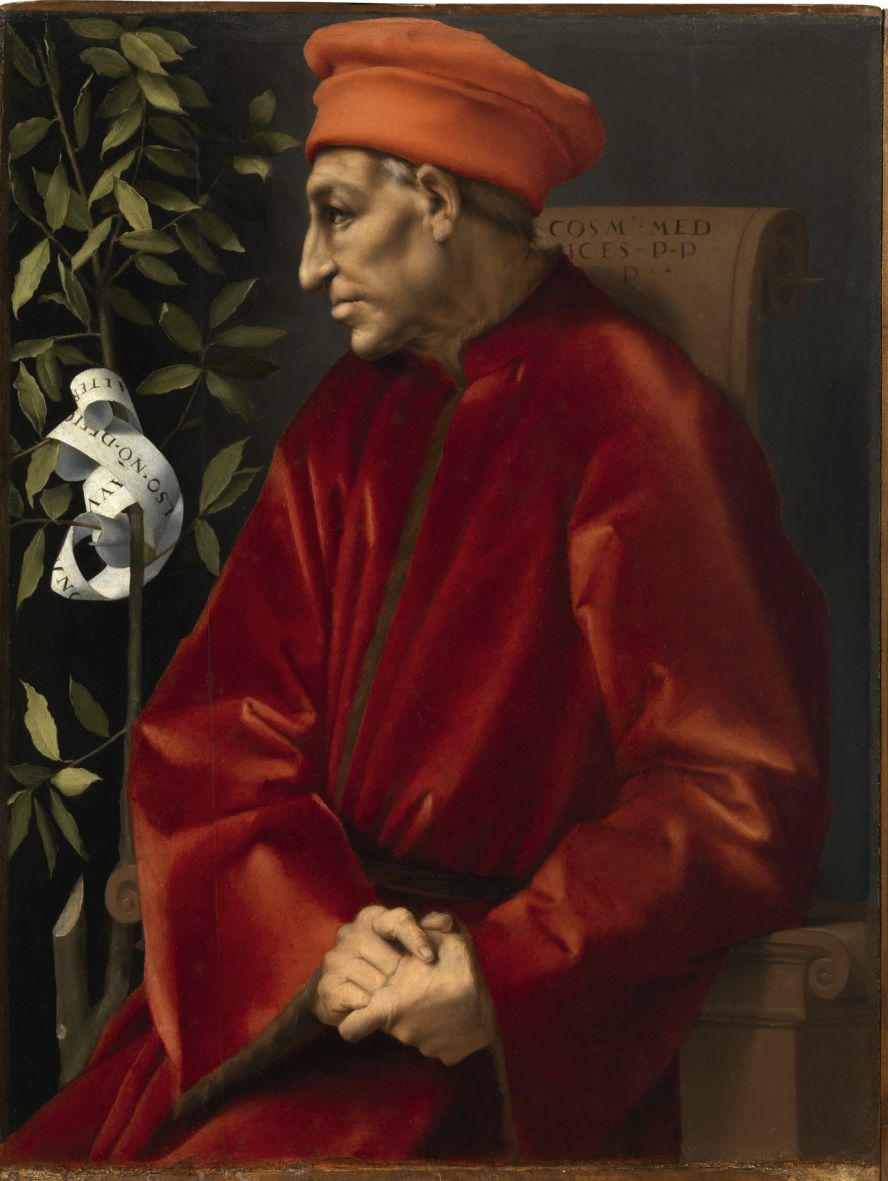

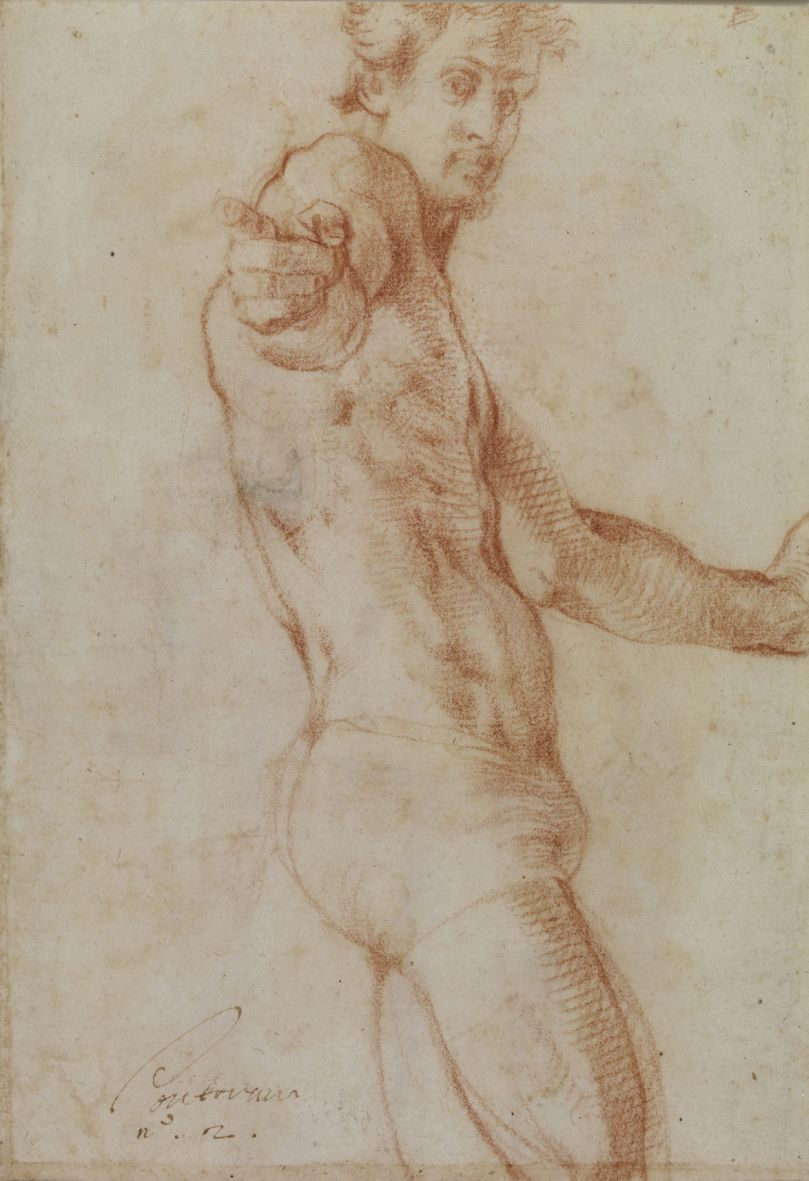

At first glance, Pontormo’s work seems to have been more static in comparison to the wildly experimental Rosso; such a view could, however, be explained by the fact that Pontormo supposedly found his visual language, a personal style which satisfied him and pleased his patrons, early during his career. Variations on composition, light and colour kept his creations fresh and interesting as did veiled allusions to classical sculpture in the Pucci altarpiece (Fig. 2; cat. II.2.) and the subtle subversion of the rules of good painting as defined by Alberti during the previous century. Pontormo’s drawings, in particular, are full of verve and movement, for example his self-portrait (Fig. 3) at the British Museum. Rosso, by contrast, left Florence (85-93) at the time when Medici fortunes were at a low ebb, when Pontormo was commissioned to paint the defiant, posthumous portrait of Cosimo the Elder now at the Uffizi (Fig. 4; cat. IV.1.2.), and when a young boy received the programmatic name of Cosimo together with the hopes and ambitions of an entire family.

One may well debate whether Rosso’s or Pontormo’s manner was more modern, sweet, natural or well-grounded in disegno (159-187). As the exhibition makes clear from the very first section, both could do harsh as well as smooth. Rosso’s portraits, altarpieces and all’antica compositions (Fig. 5) looked back to the Florentine Quattrocento and to Roman Antiquity as much as they looked north to Trans-Alpine art for inspiration (191-227). It is the symbiosis of these diverse influences which made the two artists’ respective creations new and interesting and thus attractive to a (courtly) audience always under peer pressure to commission what their competitors could not have. For Duke Cosimo (b. 1519, r. 1537 to 1564) it made additional good sense to choose Pontormo for a number of commissions, since such a modus operandi was in line with family tradition and thus something he is known to have revived as part of his own cultural politics. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that Pontormo was not the only artist working for the Medici dukes and that Rosso found employment with a wide range of patrons keen to attract the services of Italian masters able to create work at the highest level.

The uncertainty of a post-reformation world in combination with the shock of the Sack of Rome have traditionally been made responsible for sending sixteenth-century artists over the edge into the arms of Mannerism. Certainly, during the first half of the sixteenth century ground-breaking political, religious, intellectual, societal and dynastic changes took place; it would be strange if they remained without influence on European cultural life and artistic production. Nonetheless, it would also be rash to postulate a separate new style, to a large extent represented by artists not even present in Rome during the cruel events of 1527. As reason suggests and the exhibition amply demonstrates, there was no obvious break in artistic development. Experimentation on the basis of previous achievements was going to point the way towards a modern manner. No wonder that, as far as we can tell, Rosso and Pontormo did not regard themselves or their colleagues as representatives of a new art but as the heirs of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Andrea del Sarto.