By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Archbishop Antonio Agustín y Albanel (1517-1586) died on 31 May 1586 at Tarragona, a city of notable traditions both as the Roman capital of Hispania Citerior, then Hispania Tarraconensis and as the seat of one of the oldest archdioceses in Spain, established even before the martyrdom of Bishop St. Fructuosus in the third century AD. Numerous Roman monuments as well as Roman and Phoenician inscriptions survive, even though the ancient remains were used as quarries over the centuries, in particular the amphitheatre.

Agustín was buried in the Tarragonese Cathedral which rests on the site of a Roman temple. His tomb bears the inscription: ‘Vixit Annis LXX. M. III. D. III. obiit damno publico pridie Kalendas Junias MDLXXXVI’ (his age is given incorrectly). André Schott SJ, the learned Latinist and Graecist who also taught in Zaragoza and Toledo, held the Oratio at the funeral, later published at Antwerp, in which he celebrated the late clergyman and antiquarian. The archbishop’s rich library, consisting of 561 manuscripts and printed books listed in a surviving catalogue, was bought by Philip II from Agustín’s heirs for the Escorial. Today Agustín is perhaps most famous as an antiquarian and numismatist. His Dialogos de medallas, inscriciones, y otras antiguedades were completed before his death to be published in Spanish in 1587. Two posthumous Italian translations came out in 1592. [1]

Born in Zaragoza on 26 February 1517, Agustín came from families of lawyers on both sides of his parents. [2] His father became vice-chancellor of the kingdom of Aragon. The young man had continued family tradition and trained in both Roman and canon law in Spain; he received a doctorate from the University of Salamanca on 10 April 1534. From 1535 he studied at the Spanish College in Bologna with Budé and Alciato and received his doctorate there on 3 June 1541. In 1537, even before the completion of his studies, he was called away to Rome to become Auditor Camerae; he received legal tuition in Padua and Greek instructions from Lazarus Bonamicus. His correspondence attests to an early interest in legal source material and soon publications, for example the Emendationum et opinionum libri IV and Ad Modestinum, enhanced Agustín’s reputation and led to his appointment as Auditor of the Sacred Rota in 1544 (under Pope Paul III).

On their arrival in Rome, Agustín and his friend and secretary Jean Matal quickly grasped the importance of inscriptions for the study of Roman law. They started to collect inscriptions and also emended syllogai already published, for example those in the possession of Cardinals Carpi and Salviati. It seems they often recorded inscriptions as soon as they came out of the ground. Such work put them in touch with antiquarian fellow-enthusiasts from the circle around Cardinal Marcellus Cervini, the future Pope Marcellus II. It also meant constant and immediate contact with the numerous ancient monuments of the eternal city: Agustín and Matal undertook a certain amount of archaeological tourism and during such trips sought to recognise monuments by comparing their ruins to images on ancient coins. [3]

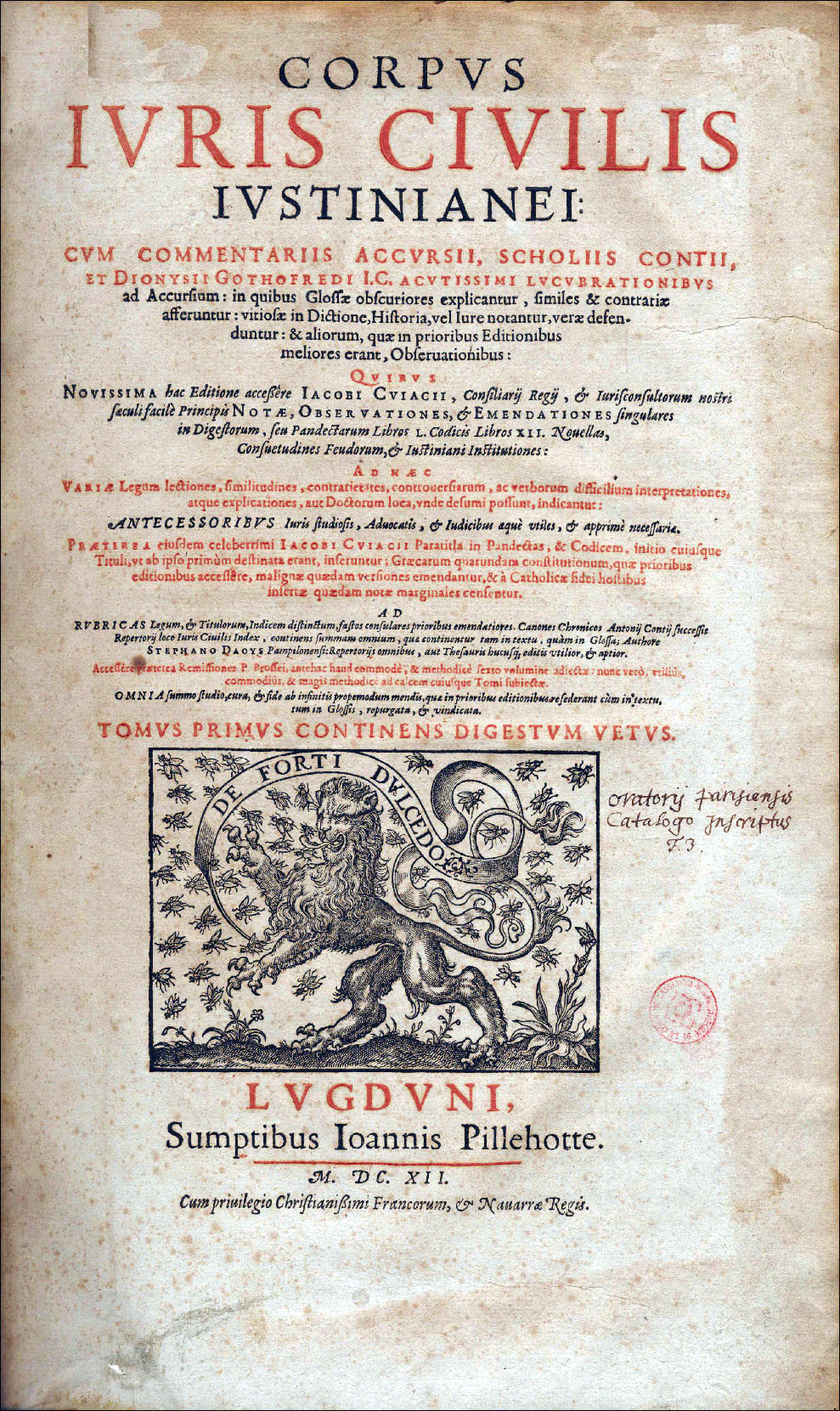

In 1559 Philip II appointed Agustín as Censor of the Spanish Court for Spanish Sicily. Agustín participated at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) before he returned to Spain in 1564, first to Lerida (modern Lleida in Catalonian) – he had been Bishop of Lerida since 1561 – and in 1577 to Tarragona. He continued his scholarly work, maintaining his contacts with Italian colleagues, while preparing the publication of several books. De legibus et senatus consultis was published in 1583 with an introduction and notes by Fulvio Orsini. It contains two indices and is diligently footnoted from ancient authors. At the back reproductions of inscriptions of legal texts on marble and bronze can be found which are rendered as fragments without modern reconstruction. The reader is also informed about who owned these inscriptions at the time of writing.

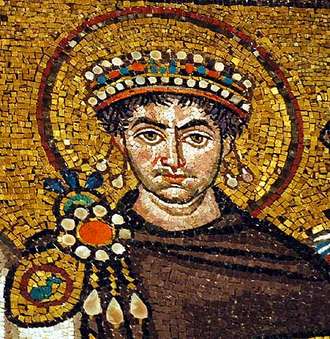

An intriguing episode during Agustín’s early career brought him to the Duchy of Florence from October 1541 to January 1542. The Imperial army had imposed Medici rule on the city ten years earlier and Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici depended on Spanish good will. Spanish troops held the fortresses of his domain, including the Fortezza da Basso in Florence. Antonio Agustín wished to study the famous Florentine manuscript of Justinian’s Digest, the so-called Pandects. This ancient manuscript was most likely executed shortly after 533; it had been taken from the Pisans in 1406 and was kept in the ducal palace (Palazzo Vecchio) at the time. Although the text of the Digest had survived in several copies, one of which was kept in Bologna, Agustín hoped to find in the Florentine copy the uncorrupted master text for all the other versions then in circulation. [4]

When Agustín arrived in Florence, Lelio Torelli, the ducal first secretary, had already started to work on an edition of this important legal text. Other scholars, for example Budé and Alciato had unsuccessfully sought permission to study the valuable manuscript but the young Spanish lawyer was allowed to consult the Pandects for three months. Torelli even seems to have welcomed the interest of his younger colleague, possibly because he was unaware of the transcription of the manuscript executed at great speed by Agustín and Jean Matal. After his return to Bologna Agustín wrote a thank-you letter to Torelli, thus starting a lively correspondence about the Pandects which was going to last until 1553. [5] In June 1542 he wrote to his compatriot Pedro Roiz de Moro, then in Cracow, telling him about his work on the ancient manuscript.

Agustín’s preferential treatment in Florence even included access to Agnolo Poliziano’s manuscript notes made in the late 1400s while studying the Pandects. Eventually, he announced the completion of a first book of Emendations. Torelli who was going to publish his own edition of the text through the ducal press of Torrentino only in 1553 nonetheless continued to be helpful. He arranged for Agustín’s four books of Emendationum, three of which were dedicated to Michele Mai, the secretary of Charles V and ambassador to Rome, later vice-chancellor of Aragon, to be published in Venice in 1543; later reprints of this book in Basel and Lyon contain essays by Torelli.

There is no doubt that the work on the Pandects was regarded as highly important. The author of Cosimo I’s funerary Oratio, Pier Vettori, fellow-antiquarian, friend, and correspondent of Agustín, singled out the collation and publication of the Pandects for particular praise:

Libros Pandectarum collatos cum antiquissimo, & fidelissimo exemplari, diligentia, & studio sapientis senis, ac magni iurisconsulti, quod apud nos tamquam Palladium servatur, infinitis inde mendis sublatis, curavit magnifico excudendos: eximiumque hoc bonum, quo soli fruebamur, voluit commune nobis esse cum omnibus mortalibus.

The Pandects were not the only antiquity in the ducal residences. The Duke had started to collect antiquities almost as soon as he came to power in January 1537. At the time of Agustín’s visit Cosimo’s collection was not yet very rich; nevertheless the Duke had been accused by Florentine rebels for spending state revenue on (supposedly ancient) medals. Enea Vico who was going to visit Florence in 1545, however, mentioned the collection in his Discorsi sopra le medaglie degli antichi divisi in due libri (Venice 1555), drawing attention to the beauty and rarity of the objects displayed.

Agustín may well have been considered as a potential source of antiquities and specialist knowledge by the young duke who was then keen to collect coins, bronzetti and large marble statues from Rome. Cosimo regularly found that not only did his funds not match his appetite for ancient art but that his relationship to the Papal States needed to improve if he wanted to export anticaglie from Rome. Agustín might have been in a position to help. But, perhaps more importantly, the young legal archaeologist was Spanish. So was Cosimo’s wife, Eleonora Alvarez de Toledo, her father Don Pedro, Vice-Roy of Naples, while the Spanish garrison in Florence was under the command of Don Juan de Luna, is mentioned in the introduction of the Emendationum as having been helpful to Agustín. Many of the letters between Cosimo and his father-in-law, Don Pedro di Toledo, mention the problems the young Duke had with the Spanish troops in Florence and how impatiently he sought to be delivered from their occupation. [7] Agustín, whether he was aware of these problems or not, benefited from them by being allowed to pursue his studies on the Digest.

In conclusion, this notable Spanish cleric was not only recognised by the church for his leadership, integrity and administrative abilities but even more beyond ecclesiastic circles for his antiquarian scholarship and detailed contributions to Justinian legal studies and numismatic history.

* Editor’s Comment *

It is perhaps noteworthy that Cosimo I de’ Medici himself – apparently an admirer of Agustín – was the patron founder of the Uffizi in Florence, one of the reasons he is shown on the masthead of our Electrum Magazine as a visionary fascinated by the past. Although the Uffizi spaces were administrative offices first, part of Cosimo’s original plan was that the Uffizi were also to showcase masterpieces from the great Medici collections on the piano nobile, which idea of Florentine display ultimately superseded administrative purposes, an exemplary precedent lasting today for the great good of public collections.

Notes:

[1] Dr. Christ. Ludwig Neuber, Anton Augustin und sein civilistischer Nachlass, Eine Erinnerung an ihn wie an seine Verdienste um das Civilrecht, Berlin 1823, 19-20 and note 37, 23-4; Andreas Schottus, Laudatio funebris V CL Ant Augustini, Archiepiscopi Tarraconensis In qua de vita, scriptisque disseritur: de prefecto item Iurisconsulto, & Episcopo, Antwerp 1586; for the catalogue of books see Felipe Mey, Aeternae memoriae viri Antonii Augustini, Archiepiscopi Tarraconensis, Bibliotheca, graeca manuscripta, latina manuscripta, mixta ex libris editis variarum linguarum, Tarragona 1587; Antonio Agustín, Dialogos de medallas inscriciones y otras antiguedades, ex bibliotheca Ant. Augustini Archiepiscopi Tarraconem, Tarragona 1587, published in Italian as Dialoghi intorno alle medaglie, Italian translation by D.O. Sada, Rome 1592 and Discorsi del Signor Don Antonio Agostini sopra le medaglie et altre anticaglie divisi in XI dialoghi, tradotti dalla lingua spagnola nell’italiana con l’aggiunta di molti ritratti di belle, et rare medaglie, Rome 1592 by Ascanio et Girolamo Donangeli.

[2] E. Duran, ‘Antonio Agustín y su entorno familiar’, Michael H. Crawford and Christopher Ligota (eds.), Antonio Agustín between Renaissance and Counter-Reform, London 1993, 5-19, see 5-7.

[3] Richard Cooper, ‘Epigraphical Research in Rome in the Mid-Sixteenth Century: the Papers of Antonio Agustín and Jean Matal’, Michael H. Crawford and Christopher Ligota (eds.), Antonio Agustín between Renaissance and Counter-Reform, London 1993, 95-111, see 99, 102, 104.

[4] Francis de Zulueta, Don Antonio Agustín (8th lecture on the David Murray Foundation in the University of Glasgow, 14 February 1939), Glasgow 1939, Glasgow University Publications 51; Angelo Maria Bandini, Ragionamento istorico sopra le collazioni delle fiorentine Pandette fatte da Angelo Poliziono sotto gli auspici del Magnifico Lorenzo de’ Medici ora ritrovate e restituite al pubblico a cui una volta appartenevano, Livorno 1762. The Digests manuscript had been in Pisa from ca 1284. According to Cosimo Conti, La prima reggia di Cosimo I, Florence 1893, 197-9, the Pandects were not mentioned in the 1553 inventory because they were at Lelio Torelli’s home. The Digest was usually kept in a dedicated cupboard with a Bible in the Capella dei Priori; Nicolas Barker, ‘Antonio Agustín’s Letter to Diego Hurtado de Mendoza’, Michael H. Crawford and Christopher Ligota (eds.), Antonio Agustín between Renaissance and Counter-Reform, London 1993, 21-9, esp. 24-6, a copy of Agustín’s letter to Mendoza is published as Appendix I, 265-77.

[5] Ms. To. 47, Agustín to Torelli, sent from Bologna to Florence, February 1542; Jean-Louis Ferrary, Correspondence de Lelio Torelli avec Antonio Agustín et Jean Matal 1542-1553, Como 1992 (with bibliography), no 1, 45: see the editor’s comments, 46, note 1, according to whom it was written after Augustin’s and Matal’s return from Florence in early 1542. Agustín began to recommend his compatriots, for example Pedro Ponce (Pedro de la Puente), for office in Florence.

[6] Andrea Gáldy, Cosimo I de’ Medici as Collector: Antiquities and Archaeology in Sixteenth-century Florence. Newcastle, 2009. In 1547 and in 1549 the Ricordanze in the Florentine State Archives describe the Duke’s antiquities as being kept in a cupboard in the room used by the ducal goldsmiths; ASF, GM 14 (fol. 37) and 15 (fol. 144 v.). According to Giovanni Pelli Bencivenni (Saggio istorico della Real Galleria di Firenze, Firenze 1779, I, p. 69) Cosimo I was accused by the fuorusciti at the congress of Nizza in 1538; Enea Vico, Discorsi sopra le medaglie de gli antichi divisi in due libri, Venice 1555, Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari, 6.

[7] Archivio di Stato di Firenze (ASF), Mediceo del Principato (MP), 4068 to 4073.