By Patrick Hunt –

Rembrandt van Rijn lived here in this imposing house on the old Breestraat near the heart of old Amsterdam from 1639-58. Now a museum (Rembrandthuis, “Rembrandt House”) along with the adjacent contemporary structure to the left, survival of this intact 17th c. house is due to Rembrandt’s enduring legacy.

My recent visit in April of this year to Het Rembrandthuis was a highlight of four days in Amsterdam conducting historical and art research before my lecture tour for Scientific American Travel. This small yet important museum is one of Amsterdam’s best treasures, and deserves a much wider audience.

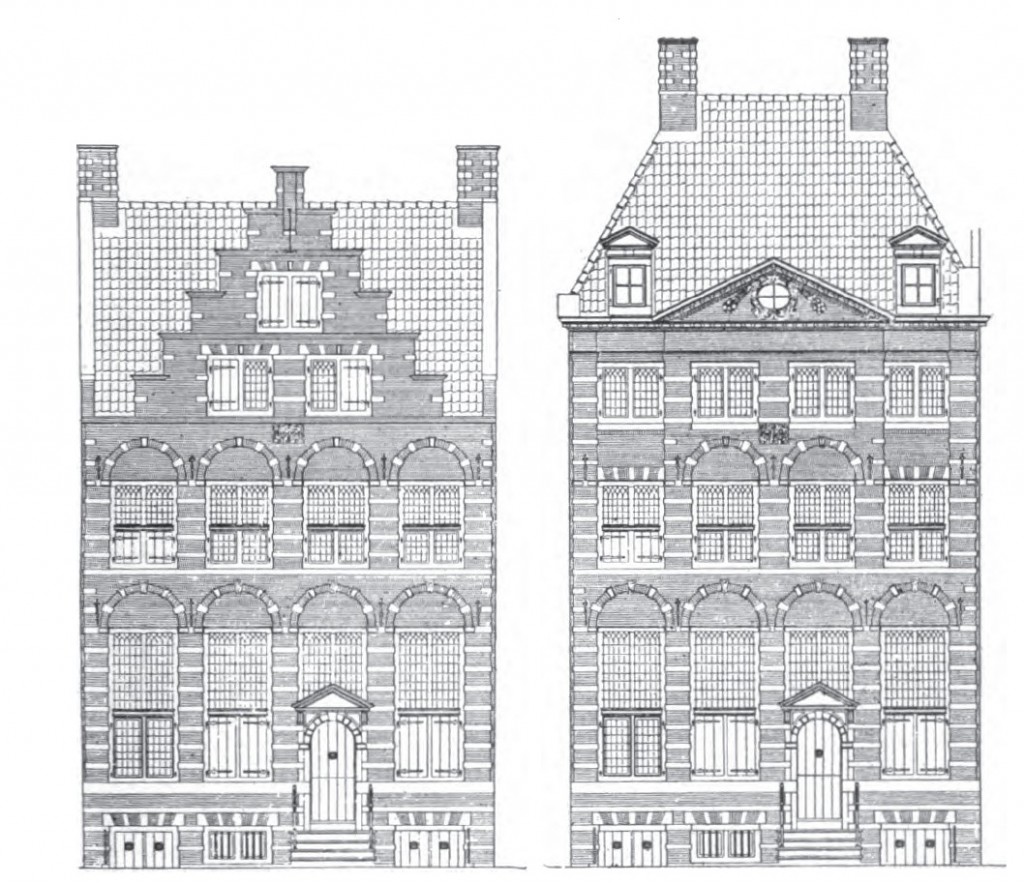

Restoration – researched by historian Henk Zantkuijl – on the original Rembrandt house was completed in 1999 to bring it as close as possible to how it looked in his time, using the 1656 inventory of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy, although a full level story plus attic was added to make it taller some time after he lived in it, as seen in the above image [2]. Architect Maarten Neerincx worked with Zantkuijl and the firm Kneppers and Midreth did the careful restoration. After purchasing the adjacent property, the modern part of the museum next door opened in 1998 after its exterior was designed by architects Moshe Zwarts and Rein Jansma, its interior by Peter Sas.

Purchased by an installment loan in early 1639, with an initial payment of 1200 guilders, the total cost of the expensive house purchase was 13,000 guilders, a substantial sum. Although Rembrandt was at the time perhaps the leading artist in Amsterdam, it wasn’t his income that was most instrumental in the purchase. His wife Saskia (van Uylenburgh) came from a socially prominent family and this fact must have carried some weight with the lenders. Much of the initial house loan was never repaid and long after Saskia’s death in 1642 this extended debt, among others, led in part to Rembrandt’s bankruptcy (cessio bonorum) in 1656 and loss of the house (he was forced to move out in 1658). The forgiving phrase in Latin for bankruptcy used in the Dutch Republic, cessio bonorum or “stopping of the goods”, often generously extended the acceptable commercial euphemism on account of goods lost at sea, even to those like Rembrandt not engaged in capricious sea trade. Extenuating circumstances – including the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-54) over trade disputes involving Dutch shipping – during a protracted Dutch financial crisis in the 1650’s were also greatly responsible for Rembrandt’s bankruptcy, although it is well known Rembrandt generally lived beyond his means, even while married to Saskia and certainly beyond his own income once the capital of her money could not be touched; he could only use the interest in the legal Dutch terms of usufruct that her family contracted.

But the house is largely now as in Rembrandt’s time, filled with his art and that of contemporaries in a superb collection, including his own engravings and etchings (over 250 out of nearly 300 total) as well as some of his paintings and an large graphics collection of engravings and drawings by other masters. Other works are by his teacher Pieter Lastman and some of the Rembrandthuis art collection is on permanent loan with exhibitions that rival many larger museums. Additionally, the rooms of house now greatly reflect his work and life with quotidian objects of the seventeenth century after the 1999 restoration. The museum also serves as the venue for active public workshops, lectures and related functions and has excellent educational facilities. Practical expert demonstrations in the methods and steps of etching and pigment preparation are offered daily, both of which this author has attended.

Several of the rooms have been refurbished with typical furnishings, and some even have built-in features which may have belonged to the artist. The “cabinet de curiosite” upstairs on a higher museum floor has a reconstructed natural history collection much like Rembrandt’s own, since he was famous for buying exotic objects at auctions.

Rembrandt’s collection of busts, including Classical authors, was also useful. For example, he painted Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer in 1653 for the noted Sicilian collector Antonio Ruffo, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A nice touch in this painting is the gold chain hanging loosely from Aristotle’s neck with a medallion of Alexander the Great, both his pupil and lord. In keeping with his intelligence, Rembrandt had an insatiable curiosity extending far beyond the use of exotic objects as props. A copy of this famous Homer bust – well known from many ancient examples – can also be seen on the shelf above the box bed in a photo below taken by the author in 2012.

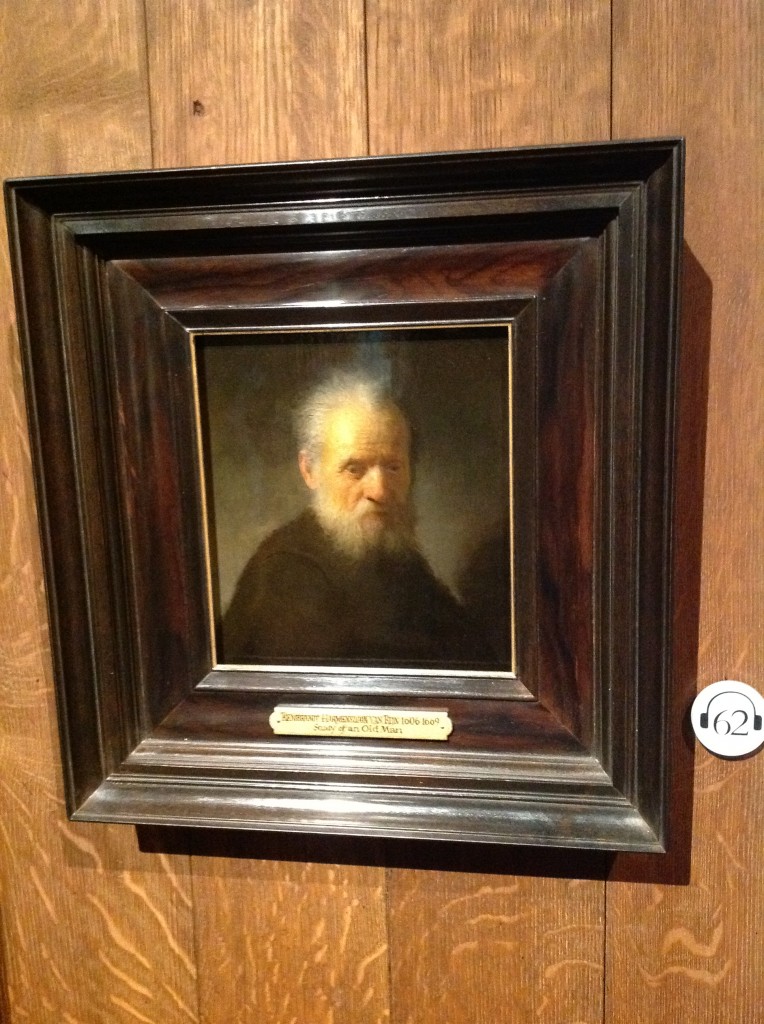

A highlight of the current 2012 exhibition in the Rembrandthuis is a small portrait, Bearded Old Man now known to have been painted by Rembrandt around 1630. It was recently proven by XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence spectrometry) to be by the artist partly because it has an unfinished underpainting self-portrait of him. XRF research on Bearded Old Man was conducted by Professor Koen Janssens of University of Antwerp and Professor Joris Dik of Delft University of Technology. The painting was identified stylistically and on overall portrait quality as a Rembrandt by Ernst van de Wetering and suggested by him as having an underpainting in 2009. [8] The XRF analyses on this Rembrandt painting were undertaken at Grenoble’s European Synchrotron Radiation (ESRF) laboratory and the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) lab at Brookhaven National Laboratories (BNL) in New York, where Dr. Peter Siddons also assisted. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) as well as optical microscopy were also used on paint samples. More and more, such archaeometric instrumental analyses of art are increasingly facile tools for such cross-fertilized research combining art, archaeology and science.

Next time anyone is frayed by the understandably long lines at the world class Van Gogh Museum and the equally world class (but under renovation until 2013 and therefore diminished) Rijksmuseum, a visit here is a must. Note that Schiphol International Airport considerably outside Amsterdam also has a small extension art gallery from the Rijksmuseum to feed the weary traveler’s soul. The Museum Het Rembrandthuis – also world class – is worth every minute spent, a fruitful visit for anyone interested in contextualizing Rembrandt in his time and place. Even though so much has changed in Amsterdam around the modern Jodenbreestraat (although picturesque 17th c. canals are still only a stone’s throw away), the Rembrandthuis museum is keen on bridging from the 17th century to the 21st and serves an admirable role doing this and more for the inquisitive visitor, whether an academic professional or anyone loving Rembrandt’s peerless place in art and history.

Notes:

Note: the best source for current exhibitions and workshops and the best history of the Rembrandthuis itself is the Het Rembrandthuis Museum website: (http://www.rembrandthuis.nl/index.php?item=0&lang=en)

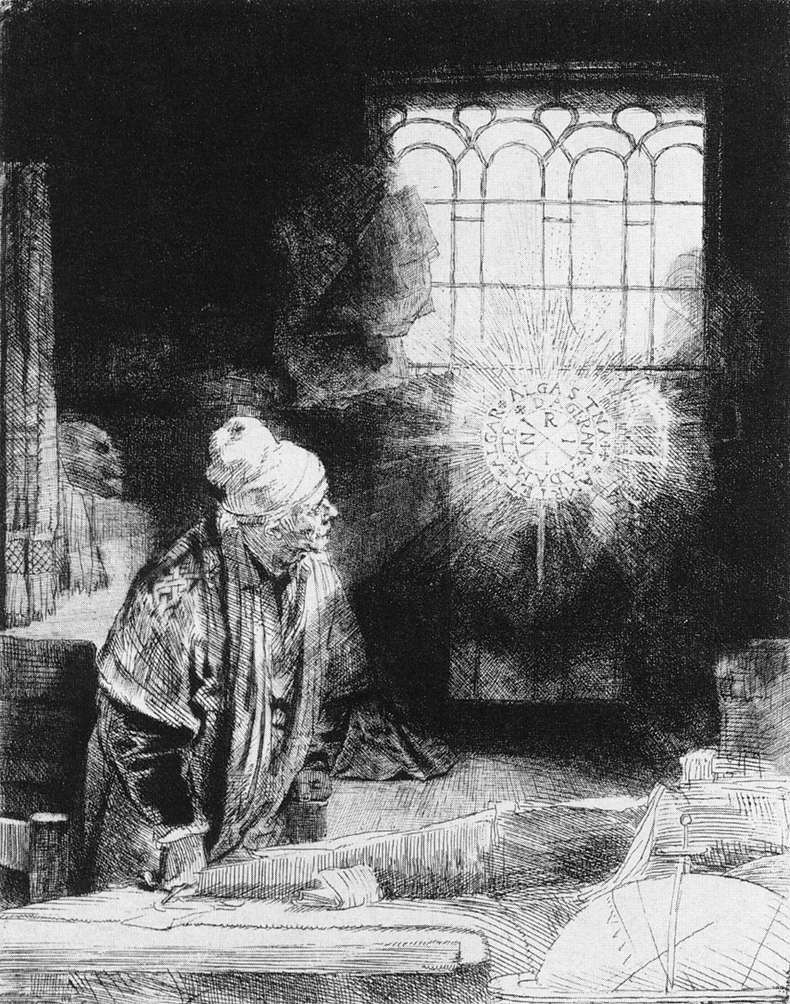

[1] (although Rembrandt mistakenly exchanged incorrect a “z” [zayin] for the correct terminal “n” [nun]). See Michael Zell. Reframing Rembrandt: Jews and the Christian Image of Seventeenth Century Amsterdam. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, espc. ch. 3, 58-98.

[2] possibly thus altered in 1661, only a few years after Rembrandt left it.

[3] While after Saskia’s untimely death in 1642, Hendrickje entered Rembrandt’s household at least by 1647, Geertje entered at least in late 1642 or early 1643 and was still around until at least 1649 for the infamous matrimonial court case where she accused Rembrandt of promising to marry her (the court fined Rembrandt but mostly dismissed Geertje’s case); in 1650 Rembrandt had Geertje placed in the Gouda Spinhuis for morally corrupt women (former prostitutes) and mentally unhinged women. Gary Schwartz (Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings, Viking, 1985; The Rembrandt Book, Harry Abrams, 2006) and Charles Mee (Rembrandt’s Portrait: A Biography, Simon & Schuster, 1988) have suggested the painting is a portrait of Geertje; Christopher White, however, (e.g. The Drawings of Rembrandt, British Museum, 1962; Rembrandt as an Etcher, A Study of the Artist at Work, 2nd ed., Yale, 1999) has suggested it is Hendrickje.

[4] This painting in the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, is now titled A Woman in Bed. But the National Gallery of Scotland also suggests it is Sarah from Tobit based on a similar precedent painting by Pieter Lastman (Rembrandt’s teacher). It is thus also often titled Sarah, Bride [or Wife] of Tobias in Rembrandt literature.

[5] See “Tobit” or “Asmodeus” in Isidore Singer, ed. The Jewish Encyclopedia. Ktav Publishing, 1901 (1906 ed.).

[6] See CODART: Dutch and Flemish Art in Museums Worldwide. “Museum Boijmans van Beuningen’s Tobit and Anna: A new Rembrandt?” March 14, 2012 (http://www.codart.nl/news/791/).

[7] Patrick Hunt. Rembrandt: His Life in Art, 2nd. ed. New York: Ariel Books & San Diego: University Readers, 2007, 166-8.

[8] Leslie Schwartz (Museum Het Rembrandthuis). “X-rays Reveal an Unfinished self-portrait by Rembrandt van Rijn.” University of Antwerp Press Release. (http://www.rembrandt.ua.ac.be/). The portrait of the beard old man is dated around 1630 and the unfinished self-portrait of a beardless young man with beret and possible lace collar, like other self-portraits of the young Rembrandt about age 22 . It is stylistically dated (van der Wetering) from somewhere between 1628-30 near the end of his Leiden period when he was fast becoming one of the best portraitists in Europe. If anyone knows the young Rembrandt self-portraits, it is Ernst van de Wetering, see his exposition catalog with Bernhard Schnackenburg, The Mystery of the Young Rembrandt, Kassel: Staatliche Museen Wolfratshausen & Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam, 2002.