By Patrick Hunt –

One of the most important marbles of Italy has almost become synonymous with the splendor of Venice, indeed this marble has itself traveled further than the outposts of Venice’s extensive empire. Such is the lure of Verona Marble. While it can be found in the most important contexts of Venice – prominently displayed, for example, in St. Mark’s Cathedral – it can also be found as far away from Italy as California, seen above in the Gardens of Filoli near Woodside, where it graces a weathered Renaissance fountain with faun heads from which water once spouted in double sprays either sides of the fauns’ mouths.

The city of Verona itself deserves far greater attention as one of Italy’s most beautiful cities. Situated in the Padana– the Po River Valley – from Celtic times onward centuries before Rome conquered the region, Verona became an important east, west, north, south junction between Lombardy and the Alps through the Brenner Pass connecting Italy to Austria along the Adige River Valley. Not only was Verona eventually an important Roman city with great monuments like its splendid amphitheater – the venue for one of the world’s most important summer outdoor lyric opera series – and a vital Ostrogoth metropolis in the sixth century AD/CE when Rome was mostly in ruin, but later through its benevolent ruler Cangrande I, Verona also provided Dante a safe harbor during his permanent exile from Florence between 1312-18. Verona’s medieval bridges are also engineering feats, like the Ponte Scaligero finished in 1356, at the time the medieval world’s greatest double arched bridge at 49 meters.

Most literary people remember Verona because Shakespeare immortalized it as the city of the Montagues and Capulets in Romeo and Juliet. Perhaps the bloody feuds between the Montagues and Capulets symbolically figure in the reddish marble patterns of Verona marble and a sophisticated Shakespeare would have known this marble color through his contacts with Tudor stately homes where it graced expensive pavements. When Shakespeare describes blood spreading on Verona’s pavements, its spattered marble hue is already an apropos foreshadowing. As Act III, Scene I warns, “For now, these hot days, the mad blood is stirring.” In Scene V, Romeo mourns that his “reputation is stained” by Mercutio’s death and after Tybalt’s like fall, Lady Capulet also cries out, “O, the blood is spilt”. All this illicit dueling is summed up by the Prince of Verona as a “bloody fray.” Looking at Verona Marble in this Shakespearian context may be a deliberate poetic figure apropos for a dramatically colored stone.

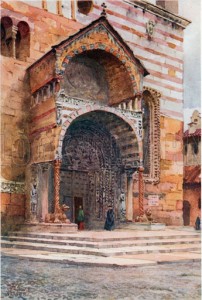

British Victorian artist and critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) praised Verona as his favorite city in Italy; his correspondence with friends frequently admonished them that if they only visited Florence and Siena in Tuscany and Venice in the Adriatic without seeing Verona that they were greatly losing out. Ruskin was enough of an arbiter of 19th century British aesthetic taste that there is even an Oxford University art school named after him. Ruskin’s meticulous watercolors of the sculpted griffins and lions of Verona Cathedral show some of the pride of Verona over its distinctive reddish marble. Ruskin’s superb watercolor collection in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, which this author tries to view every year, rival those of the German Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer.

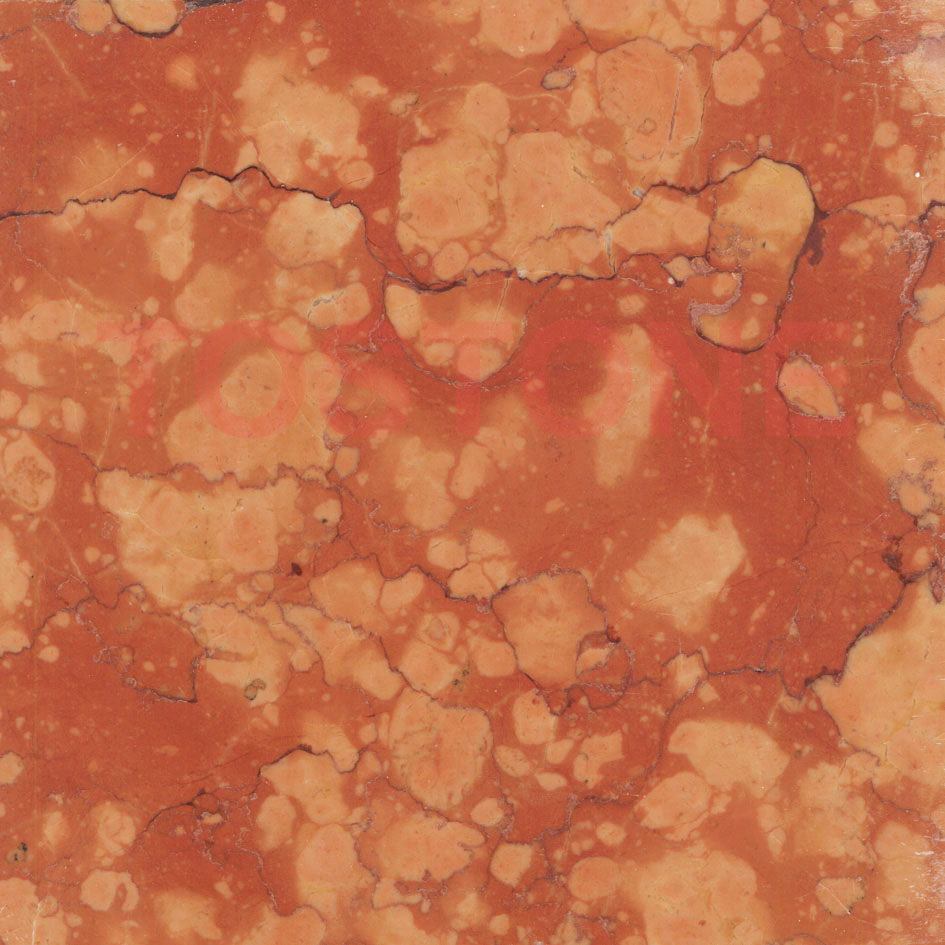

Geologically, Verona Marble – often called Rosso di Verona – should technically be considered a Jurassic red nodular limestone because it is usually found as a sedimentary to low-grade metamorphic stone. To medieval and later scalpellini (stonecutters”) and to the Romans it would have been marmor. [1] The traditions of using this stone possibly go back to at least Late Roman Verona [2] and possibly Rimini (ancient Ariminum), [3] and certainly medieval Venice.[4] Monica Price, who has studied the scalpellini guilds, is the curator of the Oxford University Corsi Collection and has written the best source book on such stone. [5]

Its distinctive color patterns range from creamy white to beige in its lesser grades and in its highest grade (most expensive), its orange nodules are set within a reddish matrix. Verona Marble is also geologically similar to other local breccias or conglomerate rocks in northern Italy. As this rock formed in the Jurassic, lighter-hued fragments floated in solidifying darker muds. Sometimes Verona Marble even mixes veins of white between the orange and red nodules, seen in Jacopo Bassano’s (1510-92) unique Adoration of the Magi painted on a dish of dramatic Verona Marble layered over slate, circa 1565 and now in the Loyola University of Chicago Collection. Its range of hues still make it dramatic and expensive to import abroad, and in original contexts like the Cathedral of Verona, Verona marble is the perfect medium for the breathtaking lions and griffins of the protiro porch where the backs of the guardian griffins and lions support spiraled Byzantine style columns from their backs. Verona Marble’s legacy is a rich one, making it a marble of choice not only in Italy but also wherever highly-colored marble has been prized.

Notes:

[1] See Oxford’s Corsi Collection Catalog, Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Samples 70 & 497.

[2] Gabriele Borghini, ed. Marmi Antichi. Rome: Edizione de Luca, 1997, 49, S. Ambrogio di Valpolicella. Also see – dated but still useful – Pirro Marconi. Verona Romana. Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’arti grafiche, Scaliger Society, Verona,1938.

[3] In 1999 the Soprintendenza of Emilia-Romagna and its archaeological office recovered some patrimonial objects from the Covignano Hills (roughly west of Rimini) including a putative Rosso di Verona Roman basin, now in Rimini’s Museum since 2008. Archive of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna, Bologna (http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/sito-MiBAC/Contenuti/MibacUnif/Comunicati/visualizza_asset.html_1630312543.html).

[4] Marco Frascari. “The Lume Matriale in the Architecture of Venice.” Perspecta 24 (1988) 136-45, Yale University School of Architecture, esp. 143 in the Ca’ Dario.

[5] Monica T. Price. The Sourcebook of Decorative Stone: An Illustrated Identification Guide. Firefly Books, 2007, 14 ff.