By Patrick Hunt

Along with his many other sometimes astonishing accomplishments ranging through history and archaeology to science and literature, polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) was crucial to the reception of Europe, especially Germany, for its reappraisal of classical antiquity. His 1786-87 itinerary as distilled from correspondence in Italian Journey (Italienische Reise) published circa 1817 became a magnet for subsequent travelers. This brief article explores both the apotheotic underpinnings of the nineteenth century “Goethe cult” (also known as the “Goethe myth”) and the above Tischbein painting, as also explored elsewhere. [1] This painting “remains the most persistent image of Goethe”. [2]

While he drew from Lessing’s 1774 Laocöon along with the geometric studies of Antonio Palladio and the art history of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Goethe formed his own opinions and contributed seminal ideas to European understanding as he moved from Bolzano, Verona, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Rome, Naples and Sicily through the mixed landscapes of past and contemporary Italy, topographies he sought to connect intellectually like few before him.

Visiting Sicily, his visionary statement that “Sicily is the key to Italy” is prescient given that this island has long been the cornerstone of Mediterranean expansion from Phoenician to Greek through Punic, Roman, Byzantine, Norman and even Baroque layered culture. Nearly every year I sit transfixed on the very spot in the Greco-Roman theater of Taormina where Goethe romantically pronounced this the “best view” in the world with a smoking Mt. Etna and the curving bay of Giardino Naxos and the Ionian Sea seen through the ruined theater arcade.

The famous 1786 iconic portrait Goethe in the Roman Campagna by Johann Tischbein both initiates and celebrates Goethe’s international status as one of the prime movers in not only German circles but Europe’s as well as the fascination of the world centered around the Bourbon court of Naples in the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum that also drew antiquarians like William Hamilton and the like. Goethe’s broad-brimmed gray hat tilts up to keep his three-quarter view face looking right in full light and a traveling mantle is thrown over his burnt orange coat and white cravat, one pant pants leg with only a half-breech white stocking leg ends in gray shoes. At age 37, he reclines across several worked blocks of Roman stone under partly cloudy skies. Some of the dressed stones have been fully worked with traces of anathyrosis on finely trimmed edges.

Bisanz suggests the leaning figural style of Goethe approximates (and may allude to) the Parthenon Phidian sculpture group of the “Three Goddesses” on the right side of the east pediment, where the lower goddess faces the same way as Goethe [3]; equally possible on the same pediment sculpture but on the left side, Goethe’s position appears to also resemble the left solo figure (although in the opposite direction as Goethe is posed) – scholars like Cook suggest this latter figure is either Dionysus or Herakles depending on whether he is seated on a panther or lion skin because of the feline paw dangling underneath [4] – as the pedimental angel slopes down to the rising chariot figures. One problem with these Parthenon identifications is that the Parthenon sculpture would still have been in Athens until Elgin’ s forays there around 1802; on the other hand, Jacque Carrey had sketched the pedimental sculptures in 1674 and Dalton had sketched them in 1749, [5] among others like Stuart in 1750 prior to Tischbein’s canvas.

Although Goethe and Tischbein soon parted ways, the figure of Goethe dominates the Roman Campagna countryside. While the date the canvas was completed is often debated, generally accepted as being finished in Naples in 1786 unseen by Goethe, many have linked the artistic subjects in the painting to known objects and other “landmarks” Tischbein almost cravenly quotes as likely referencing Goethe’s own Classical fascinations on his Italian journey.

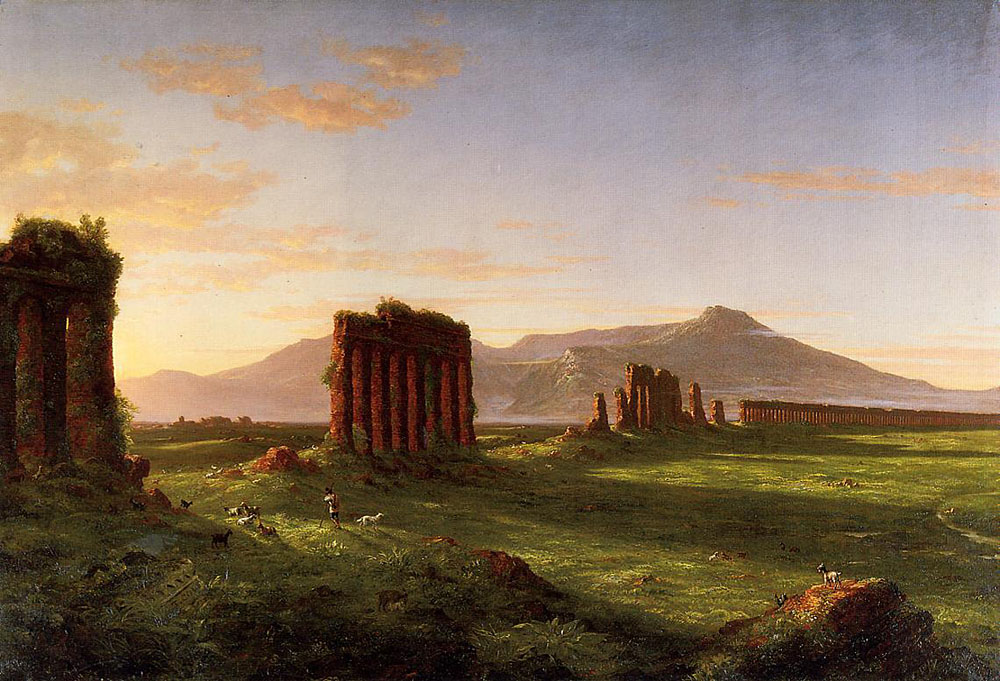

For example, in the mid-distance facing the Alban Hills where pre-Roman history remembered Alba Longa and Nemi, there are fairly clear representations of the region of the Via Appia Antica with the Roman turreted tomb of Caecilia Metellus conflated with the broken arcades of aqueducts like those of the Claudian Aqueduct also later painted by Corot, and Cole, among others. Long before Tischbein painted this similar landscape scene, the Antwerp painter Paul Bril (1554-1626) rendered under a dark sky his Capriccio of the Via Appia Antica, Near Rome, with the Tomb of Cecelia Metella and the Claudian Aqueduct, circa 1617. [6]

Perhaps far more important in the literary sense, the slightly tilted sculptural frieze group fragment immediately behind Goethe’s outstretched legs is generally recognized as a visual reference to Goethe’s own literary take on Euripides in Goethe’s Iphigenia auf Tauris (1786 in verse), which he was then rewriting in Italy. While sculpted friezes of this Euripidian story can be found in Naples from the extant Bourbon excavations at Pompeii and in the Neapolitan Campania – other friezes of Orestes and Pylades were originally noted in Rome at the Villa Albani [7]. Prior artists had also painted versions of this story along with operatic renditions like Gluck’s 1779 Iphigénie en Tauride (which Goethe must have known) in similar terms as Tischbein’s “antique relief” version with Electra receiving Orestes and Pylades, including Benjamin West in his 1766 Pylades and Orestes Brought as Victims Before Iphigenia. In most variants of this story originally from Euripides, after killing his mother Clytemnestra for murdering her husband over Iphigenia’s “death”, Orestes had fled to Delphi and misinterpreted the Delphic oracle who commanded him to “bring the sister”. Thinking his sister was dead – a sacrificial victim to Artemis (Diana) by their father Agamemnon – Orestes went to Tauris with his friend Pylades to steal a golden (wood in Euripides) statue of the goddess thinking this would fulfill the oracle’s demand. Instead they were caught and condemned to die. While each tried to save the other, Orestes was to be sacrificed for impiety – another Atreid dynasty peripety – but was recognized by his still-living priestess sister Electra and saved by her.

Lastman’s crowded painting highlights the moment before Iphigenia arrives to recognizes her brother clad in white when both young men are trying to prevent the other’s sacrifice and Orestes nobly demands he become the sacrifice on the prepared altar whose finishing touches await his sister priestess. West’s image has them brought to Iphigenia without the dramatic tension, only the shame of impiety and the salvific recognition scene instead. Goethe’s own Iphigenia auf Tauris story adapts his interpretation to his own age in a different reading than Euripides, reflecting his unique philosophical and literary imagination.

Tischbein is no doubt referring to Goethe’s telling of the story in the marble relief he has painted, perhaps even suggesting the “archaeologist” Goethe had “unburied” the story itself from Classical antecedents – much like Pompeii’s antiquities at the same time were being unburied, although not precisely excavated in the modern sense – in this imaginary yet real landscape. Goethe’s antiquarian interests were contemporary with this birth of archaeology at Pompeii and Herculaneum although the discipline as we know it was still in the future – perhaps Goethe can see it in the distance in Tischbein’s painting – since archaeology was only then transitioning from philology to art and historical context. Like the historian Polybius long before him, Goethe certainly needed his own Italian journey to better fathom the past in its topographical context. Likely influenced by the subject of Goethe’s interest but without his direct presence (however indirect his literary presence), later painters enlarged on the Roman Campagna, possibly alluding to Tischbein. Thomas Cole’s painting, far more dramatic than Tischbein’s where the drama is a godlike Goethe himself, envisions the same Roman countryside not as a Classical landscape but as a Romantic one with its oblique evening light – reminiscing Rome’s cultural sunset – and long shadows of the ruined aqueduct. Goethe may cast no shadow in Tischbein’s canvas, but his literary and artistic shadow over Classical reception and even the Romanticizing thereof is nonetheless impossible to escape.

Notes:

[1] Rudolf Bisanz. “The Birth of a Myth: Tischebin’s Goethe in the Roman Campagna”. Monatshefte 80.2 (1988) 187-99.

[2] Gretchen Hachmeister. Italy in the German Literary Imagination: Goethe’s Italian Journey and its Reception by Eichendorff, Platen and Heine. Camden House, 2002, 13.

[3] Bisanz, 190; he may include the male reclining figure here although it is ambiguous.

[4] B. F. Cook. The Elgin Marbles. London: British Museum Press, 1993, 6th imp, 49.

[5] Cook, 46, 58

[6] note it was recently sold privately at Christie’s London as Lot # 205 for £ 46,850 in July 2011.

[7] Octavian Blewitt. A Handbook for Travelers in Central Italy, including the Papal States, Rome and Etruria. London: John Murray, 1850, 2nd ed., 534